|

Arthropoda: Insecta

KEY TO SIPHONAPTERA

OF

MEDICAL IMPORTANCE

(Fleas)

(Contact)

Please CLICK on picture and

underlined links to view or to navigate within the key:

To Search for Subject Matter use Ctrl/F

[Also See: Siphonaptera Details]

There are about 221 genera and over 2,205 species of fleas in

the world. The order has five

families with species of medical importance:

Hectopsyllidae, Dolichopsyllidae, Pulicidae, Hystrichopsyllidae and

Ischnopsyllidae. Thirteen medically

important species are: Ctenocephalides

canis (Curtis) [dog flea], Ctenocephalides felis

(Bouche) [cat flea], Cediopsylla simplex

(Baker) [rabbit flea], Ceratophyllus gallinae

(Schrank) [chicken or hen flea], Ctenophthalmus pseudargyrtes

Baker [Small mammal flea], Echidnophaga gallinacea (Westwood) [stick tight flea], Hoplopsyllus anomalus Baker [rodent flea], Leptopsylla segnis [European

mouse flea], Nosopsyllus fasciatus

(Bosc.) [rat flea], Oropsylla montana (Baker)

[ground squirrel flea], Pulex irritans L. [flea of humans], Tunga penetrans L.

[jigger flea] and Xenopsylla cheopis

(Roth.) [Oriental rat flea]. The

common names of fleas (e.g. "dog flea") are misleading as humans

may also be attacked by any of these species especially when in close

proximity of the preferred host. New

discoveries of medically important species are being made in South America;

e.g., Ectinorus insignis (Beaucournu

et al 2013) and Ctenidiosomus sp. (Lopez-Berrizbeitia et al. 2015). There are about 221 genera and over 2,205 species of fleas in

the world. The order has five

families with species of medical importance:

Hectopsyllidae, Dolichopsyllidae, Pulicidae, Hystrichopsyllidae and

Ischnopsyllidae. Thirteen medically

important species are: Ctenocephalides

canis (Curtis) [dog flea], Ctenocephalides felis

(Bouche) [cat flea], Cediopsylla simplex

(Baker) [rabbit flea], Ceratophyllus gallinae

(Schrank) [chicken or hen flea], Ctenophthalmus pseudargyrtes

Baker [Small mammal flea], Echidnophaga gallinacea (Westwood) [stick tight flea], Hoplopsyllus anomalus Baker [rodent flea], Leptopsylla segnis [European

mouse flea], Nosopsyllus fasciatus

(Bosc.) [rat flea], Oropsylla montana (Baker)

[ground squirrel flea], Pulex irritans L. [flea of humans], Tunga penetrans L.

[jigger flea] and Xenopsylla cheopis

(Roth.) [Oriental rat flea]. The

common names of fleas (e.g. "dog flea") are misleading as humans

may also be attacked by any of these species especially when in close

proximity of the preferred host. New

discoveries of medically important species are being made in South America;

e.g., Ectinorus insignis (Beaucournu

et al 2013) and Ctenidiosomus sp. (Lopez-Berrizbeitia et al. 2015).

The following keys separate the most common Genera and Species involved:

[Please CLICK on Figures to view]

