File: <tularemia.htm> <Medical

Index> <General Index> Site Description Glossary <Navigate

to Home>

|

TULAREMIA DISEASE (Contact) Please CLICK on

image & underlined links for details:

There are many reservoir hosts including rodents, deer and

beavers, some bird species and carnivores.

But the principal reservoir host is the cottontail rabbit, Sylvilagus spp. Handling infected animals, both alive and

dead, may spread infection. Matheson

(1950) reported that the disease is highly infectious to humans and is

transmitted by various arthropods either by their bites, their crushed bodies

or their feces or by the tissues or body fluids of infected rodents. He also noted that it is occasionally water-borne

and infection can result from drinking or coming into contact with infected

water. Although many human infections

are traceable to contact with rabbits, certain tick species are of great

importance in maintaining the disease among the natural reservoirs (Matheson

1950). A number of hard tick species spread the disease. In Europe the main vectors are Ixodes ricinus

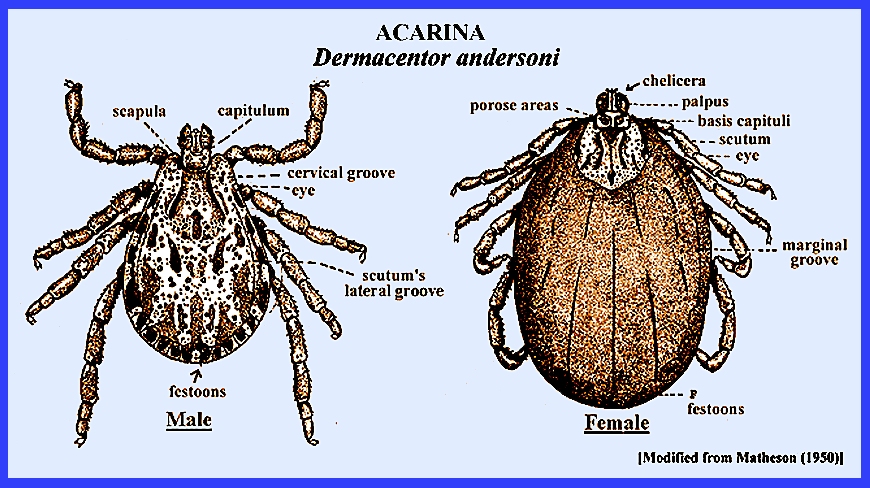

and Dermacentor spp. In North America various hard ticks and

other arthropods are vectors such as the tabanid fly, Chrysops

discalis. However in

North America of primary importance are the ticks Haemaphysalis

leporis-palustris, Dermacentor andersoni, D.

variabilis. Avoidance with contaminated sources is of the utmost

importance. When infections do occur

prompt medical attention is essential. = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

= Key References: <medvet.ref.htm> <Hexapoda> Burroughs, A. R. et al. 1945. A field study of latent

tularemia in rodents with a list of all known naturally infected

vertebrates. J. Infect. Dis. 76(2): 115-119. Camicas, J. L., J. . Hervy, F. Adam & P.

C. Morel. 1998. The ticks of the world (Acarida,

Ixodida): Nomenclature, Described

Stages, Hosts, Distribution. Paris:

Editions de l'ORSTOM. CDC.

2005. Tularemia transmitted by

insect bites. Wyoming 2001-2003 MMWK

Weekly 54(7): 170-3. Francis, E.

1929. Arthropods in the

transmission of tularemia. Trans. 4th

Internat. Cong. Entomol. 2: 929-944. Gammons, M. & G. Salam. 2002. Tick

removal. Amer. Fam. Physician

66: 643-45. Gothe, R., K. Kunze & H. Hoogstraal. 1979.

The mechanisms of pathogenicity in the tick paralyses. J. Med. Ent. 16: 357-69. Jellison, W. L. & R. R. Parker. 1945.

Rodents, rabbits and tularemia in North America. Amer. J. Trop. Med. 25: 349-362. Legner, E. F. 1995. Biological control of Diptera of medical

and veterinary importance. J. Vector

Ecology 20(1): 59_120. Legner, E. F. 2000.

Biological control of aquatic Diptera. p. 847_870.

Contributions to a Manual of Palaearctic Diptera, Vol.

1, Science Herald, Budapest. 978 p. Matheson, R. 1950.

Medical Entomology. Comstock

Publ. Co, Inc. 610 p. Needham, G. R. & P. D. Teel. 1991.

Off-host physiological ecology of ixodid ticks. Ann. Rev. Ent. 36: 313-52. Service, M.

2008. Medical Entomology For

Students. Cambridge Univ. Press. 289 p Sonenshine, D. E., R. S. Lane & W. L. Nicholson.

2002. Ticks (Ixodida). IN:

Medical & Veterinary Entomology, ed. G.

Mullen & L. Durden,

Ambsterdam Acad. Press. pp

517-58. Sonenshine, D. E. & T. N. Mather (eds.) 1994.

Ecological Dynamics of Tick-Borne Zoonoses. Oxford Univ. Press, New York. |