File: <sarcoptoidea.htm> <Medical

Index> <General Index> Site Description <Navigate to Home>

|

Acarina SARCOPTOIDEA (Parasites of

Birds, Mammals & Insects) (Contact) Please CLICK on

Image & underlined links to view:

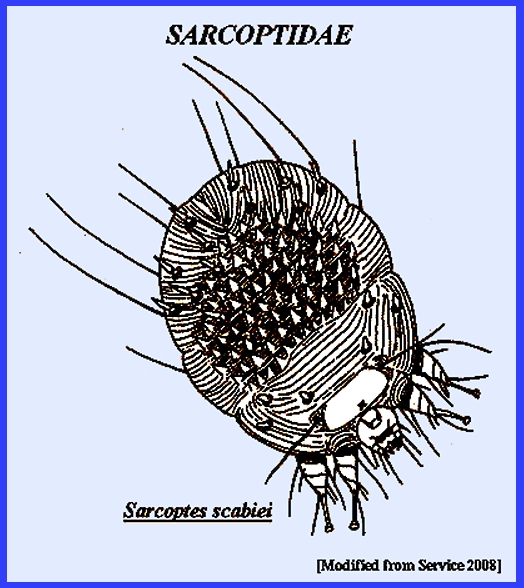

GENERAL APPEARANCE (See Photo). Females are

very tiny at barely 1/2 mm They are of pale color and rounded. There are many small spines on the dorsum

and several lines across the top and bottom of the body. The four pairs of legs are short and

cylindrical consisting of five ringed segments (Service 2008). The anterior two pairs of legs terminate

in short pedicels with suckers at the tips.

The posterior two leg pairs in females do not have suckers, ending

instead with bristles. The head is

not clearly defined, but thick short palps and chelicerae of mouthparts

extend forward from the body. LIFE CYCLE The mite

females excavate below the skin's surface where it is thin as around wrists,

fingers, feet, etc. However, most are

found on the hands and wrists and sometimes they also infest the head region

of their hosts. Once under the skin

females create winding tunnels and feed on liquids produced by the dermal

cells. About 1-3 eggs are laid daily

in the tunnels, which then require about four days to hatch with small larvae

that have only six legs. The larvae

migrate to the skin's surface where most perish, but the survivors seek out a

hair follicle where they moult and develop into a "protonymph) with

eight legs. A "tritonymph"

is produced after about 3-4 days.

Service (2008) noted that female nymphs are much larger than male

nymphs. About 3 days later the

tritonymph moults to produce either a male or female adult. Mated females then increase their size and

begin their penetration into skin.

Males, on the other hand, are much smaller and wander about the skin

surface and construct short dens for refuge.

The total life cycle usually requires less than two weeks, and females

may live up to six weeks on their hosts, but perish in a few days without

hosts. MEDICAL IMPORTANCE Skin

diseases, known as Scabies, Acariasis,

Sarcoptic Itch, etc., are

produced in humans and animals. Some

of the Sarcoptes spp.

actually inhabit tunnels underneath the skin. These mites may pass their entire lives on their hosts. Infestations among hosts are acquired by

contact. It has been estimated that

over 300 million cases of Scabies

occur annually worldwide. One family,

Sarcoptidae, and genus, Sarcoptes, is of

principal importance for humans. Sarcoptes scabiei is known as the "Human Itch Mite," of "Norwegian Itch" as it is sometimes

called. Females that are larger than

males have the dorsal part of the body marked with distinctive parallel

lines. The mites locate in the upper

layers of epidermis especially around the groin and more sequestered

areas. Mature females that bore

directly into skin where they remain concealed for a while construct egg

tunnels. Enlarging the excavation and

laying eggs follow this. Eggs hatch

in 3-4 days and the larvae leave the tunnel for the skin surface where they

enter hair follicles. Molting occurs

in 2-3 days followed by two nymphal stages.

Nymphs construct narrow tunnels where mating occurs. The life cycle varies from 8-15 days at

room temperature. Adult longevity is

3-5 weeks. A person may

acquire 50 or more mites at any given time, and any infections that develop

are not obvious for several weeks.

Following an attack there are at first few symptoms. Gradually as one becomes sensitized an

intense itching ensues, which is especially intense at night. Infections are more likely the more one

scratches the infested areas. Acquisition

of mites is through close contact with infested persons or their

clothing. Avoidance of infested areas

is preferred, but if infected one should seek medical attention from a

physician, for current products available for treatment. There are also

species (eg., Psoroptes communis and Notoedres cati itch mites

attacking animals that do not tunnel bur rather possess suckers for exterior

attachment to the skin. Humans only

become affected from close contact with infested animals, such as cats and

rats. CONTROL The attention

of a medical physician is advised for this group of mites, as medicinal

treatment is usually required.

Prevention involves the usual precautions of cleanliness and limiting

contact with infected surfaces, animals and people. However, Service (2008) recommended that during epidemics

clothing and bedding should be dry cleaned or washed in 50-deg. Centigrade

water. (Also See: Scabies) = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = Key References:

<medvet.ref.htm> [Additional references may be found at:

MELVYL Library] Arlian, L. G. &

M. S. Morgan. 2000. Serum antibody to Sarcoptes scabiei and house dust mite prior to and during infestation with S. scabiei. Vet. Parasitol. 90:315326. Arlian, L. G.,

Morgan MS, Neal J.S. 2003. Modulation

of cytokine expression in human keratinocytes and fibroblasts by extracts of

scabies mites. Am J Trop. Med Hyg. 69: 652656 Arlian, L. G., M. S.

Morgan, & J. S. Neal. 2004. Extracts of scabies mites (Sarcoptidae: Sarcoptes scabiei) modulate cytokine expression by human peripheral blood mononuclear

cells and dendritic cells. J Med Entomol. 41: 6973. Arlian, L. G., M. S.

Morgan, C. M. Rapp & D. L. Vyszenski-Moher. 1996. The development of protective immunity in

canine scabies. Vet. Parasitol. 62: 133142. Arlian, L. G., C. M. Rapp, B. L. Stemmer, M. S. Morgan

& P. F. Moore. 1977.

Characterization of lymphocyte subtypes in scabietic skin lesions of naοve and sensitized dogs. Vet. Parastitol. 68: 347358. Arlian, L. G., C. M.

Rapp, D. L. Vyszenski-Moher & M. S. Morgan. 1994. Sarcoptes scabiei: Histopathological changes associated with acquisition and expression of host

immunity to scabies. Exp. Parasitol. 78: 5163. Kemp, D. J, S.

F. Walton, P. Harumal, & B. J. Currie .

2002. The scourge of scabies. Biologist. 49: 1924. Matheson, R. 1950. Medical Entomology. Comstock Publ. Co, Inc. 610 p. Service, M. 2008.

Medical Entomology For Students.

Cambridge Univ. Press. 289 p Maxwell,

S. S., T. A. Stoklasek, Y. Dash, J, R., Macaluso & S. K. Wikel. 2005.

Tick modulation of the in-vitro expression of adhesion molecules by skin-derived endothelial cells. Annals Trop Med Parasitol. 99: 661672. Orkin,

M, H. Maibach, L. C. Parish & L. M. Schwartzman. 1977. Scabies and pediculosis. Lippincott

Co., Philadelphia. p. 203. Stemmer BL, Arlian

L. G., M. S. Morgan, C. M. Rapp &

P. F. Moore. 1996. Characterization of antigen presenting

cells and T-cells in progressive scabiatic skin lesions. Vet Parasitol. 67: 247258. |