File: <trombidoidea.htm> <Medical

Index> <General Index> Site Description Glossary <Navigate to Home>

|

TROMBIDOIDEA (Chiggers) (Contact) Please

CLICK on

Image & underlined links to view:

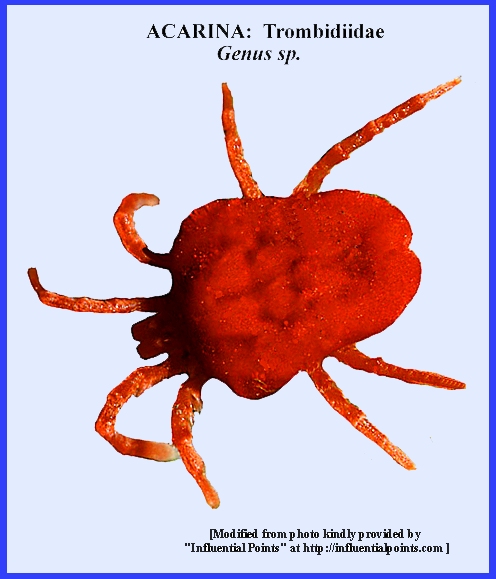

Although there are a

number of families, only one, the Trombidiidae, is of medical importance

because the larvae are parasitic on humans and animals. Other families do have parasitic species,

which are of minor importance. The subfamily Trombiculinae includes the

"harvest" and "chigger mites." They are conspicuous by their brilliant coloration. The widely known chigger, Entrombicula

alfreddugesii (Oudemanus),

is a pest of humans in North America.

Typically in Trombidoidea, the larvae of this species are very tiny

(e.g., E. batatas) and

adhere to blades of grass in wild areas, from which they can transfer in

large numbers to persons walking by.

Then they become larger as they feed on body fluids, and eventually

they drop to the ground to reproduce.

The itching and subsequent scratching around the feeding sites can

result in severe infections. OTHER IMPORTANT SPECIES Eutrombicula batatas (L.) is the "patatta

mite" of South and Central America and the Caribbean. The life cycle

differs slightly in the tropical environment. Trombicula autumnalis

(Shaw) attacks animals and humans in Europe, where severe skin inflammation

can result. In the Far East Trombicula

akamushi (Brumpt) is the cause of "Japanese River Fever." Trombicula

deiiensis Walch of the East Indies attacks animals and

humans. Trombicula fletcheri W. & H. attacks humans in New

Guinea. Many other unidentified

species of Trombicula and other

genera attack humans in the South Pacific. LIFE CYCLE (See Diagram) Trombiculid mites have a complex life cycle and different

terms have been applied to the developmental stages, but the terminology used

by Service (2008) is applied as follows:

Adults of this group are not parasitic but rather inhabit the soil

where they feed on other arthropods.

During warm weather a female mite may lay up to five eggs daily on

organic material located on the soil surface, in field grasses, etc. "Deutorum" larvae with six legs

emerge but initially do not leave the egg shell (the

"Deutovum"). Activity

begins about a week later when the mites swarm all over the soil and

grasses. They try to attach to

mammals and birds as well as to people with which they come into

contact. They gather around soft and

moist areas of a host. The larvae then penetrate into the skin, injecting saliva

that destroys cells. They feed on

lymphal fluid instead of blood. The continued

release of saliva then results a nasty skin reaction. Some species spend a whole month on a

host, but the vectors of Scrub Typhus remain on a host for only

about a week. When fully fed the

larvae exit the host and drop to the ground where they bury into the soil or

under leaf litter, etc. There they

change into a "Protonymph," which moults within week and gives rise

to a "Deutonymph" with eight legs.

The deutonymphs like the adults feed for a couple of weeks on

arthropods in the soil. Feeding stops

and the nymphs change into a "tritonymph" that moults after about

two weeks giving rise to the adult stage.

The total life cycle generally takes up to two months, but sometimes

8-10 months are required. Because nymphs and adults feed on other arthropods they require

habitats where there are sufficient arthropods present to sustain them. Service (2008) noted that ideal habitats

are often produced when vegetation is cleared for agriculture or wood

products. DISEASE ASSOCIATIONS The mites can cause severe itching, which often leads to

infections in humans. But some

species are vectors of disease. Tstsugamushi Disease caused by a virus

was first found in Japan where it is also known as "Japanese River Fever," but it is

now widespread in Asia and Australasia

The virus, Rickettsia orientalis, is transmitted by the bite

of the red mite, Trombicula akamushi,

and a local rodent serves as a reservoir of the virus. Incubation in humans is 7-14 days and

mortality often follows, especially in older people. CONTROL Severe cases of infestation should always require the

attention of a physician, but as with other groups of pestiferous mites

avoidance of infested areas and the use of available repellants is

advisable. Control of breeding sites

in the environment may also be applied to reduce mite infestations. These sites exist as islands in the

vegetation where mites can be reduced by burning or insecticide application. = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

= =

Key References: <medvet.ref.htm> [Additional references may be found at: MELVYL Library] Azad, A. F. 1986. Mites

of public health importance and their control. WHO/VBC/86.931. Geneva, Switzerland Conradt, S. A., T.

J. Corbet, E. J. Roper& J. Bodsworth 2002. Parasitism by the

mite Trombidium breei on four

U.K. butterfly species. Ecological Entomology 27(6): 651-659. Matheson, R. 1950. Medical Entomology. Comstock Publ. Co, Inc. 610 p. Makol, Joanna 2007.

Generic level review and phylogeny of Trombidiidae and Podothrombiidae

(Acari: Actinotrichida: Trombidioidea) of the world. Annales Zoologici 57(1):

1-194 Oudhia, P. 1999.

Traditional medicinal knowledge about red velvet mite Trombidium sp. (Acari: trombidiidae in

Chhattisgarh. Insect Environment 5(3): 113 Service, M. 2008.

Medical Entomology For Students.

Cambridge Univ. Press. 289 p Zhang,

Zhi-Qiang. 1998. Biology

and ecology of trombidiid mites (Acari: Trombidioidea). Experimental & Applied Acarology 22:

139-155. |