|

KEY TO PRINCIPAL IMPORTANT GENERA

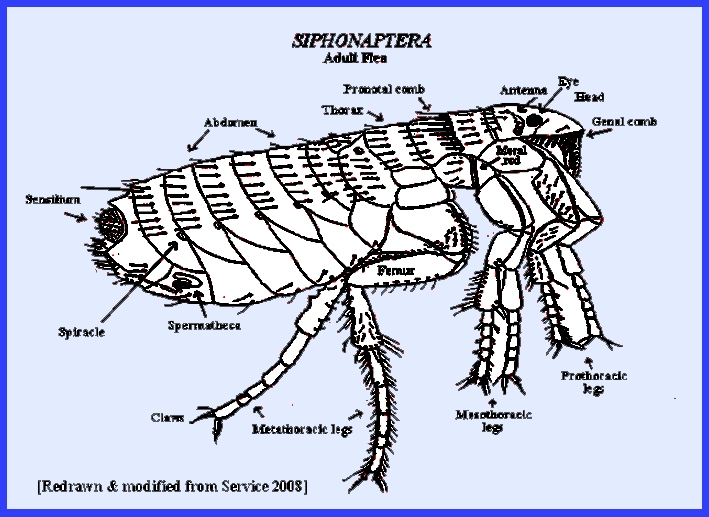

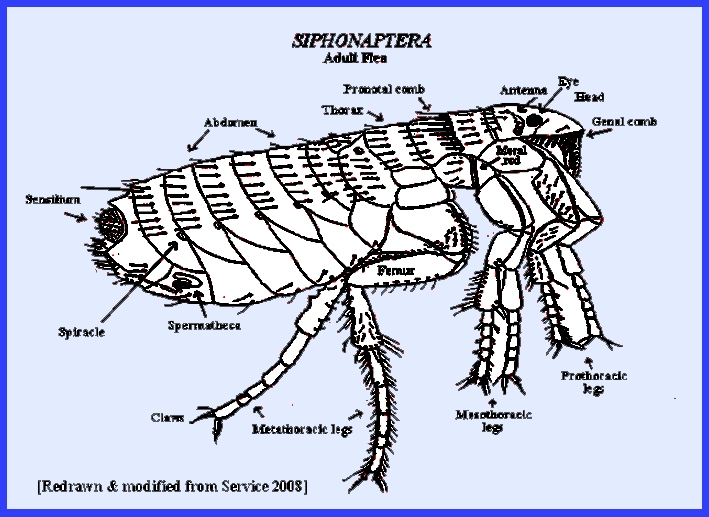

1a. Combs and

Meral Rods on thorax are present (Fig. A, Fig. B, Fig. C) - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 2a

No combs are present on thorax (Fig. D, Fig. E, Fig. F) - -- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4a

2a. Meral rod on

lateral thorax is vertical (Fig. C)- - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Nosopsyllus

spp. (species)

Meral rod is angled (Fig. A, Fig. B) - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 3a

3a. Meral rod on

lateral thorax is strongly angled (Fig. B)- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Leptopsylla spp.

(species)

Meral rod is not as strongly angled (Fig. A) - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Ctenocephalides

spp. (species)

4a. Meral rod is

present on lateral thorax (Fig. F) -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - Xenopsylla spp. (species)

No meral rod is present on lateral

thorax (Fig. D,

Fig. E) - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5a

5a. Antenna on head

extends beyond an eye and first three thoracic segments about equal in size

(Fig. D) - - - - - - - Pulex spp. (species)

Antenna is shorter, not extending

beyond eye and first three thoracic segments are unequal in size (Fig. E) - - - Tunga

spp. (species)

KEY TO PRINCIPAL IMPORTANT SPECIES

1. A greatly reduced

thorax, with terga combined being shorter than the 1st abdominal

tergum. Gravid females are greatly

distended

(Fig. 1) _ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Hectopsyllidae

The

thorax is not reduced and the combined terga are usually longer than the

first abdominal tergum (Fig.

2) _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 3

2. Third leg coxa with a

patch of small spines on the inner surface. Abdominal segments 2 & 3 have spiracles (Fig. 3) _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Echidnophaga gallinacea

Coxa of

3rd leg lacks the small spines.

Segments 2 & 3 of female abdomen lack spiracles. Species confined to warmer climates _ _ _

_ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Tunga penetrans

3. Terga of abdomen

usually with only one cross row of setae (Fig. 4). A groove between the frons and occiput

is usually absent. Eyes are

usually present _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Pulicidae 4

Abdominal terga usually with more than one cross row of setae; There

is usually a groove between the frons and occiput. _ _ _ _ _ 9

4. A genal comb, or

crenidium is absent (Fig.

