File: <yellowfever.htm> <Medical Index> <General Index> Site Description Glossary <Navigate

to Home>

|

YELLOW FEVER DISEASE (Contact) Please

CLICK on

Image & underlined links for details:

Service

(2008) noted that in Africa simians of the genera Colobus, Cercopithecus

and Galago are primary

reservoir hosts, and that the virus circulates among these primates with

mosquito vectors such as Aedes africanus

that breed in tree holes. Matheson

(1950) provides a long list of monkey species that harbor the virus in

nature. Mosquito activity is highest

after sunset in the forest canopy when the hosts have settled down for the

night. The reservoir hosts show only

slight symptoms of the disease, it being rarely fatal. Imported exotic plants such as banana and

pineapple provide a new habitat for the disease to circulate as monkeys leave

the forest canopy to feed on their fruit.

In such places different species of Aedes

that are active during daytime vector the virus. Humans are more apt to be bitten in these forest peripheral

habitats, and subsequently by traveling about they can spread the disease to

other areas and in towns where different mosquitoes will serve as vectors,

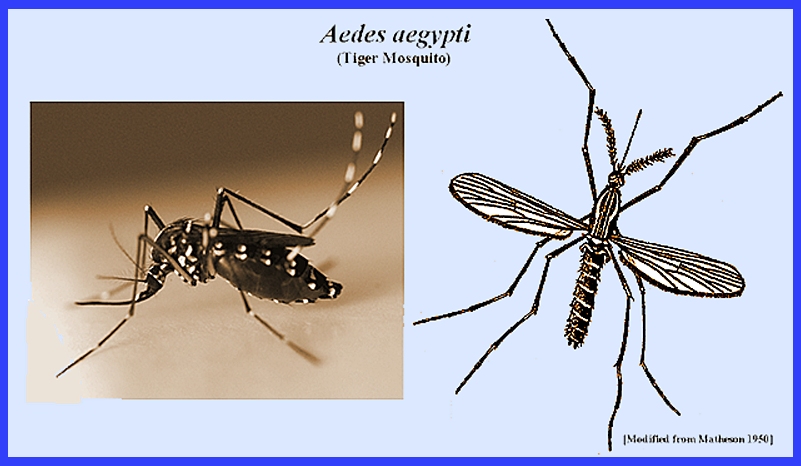

such as Aedes aegypti. Service (2008) thus distinguished the sylvatic from

the rural

cycle for the disease. There are

further complications with yellow fever transmission. For example, sometimes the virus may be

circulating among monkey populations but rarely reach humans because the

vector mosquitoes are not strongly attracted to them. The virus may also be transmitted

transovarial among the Aedes

species, which is more common in ticks.

There is also a venereal transmission when virus-infected male

mosquitoes pass the virus to female mosquitoes during mating. In the

Americas the yellow fever cycle is similar but differs in the kind of monkeys

serving as reservoir hosts (Matheson 1950 & Service 2008). The principal vectors are in the

forest-dwelling genus Haemagogus. Humans become affected in the forest

habitat and then carry the virus to surrounding areas where Aedes aegypti becomes the

principal vector species. Matheson

(1950) provides a list of 40 mosquito species that have been found capable of

transmitting the virus (See: Yellow

Fever Vectors). There are also

other blood sucking arthropods that in experiments have been found to

transmit yellow fever virus, including stable flies

and assassin bugs. There is an effective vaccine for yellow

fever, which is important to receive before traveling to areas where the

disease exists. Yellow Fever in Neotropics Cycle = = = = = = = = = = = =

= = = = = = = = Key References: <medvet.ref.htm> <Hexapoda> Barrett, A. D. T. &

S. Higgs. 2007. Yellow fever: a disease that has yet to be

conquered. Ann. Rev. Ent. 52: 209-29. Gratz, N. 2006.

Vector and Rodent-borne Diseases in Europe and North America. Cambridge Univ. Press, England Matheson, R. 1950. Medical Entomology. Comstock Publ. Co, Inc. 610 p. Service, M. 2008.

Medical Entomology For Students.

Cambridge Univ. Press. 289 p Legner, E. F. 1995.

Biological control of Diptera of medical and veterinary

importance. J. Vector Ecology 20(1):

59_120. Legner, E. F. 2000.

Biological control of aquatic Diptera. p. 847_870.

Contributions to a Manual of Palaearctic Diptera, Vol. 1, Sci. Herald,

Budapest. 978 p. Legner, E. F.. 2000. Biological control of aquatic Diptera. p. 847_870. Contributions to a Manual of Palaearctic Diptera, Vol. 1,

Science Herald, Budapest. 978 p. Monath, T. P.

2001. Yellow fever. IN:

Encyclopedia Arthropod Trans. Infections of Man & Domestic.

Animals. CABI, Wallingford. p.

571-77. Mutebi, J. P. & A. D. T. Barrett. 2002. The epidemiology of yellow fever in Africa. Microbes & Infections 4: 1459-68. Reeves, W. C. 1990. Epidemiology and

Control of Mosquito-Borne Arbovirusses in California, 1943-1987. Calif. Mosq. & Vect.

Contr. Assoc. Sacramento. |