File:

<pthirapteramed.htm> <Medical Index> <General Index> Site Description Glossary <Navigate to Home>

|

Arthropoda: Insecta PHTHIRAPTERA Old = ANOPLURA (Sucking Lice) (Contact) Please CLICK on underlined links to view images To Search for Subject

Matter use Ctrl/F [Also

see: Phthiraptera Key] .

The mouthparts are

adapted for piercing and sucking blood.

The biting lice, Mallophaga, that are not of great

medical importance to humans, have chewing mouthparts that feed on scales,

feathers, and skin waste (Matheson 1950). Sucking lice are all permanent

ectoparasites of mammals. They have

highly modified mouthparts, which

when at rest are pulled back within a diverticulum that opens into the lower

part of the pharynx at its anterior end.

The thoracic segments are fused save for the genus Haematomysus. The tarsi have only one segment and end in

a single claw that is adapted for grasping and clinging to hair. Eggs are attached to the host's hair (Fig. 4). LIFE CYCLE Both male and female lice suck blood

during days and nights from their hosts.

They spend their entire lifetime on their hosts and in the case of

humans on clothing as well. The eggs,

which have been called "nits", are white and 1 mm. or less

long. The eggs hatch in 5-11 days if

located on the body. If warm hatching

conditions are not available, the eggs may survive more than a month. There is a hemimetabolous life cycle in

which nymphs resembling small adults hatch.

The nymphs can suck blood and pass three stages, which take about two

weeks. Nymphs that have left the body

for clothing require a longer time to complete their development. Service (2008) noted that lice deprived of

a blood meal couldn't live more than four days, whereas those that are able

to take 3-5 blood meals daily can live for about a month. Those hosts with a fever of about 40 deg.

Centigrade are not suitable for louse survival. Usually there are less than 100 lice

on a single person, but some people may harbor an infestation of up to 500

lice on their bodies and clothing.

Service (2008) even refers to an exceptionally high infestation of

20,000 lice being recorded! MEDICAL IMPORTANCE All

Phthiraptera are bloodsucking ectoparasites of mammals, and among the four

families only the Pediculidae have species that are of medical importance to

humans. Humans develop a rash from the salivary secretions. Pediculus

humanus, the body louse is associated with the spread

of many diseases, such as Ricketts,

Typhus and Relapsing Fever. This insect also

transmitted the disease known as Trench

Fever, which reduced Napoleon's Army and was prevalent in all war

areas during World War I (see ent79): The group

as a whole includes the most important vectors of Typhus Fever. During

World War II, DDT treatment of the Italian population was required to rid it

of a louse epidemic. Although the crab

louse is not a disease vector, it can be acquired either through

bodily contact or indirectly from bedding, etc. It is known to attack only humans and wild gorillas in Africa. DISTINGUISHING CHARACTERISTICS (Derived

from Service 2008) Pediculus humanus- Body Louse The adults are small brown or grey

and wingless, with a soft but tough integument. The males average 2-3 mm and females larger at 3-4 mm. Two black eyes are present and short

antennae with 5 segments. The thorax

consists of three fused segments and the legs are proportionately large and

well developed. There is a short spur

on the tibia that also bears a tiny spine.

The legs are all very close in size. The mouthparts are distinctive

because there is no extended proboscis but rather a sucking snout that projects

into the haustellum. This bears tiny

teeth that are able to grip the skin.

The stylets pierce the skin and saliva is injected to the wound to

deter clotting while the blood is sucked out to where it enters the stomach. The darkened sides of the abdomen are

sclerotized. Males have dark bands on

the abdominal dorsum and the posterior is round, which contrasts with females

where it is forked, which aids in holding fast during oviposition. Both sexes draw blood at any time

during the day or night, and both adults and immatures pass their lives

entirely on humans that includes their clothing. The eggs, known as nits, are ovoid, white and about 1 mm. in

length. There are openings on the egg

that allow air to enter for breathing and for egg expansion at hatching. Females may live for 2-4 weeks during

which 150-300 eggs can be laid. Some

humans may actually sustain as many as 500 lice on their body and clothing. Pediculus capitis - Head Louse There are few morphological

differences between P. capitis

and P. humanus, but rather

their location on the body distinguish them.

The life cycles are also similar but the eggs of P. capitis are usually glued to single

hairs located on the head with hatching occurring within seven days. Most infestations do not exceed 20 lice on

a head, but there are exceptions.