5c) _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _5

Genal and

pronotal combs are present (Fig. 5a) _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _7

5. Pronotal comb or

ctenidium is absent (Fig.

5c) _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 6

Pronotal comb is present. Flea usually found on ground squirrels (Fig. 5g) _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Hoplopsyllus anomalus

6. Thorax second segment

pleuron divided by a stout, vertical rod like thickening _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Xenopsylla cheopis

Pleuron

is not divided _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Pulex irritans

7. Genal comb teeth are

straight, blunt and with black spines arranged almost vertically (Fig. 5i). usually found on rabbits in North

America

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Cediopsylla simplex

Genal

comb teeth hve 7-8 sharp teeth, and are arranged almost parallel to the

flea's long axis (Fig.

5a) _ Ctenocephalides spp. 8

8. Frons is high & rounded. First 2 spines of genal comb shorter

than the remaining (Fig.

5b) _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Ctenocephaldes canis

Frons

is low, flat and almost pointed.

Spines of the genal comb are about of equal length (Fig. 5a) _ _ _ _ _

_ Ctenocephalides felis

9. The head is a bit

elongated and 2-3 ventral flaps are present on each side near the fronto

genal angle (Fig. 5i). These fleas are

parasites of bats. _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Ischnopsyllidae

Head is

not elongated and there are no ventral flaps. Fleas are not bat parasites

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 10

10. Genal comb absent, but combs on abdominal terga often present. Hexactenus ischnopsyllus _ _ _ Dolichopsyllidae 11

The

genal comb is present, but the combs on the abdominal terga are often

present _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Hystrichopsyllidae 12

11. The pronotal comb has

12 or more spines on each side _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _Ceratophyllus gallinae

Pronotal comp has less than 12 spines on each side (Fig. 5d). On male the finger of clasper is short,

broad, flattened and has spines

but

no black spinifrons _ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _Nosopsyllus fasciatus

Movable finger of the clasper elongated &

sword-shaped. On ground squirrels

that carry plague (Fig.

5e) _Oropsylla montana

12. Genal comb contains 3 sharp

teeth directed backward. Usually

found on small rodents _ _ _ _Ctenophthalmus pseudargyrtes

Genal

comb has 4 blunt teeth directed backwards. (Fig. 5h). Common on rodents _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Leptopsylla segnis

|

- - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - -

Key References: <medvet.ref.htm> <Hexapoda>

Azad, A. F. 1990.

Epidemiology of murine typhus.

Ann. Rev. Ent. 35: 553-69.

Azad, A. F. & C. B.

Beard. 1998. Rickettsial pathogens and their arthropod

vectors. Emerging Infectious Diseases

4: 179-86.

Beaucournu, J-C. 2013. A new flea, Ectinorus

insignis n. sp. (Siphonaptera, Rhopalopsyllidae, Parapsyllinae),

with notes on the subgenus Ectinorus

in Chile and comments on unciform sclerotization

in the superfamily Malacopsylloidea. Parasite 20(35).

Bishopp, F. C. 1931.

Fleas and their control. U.S.

Dept. Agr., Farmers' Bull. 897.

Eisle, M. , J. Heukelbach &

van Marck, E. et al. 2003. Investigations on the biology, edpidemiology, pathology and

control of tunga penetrans in

Brazil:

I. Natural history in man. Parasitology Res. 49: 557-65.

Ewing, H. E. 1924.

Notes on the taxonomy and natural relationships of fleas, with

descriptions of four new species.

Parasitology 16: 341-254.

Ewing, H. E. & I.

Fox. 1943. The fleas of North America.

U.S. Dept. Agr. Misc. Pub. 500.

Fox, Irving. 1940.

Fleas of the eastern United States.

Ames, Iowa Press

Gage, K. L. & Y.

