File: <relapsingfever.htm> <Medical

Index> <General Index> Site Description Glossary <Navigate

to Home>

|

RELAPSING FEVER DISEASE (Contact) Please

CLICK on underlined links for details:

Symptoms include repeated bouts of fever, which last from

3-5 days. Apyrexia varies from 5-10

days.

Table 1. Distinction

Between Hard & Soft Ticks (Derived from Service 2008)

Chung & Feng (1936)

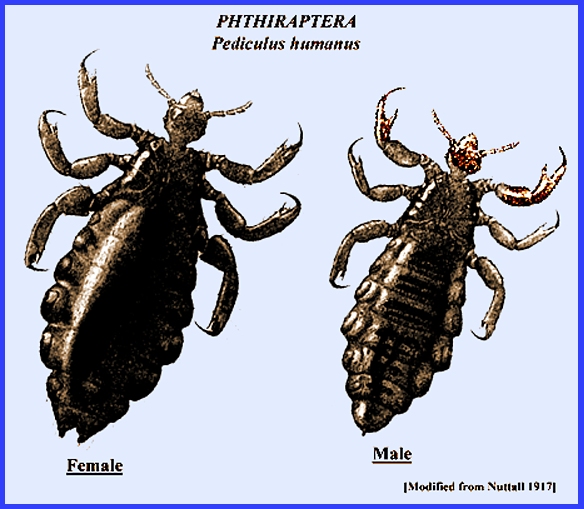

studying the disease life cycle in both body and head lice found that the

vector obtains the spirochetes while drawing blood from a host. Most of the spirochetes are then digested

and vanish after 6-8 hours. However,

several manage to penetrate the intestinal wall and reach the coelomic fluid

in about two hours. The spirochetes

then multiply in the body cavity by transverse division and distribute to all

parts of the body. They do not invade

the tissues nor are they transmitted through the egg or feces. They will remain in the louse for its

entire life of about 20 days. Humans

are infected when the lice are crushed on the skin near abrasions. There have been epidemics of relapsing fever worldwide,

and it is always associated with either lice or ticks. Matheson (1950) details the areas and

severity where epidemics have occurred over many years. Mortality rates have

sometimes killed large numbers of people as s in West Africa where 80,000

died during a two-year epidemic. Table 2. Occurrence of

Relasping Fever (Derived from Matheson 1950)

CONTROL Control of louse populations is effective in eliminating

the disease. Avoiding tick habitats

and the diseases they carry is about the best way to avoid bites and infection. Traditionally various dips and sprays have

been used for domestic animals. There

are also vaccinations available for some diseases, and consulting a physician

is advised for the latest treatments. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

= = Key References: <medvet.ref.htm> <Hexapoda> Bates, L. B., L. H. Dunn

& J. H. St. John. 1921. Relapsing fever in Panama. Amer. J. Trop. Med. 1: 183-210. Bowman, A. S. & P.

A. Nuttall (eds.). 2004. Ticks: biology, disease and control. Parasitology 129 (Suppl.): S1--S450. Chung, H. & L.

C. Feng. 1936. Studies on the development of Spirochaeta recurrentis in body

louse. China Med. J.. 50: 1181-84. Cunha, B. A. (ed.). 2001. Tickborne Infectious Diseases: Diagnosis

& Management. Marcel Dekker, NY & Basel. Davis, G. E.

1939. Ornithodoros parkeri; distribution and

host data; spontaneous infection with relapsing fever spirochetes. U. S. Publ Hlth.

Repts. 54: 1345-1349. Davis, G. E. 1943.

Relapsing fever: the tick, Ornithodoros

turicata as a spirochaetal reservoir. U. S. Pub. Hlth. Repts. 58:

839-842. Francis, E.

1942. The longevity of fasting

and non-fasting Ornithodoros turicata

and the survival of Spirochaeta obermeieri

within them. IN: Symposium on relapsing fever in

the Americas. Amer. Assoc. Adv. Sci.,

Pub. 18: 85-88. Goodman, J. L., D. T.

Dennis & D. E. Sonenshine.

2005. Tick-Borne Diseases of

Humans. ASM Press, Washington DC. Klompen, J. S. H., W. C.

Black, J. E. Kelrans & J. Oliver 2nd.

1996. Evolution of ticks. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 41:

141-161. Krantz, G. W. 1978. A Manual of Acarology, 2nd edn. Oregon St. Univ., Corvallis. Lawrie, C. H., N. Y. Uzcategui, E. A. Gould & P.

A. Nuttall. 2004. Ixodid and argasid tick species and West

Nile virus. Emerging Infectious Diseases 10: 653-657. Mackie, F. P. 1907. The part played by Pediculis corporis in the transmission

of relapsing fever. British Med. J.

2: 1706-09. Matheson, R. 1950. Medical Entomology. Comstock Publ. Co, Inc. 610 p. Mazzotti, L.

1943. Transmission experiments

with Spirochaeta turicata and S. venezuelensis with four species of Ornithodoros. Amer. J. Hyg. 38: 203-206. McCall, P. J.

2001. Tick-borne relapsing fever. IN:

The Encyclopedia of Arthropod-transmitted Infections of Man and

Domesticated Animals. ed. M. W. Service,

Wallingford: CABI, pp 513-516. McDaniel, B. 1979.

How to Know the Mites & Ticks.

W. C. Brown, Dubuque, Iowa. Obenchain, F. D. & R.

Galun. 1982. Physiology of Ticks. Pergamon Press, Oxford. Sauer, J. R. & J. A.

Hair. 1986. Morphology, Physiology & Behavioral Ecology of Ticks. Ellis Horwood, Chicester; Wiley, New York. Schuster, R. & P W.

Murphy. (eds.). 1991.

The Acari: Reproduction,

Development & Life History Strategies.

Chapman & Hall, London. Service, M. 2008.

Medical Entomology For Students.

Cambridge Univ. Press. 289 p. Sonnenshine, D.

E. 1991. Biology of Ticks, Vol. 1. Oxford Univ. Press, New York & Oxford. Sonnenshine, D.

F. 1993. Biology of Ticks, Vol. 2. Oxford Univ. Press, New York & Oxford. Weller, B. & G. M. Graham. 1930. Relapsing fever in central Texas. J. Amer. Med. Assoc. 95: 1834-35. |