File: <scrubtyphus.htm> <Medical

Index> <General Index> Site Description Glossary <Navigate

to Home>

|

SCRUB TYPHUS (Contact) Please CLICK on

Image & underlined links for details:

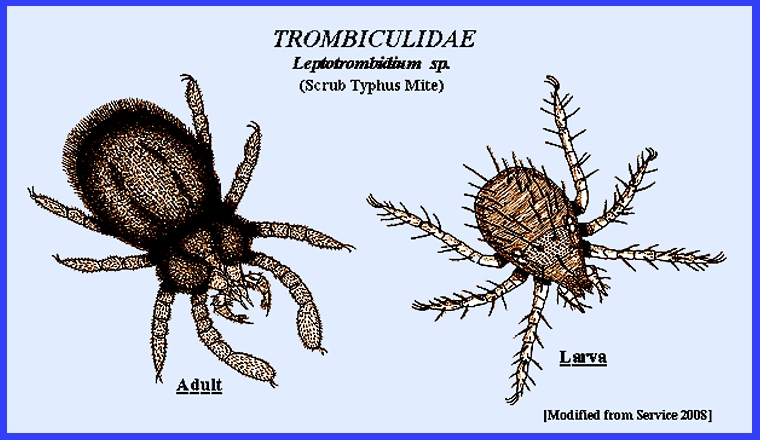

LIFE CYCLE (See Diagram) Trombiculid mites have a complex life cycle and different

terms have been applied to the developmental stages, but the terminology used

by Service (2008) is applied as follows:

Adults of this group are not parasitic but rather inhabit the soil

where they feed on other arthropods.

During warm weather a female mite may lay up to five eggs daily on

organic material located on the soil surface, in field grasses, etc. "Deutorum" larvae with six legs

emerge but initially do not leave the egg shell (the

"Deutovum"). Activity

begins about a week later when the mites swarm all over the soil and

grasses. They try to attach to

mammals and birds as well as to people with which they come into

contact. They gather around soft and

moist areas of a host. The larvae then penetrate into the skin, injecting saliva

that destroys cells. They feed on

lymphal fluid instead of blood. The continued

release of saliva then results a nasty skin reaction. Some species spend a whole month on a

host, but the vectors of Scrub Typhus remain on a host for only

about a week. When fully fed the

larvae exit the host and drop to the ground where they bury into the soil or

under leaf litter, etc. There they change

into a "Protonymph," which moults within week and gives rise to a

"Deutonymph" with eight legs.

The deutonymphs like the adults feed for a couple of weeks on

arthropods in the soil. Feeding stops

and the nymphs change into a "tritonymph" that moults after about

two weeks giving rise to the adult stage.

The total life cycle generally takes up to two months, but sometimes

8-10 months are required. Because nymphs and adults feed on other arthropods they

require habitats where there are sufficient arthropods present to sustain

them. Service (2008) noted that ideal

habitats are often produced when vegetation is cleared for agriculture or

wood products. A larva will remain on only one host during its lifetime,

so transmission does not occur between people by them. Rather the nymphs and adult mites are

vectors. Transovarial transmission among

mites insures virus persistence in their population (See Service 2008 for details

about transmission). CONTROL Repellents have been recommended for control, as it is

difficult to effectively attack the mites.

Once principal habitats among the vegetation are discovered these can be

sprayed with insecticides or even destroyed by burning. = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

= = Key References: <medvet.ref.htm> <Hexapoda> Azad, A. F. 1986. Mites

of public health importance and their control. WHO/VBC/86.931. Geneva, Switzerland Frances, S. P., D. Watcharapichat, D. Phulsuksombati

& P. Tanskul. 2000. Transmission of Orientia tsutsugamushi, the aetiological agent for scrub typhus, to co-feeding

mites. Parasitology 120: 601-607. Hengbin, G., C. Min, T.

Kaihua & T. Jiaqi. 2006. The foci of scrub typhus and strategies of

prevention in the spring in :ingtan Island, Fujian Province. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 1078: 188-196. Kawamura, A., H. Tanaka & A. Tamura

(eds.). 1996. Tsutsugamushi Disease: an Overview. Tokyo Univ. Press. Matheson, R. 1950. Medical Entomology. Comstock Publ. Co, Inc. 610 p. Ogawa, M., T. Hagiwara, T. Kishimoto et al. 2002. Scrub typhus in Japan: epidemiology and clinical features of

cases reported in 1998. Amer. J. Trop. Med. & Hyg. 67: 162-65. Roberts, S. H. &

J. H. Zimmerman. 1980. Chigger mites: efficacy of control with two pyrethroids. J. Econ. Ent. 73: 811-812. Sasa, M. 1961.

Biology of chiggers. Ann. Rev.

Ent. 6: 221-244. Service, M. 2008.

Medical Entomology For Students.

Cambridge Univ. Press. 289 p Strickman, D.

2001. Scrub typhus. IN:

The Encyclopedia of Arthropod-Transmitted Infections of Man and

Domesticated Animals. CABI, Wallingford, pp. 456-62 Takahashi, M., M. Misumi, H. Urakami et

al. 2004. Mite vectors (Acari: Trombiculidae) of

scrub typhus in the new endemic area in northern Kyoto,

Japan. J. Med. Ent. 41: 107-114. Takahashi, M., M. Murata, H. Misumi, E. Hori, A. Kawamura. & H. Tanaka. 1994.

Failed vertical transmission of Rickettsia

tsutsugamushi

(Rickettsiales: Rickettsiaceae) acquired from rickettsemic mice by

Leptotrombidium pallidum (Acari: Trombiculidae). J. Med. Ent. 31: 212-16. Traub, R. & C.

L. Wissemann. 1968. Ecological considerations in scrub typhus.

1> Emerging concepts. Bull. WHO

39: 209-218. Traub, R. & C. L.

Wissemann. 1974. The ecology of chigger-borne

ricksettsiosis (scrub-typhus). J.

Med. Ent. 11: 237-303. Walter, D. E. & H.

C. Proctor. 1999. Mites: Ecology, Evolution &

Behavior. Univ. of New South Wales

Press, Sydney. |