Kosoy. 2005. Natural history of plague: perspectives

from more than a century of research.

Ann. Rev. Ent. 50: 505-28.

Gratz, N. G. 1999.

Control of plague transmission.

IN: Plague Manual: Epidemiology, Distribution, Surveillance &

Control. WHO, Geneva. pp. 97-

134

Hechemy, K. E. & A. F. Azad. 2001. Endemic

typhus, and epidemic typhus. IN: The Encyclopedia of Arthropod-Transmitted

Infections of Man and

Domesticated Animals. CABI, pp. 165-69 & 170-74.

Heukelbach, J., A. M. L. Costa, T.

Wilcke & N. Mencke. 2004. The animal reservoir of Tunga penetrans in severely affected communities

of north-east

Brazil. Med. & Vet. Ent. 18: 329-35.

Heukelbach, J., A. Franck & H.

Feldmeier. 2004. High attack rate of Tunga penetrans (L. 1758) infestations in an

impoverished Brazillian community.

Trans. Roy Soc. Trop. Med. & Hyg. 98: 43-44.

Hinkle, N. C., P. G. Koehler, W. H.

Kern & R. S. Patterson. 1991. Hematophagous strategies of the cat flea

(Siphonaptera: Pulicidae).

Florida Ent. 73: 377-85.

Hinkle, N. C., P. G. Koehler & R.

S. Patterson.1995. Residual effectiveness

of insect growth regulators applied to carpet for control of cat flea

(Siphonaptera: Pulicidae) larvae. J. Econ. Ent. 88: 903-6.

Hinkle, N. C., M. K. Rust & D. A. Reierson. 1997.

Biorational approach to flea (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae) suppression:

present and future. J. Agric.

Ent.

14: 309-21.

Hinkle, Nancy C., Philip G. Koehler,

and Richard S. Patterson. 1990. Egg

production, larval development and adult longevity of cat fleas

(Siphonaptera: Pulicidae) exposed to ultrasound. J. Econ. Entomol. 83(6): 2306-2309.

Hubbard, C. A. 1947.

Fleas of western North America.

Ames, Iowa Press.

Lopez-Berrizbeitia, M. F. et al.

2015. A new flea of the genus Ctenidiosomus (Siphonaptera, Pygiopsyllidae)

from Salta Province, Argentina.

Zoo Keys 512: 109-120.

Matheson, R. 1950. Medical Entomology. Comstock Publ. Co, Inc. 610 p.

Pugh, R. E.

1987. Effects on the

development of Dipylidium

caninum and on the host reaction to this parasite in the

adult flea

(Ctenocephalides felis). Parasitol. Res.

73: 171-77.

Rothschild, N. C. 1910.

A synopsis of the fleas found on Mus norvegicus, Mus rattus and Mus musculus.

Bull. Ent. Res. 1: 89-98.

Rust, M. K. 2005.

Advances in the control of Ctenocephalides

felis (cat flea) on cats and dogs. Trends in Parasitol. 1: 232-36.

Rust, M. K. & M. W.

Dryden. 1977. The biology, ecology and management of the

cat flea. Ann. Rev. Ent. 42: 451-73.

Schriefer, M. E., J. B. Sacci, J. P. Taylor, J. A.

Higgins & A. F. Azad. 1994. Murine typhus: updated roles of multiple

urgan components and a second

typhuslike rickettsia. J. Med. Ent. 31: 681-85.

Service, M. 2008.

Medical Entomology For Students.

Cambridge Univ. Press. 289 p

Scott, S. & C. J.

Duncan. 2001. Biology of Plagues: Evidence from Historical Populations. Cmbridge Univ. Press, England.

Traub, R. & H. Starcke (eds.) 1980. Fleas. Proc. Intern. Conf. on Fleas, Ashton Wold,

Peterborough, UK, 21-25 Jun 1977.

Rotterdam: Balkema.

|