Female lice generally lay about eight eggs per day with not more than

150 per lifetime, which is not more than two weeks. Eggs hatch in 5-10 days. Head lice can be of serious public

health concern all over the world.

Overcrowding contributes to the louse population size in any given

area. However, unlike body lice that

are vectors of typhus, head lice may only be minor vectors of a relapsing

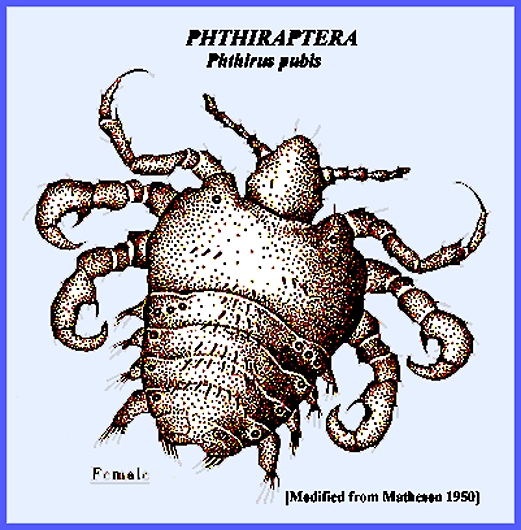

fever. Pthirus pubis - Pubic Louse Pubic lice are smaller than those in

the Pediculus genus, and their

bodies are almost completely round.

The legs also differ as the middle legs are thicker than the front

legs and they possess large claws, which gives them the common name of

"crab lice". Females lay

only about three eggs per day, totaling not more than 200 during their

lifetime. The eggs are a bit smaller

than the other two species, and their location is primarily in the pubic area

of humans, although other parts of the body are occasionally infested. Their activity is much less than the other

species. CONTROL Sucking lice rank number one in

livestock pests with three different species attacking cattle, two species

goats and one species hogs. Cleanliness is of the utmost importance in

keeping down infestations of sucking lice.

Because the eggs will not survive for more than a month infested

clothing not worn for over a month should be louse-free. For livestock it is important to maintain

the animals in a healthy state. Rotenone applied twice

a year in autumn and spring has been effective for the control of both adults

and eggs. = = = = = = = = = = = = Key

References: <medvet.ref.htm> <Hexapoda> Burgess, I. F.

1998. Head lice: developing a

practical approach. The Practitioner

242: 126-69. Burgess, I. F.

2004. Lice and their

control. Ann. Rev. Ent. 49: 457-81. Burgess,

I. F., C. M. Brown & P. N. Lee.

2005. Treatment of head louse

infestation with 4% dimeticone lotion:

randomised controlled

equivalence trial. BMJ 330:

1423-25. Buxton,

P. A. 1948. The Louse: An Account

of the Lice which Infest Man, Their Medical Importance & Control, 2nd

ed., Edward Arnold,

London. Chetwyn,

K. N. 1996. An overview of mass disinfestation procedures as a means to

prevent epidemic typhus. IN: Proc. 2nd Intern. Conf. on

Insect Pests in the Urban Environment. ICIPUE: pp 421-416. Matheson, R. 1950. Medical Entomology.

Comstock Publ. Co, Inc. 610 p. Service, M.

2008. Medical Entomology For

Students. Cambridge Univ. Press. 289 p Meinking, T., C. N.

Burkhart & C. G. Burkhart.

1999. Ectoparasitic diseases

in dermatology: reassessment of

scabies and pediculosis. Adv.

Dermatology 15: 77-108. Nuttall, G. H. G. 1917. The biology of Pediculus humanus. Parasitology 10: 80-185. Orkin, M. & H. I. Maibach (eds.). 1985.

Cutaneous Infestations & Insect Bites. Marcel Dekker, NY., Chapt. 19-26. Service,

M. W. (ed.). 2001. The Encyclopedia of Arthropod-transmitted

Infections of Man & Domesticated Animals. CABI: pp. 70-3, 170-4, 295- 9. Zinsser, H. 1935. Rats, lice

and history. Boston Globe. Zinsser, H. 1937. The rickettsia diseases: varieties, epidemiology and geographical

distribution. Amer. J. Hyg.

25: 430-63. |

FURTHER DETAIL = <Entomology>, <Insect Morphology>, <Identification Keys>