File: chagasdisease.htm> <Medical Index> <General Index> Site Description Glossary <Navigate

to Home>

|

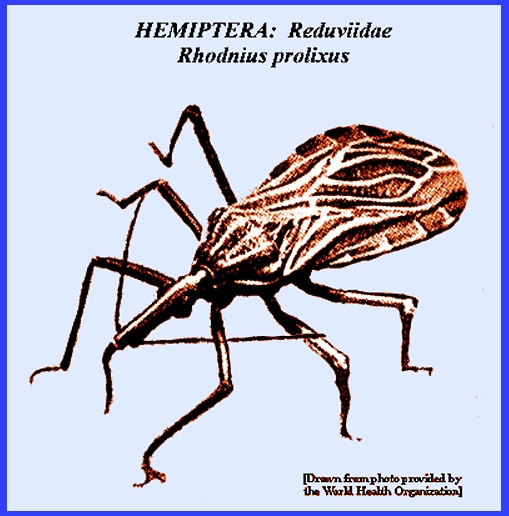

CHAGAS DISEASE (Contact) Please

CLICK on

image & underlined links for details: [See: Hemiptera

Key] LIFE CYCLE & BEHAVIOR In the

Hemimetabolous life cycle the eggs hatch after 10-15 days incubation to

produce small nymphs that resemble adults and which go through about five

stages of development. Like the

adults, the nymphs feed on blood, doing so mainly at night. They tend to seek out a host's head area for their blood meals. People are not normally aware that feeding

has occurred because there is little sensation. Detection of their presence is by observing cast molting skins

and streaks of fecal material in the houses.

The life cycle is quite long: about 3-10 months or sometimes even 1-2

years (Service 2008). All stages are

able to survive for several months without a blood meal. A large array of wild animals, including

squirrels mice, lizards and cattle, are attacked and may serve as reservoir

hosts. The vectors ingest the parasite's

trypomastigotes that reside in a host during a blood meal. The parasites then continue their

development within the insect's intestines.

There they further develop into epimastigotes and multiply to great numbers. Within 8 to 17 days these develop into

infective metacyclic trypomastigotes

in the lumen of the insect's posterior intestines. Vectors will regularly feed for 10-25 minutes or longer,

during which time many species of bugs excrete liquid or semi liquid feces

that may be contaminated with the metacyclic form of Trypanosoma cruzi that were derived from

an earlier blood meal. Infection in

humans occurs when bug excreta are scratched either into skin abrasions or

through the wound of the bug's bite, or when it might be rubbed into the eyes

or other mucous membranes.

Transmission results then only through the insect's feces and not

directly by its bite. Service

(2008) reported that there are some 70 species of Reduviidae that have been

found infected with T. cruzi,

but only about 12 species that live in close association with humans and feed

on them. Principal vector species are

Triatoma infestans

(southern South America), Pangastrongylus

megistus (southeastern Brazil), Rhodnius

prolixus (Honduras, Nicaragua, Colombia & Venezuela) and Triatoma dimidiata (Mexico

through northwestern South America).

The efficiency of a vector depends on how long it feeds on a human and

if it defecates during feeding.

However, Trypanosoma rangeli

that occurs from Mexico to Brazil and is transmitted by Rhodnius prolixus,

can infect humans directly by its bite. A further

discussion of the disease organism given by Service (2008) explained that Trypanosoma cruzi is really a parasite

of wild animals, such as opossums, armadillos and wild and urgan rats mice,

squirrels, monkeys, etc. that may serve as reservoir hosts. Simply eating the vectors or infected

animals can infect them. In some cases

humans can also aquire infection by eating infected meat or food that is contaminated

with infective bug excrement. The insect itself may also be an infection

reservoir, but in some areas humans are thought to be the main reservoir

hosts. Infection

rates in vector populations can frequently be very high. Service (2008) reported that it is common

to find infection rates of around 25 percent or higher. In California the Triatoma protracta

population can be 78 percent, but it rarely bites humans. Although vectors can account for more than

80 percent of transmission, blood transfusions account for 17 percent and

congenital transmission 2 percent. CONTROL Chagas

Disease is generally controlled by insecticide applications to the interior

surfaces of dwellings even though resistance to the insecticide develops

rapidly. Fumigation is effective but

must be done regularly. More

permanent but expensive control involves altering dwelling structures so as

to make them less attractive vector resting sites. Service (2008) noted that such alterations include plastering

walls to cover cracks and replacing thatched dwellings with those constructed

with bricks or concrete blocks, and having metal roofs. Because of the high rates of infection

among the human populations of northwestern South America, governments there

are launching massive efforts to inform and assist the public in vector

control. = = = = = = = = = = = =

= = = = = = = = Key References: <medvet.ref.htm> <Hexapoda> Barrett, T. V. 1991.

Advances in triatomine bug ecology in relation to Chagas disease. Advances in Disease Vector Research 8: 1843-76. Beard, C. R., C.

Cordon-Rosales & R. V. Durvasula.

2002. Bacterial symbionts and

their potential use in control of Chagas disease transmission. Ann. Rev. Ent.

47: 123-41. Brenner, R. R. &

A. M. Stoka. 1988. Chagas Disease Vectors I: Taxonomic,

Ecological & Epidemiological Aspects.

CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. Bryan, R. T., F.

Balderrama, R. J. Tonn & J. C. P. Dias.

1994. Community participation

in vector control: lessons from

Chagas disease. Amer. J. Trop. Medicine &

Hyg. 50: 61-71. Carcavallo, R. U., I. G.

Galfndez-Giron, J. Jurberg & H. Lent.

1999. Atlas of Chagas Disease

Vectors in the Americas, Vol. 3, Rio de Janeiro: Oswaldo Cruz Fundacion. Kingman, S. 1991.

South America declares war on Chagas disease. New Scientist (19 Oct) pp. 16-17. Lent, H. & P.

Wygodzinsky. 1979. Revision of the Triatominae (Hemiptera,

Reduviidae), and their significance as vectors of Chagas disease. Bull.Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist. 163:

123-520. Matheson, R. 1950. Medical Entomology. Comstock Publ. Co, Inc. 610 p. Moncayo, A. & M. I.

Ortiz-Yanine. 2006. An update on Chagas disease (human

trypanosomiasis). A.. Trop. Med.

& Parasit. 100: 663-77. Schofield, C. J. &

J. P. Dujardin. 1997. Chagas disease vector control in Central

America. Parasitology Today 13: 141-44. Service, M. 2008.

Medical Entomology For Students.

Cambridge Univ. Press. 289 p Legner, E. F. 1995. Biological control of Diptera of medical and veterinary

importance. J. Vector Ecology 20(1):

59_120. Legner, E. F. 2000.

Biological control of aquatic Diptera. p. 847_870.

Contributions to a Manual of Palaearctic Diptera, Vol. 1, Science Herald, Budapest. 978 p. Yamagata, Y. & J. Nakagawa. 2006. Control of Chagas disease.

Adv. in Parasitology 61:

129-65. |