File: <rockymountainfever.htm> <Medical

Index> <General Index> Site Description Glossary <Navigate

to Home>

|

ROCKY MOUNTAIN SPOTTED FEVER (Alternate Names = Mexican Spotted Fever & São Paulo Spotted Fever) (Contact) Please

CLICK on

Image & underlined links for details: Two strains of the disease, a mild and a virulent type,

exist through most regions where the disease is a problem. Mortality varies from around 80 percent

for the virulent strain and about 4-6 percent for the mild strain. The disease was named, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever"

because of its apparent origin. The

causative agent is Rickettsia rickettsii. It is not contagious, but highly infectious

and transmitted to humans by ticks.

Service (2008) noted that is both transovarial and transstadial. Early

investigations revealed that the disease is mainly an infection of small

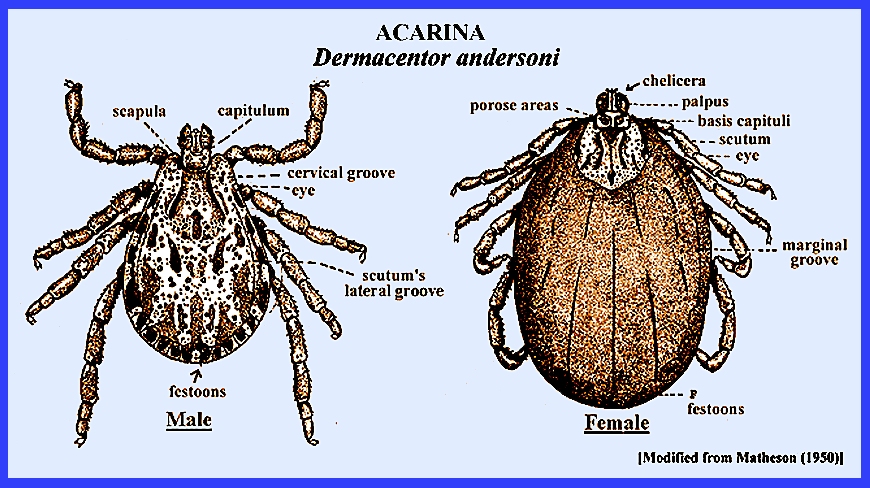

mammals, and large mammals, excluding humans, are not susceptible. Principal tick species involved include Dermacentor andersoni, and to

a restricted area Dermacentor sanguineus,

which are the vectors for humans in western North and Central America. Dermacentor variabilis

is the vector tick in eastern North America, while in South America Amblyomma

cajennense is the principal vector. Other vector species undoubtedly exist, such as Dermacentor

occidentalis and the rabbit tick, Haemaphysalis

leporis-palustris, which does not attack humans but can

maintain the Rickettsia in the

rodent population. Laboratory

transmission trials have succeeded with additional vector species as well. Studies have shown that the incubation period in humans

after the bite of infectious ticks varies from 2 to 12 days. Service (2008) reports that as an

infective tick has to feed on a host for at least two hours before sufficient

Rickettsiae are injected for

the host to become infected, early tick removal may prevent

transmission. Although Matheson

(1950) reported on a vaccine that gave some protection for almost one year,

there was no mention of it by Service (2008). LIFE CYCLE -

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

= = Key References: <medvet.ref.htm> <Hexapoda> Camicas, J. L., J. . Hervy, F. Adam & P. C.

Morel. 1998. The ticks of the world (Acarida,

Ixodida): Nomenclature, Described

Stages, Hosts, Distribution. Paris: Editions de l'ORSTOM. Dumler, J. S. & D. H. Walker. 2005.

Rocky mountain spotted fever: changing ecology and persisting

virulence. New England J. of Medicine 353:

551-53. Gammons, M. & G.

Salam. 2002. Tick removal. Amer. Fam. Physician 66:

643-45. Gothe, R., K. Kunze

& H. Hoogstraal. 1979. The mechanisms of pathogenicity in the

tick paralyses. J. Med. Ent. 16: 357-69. Hoogstraal, H. 1966.

Ticks in relation to human diseases caused by viruses. Ann. Rev. Ent. 11: 261-308. Hoogstraal, H. 1967.

Ticks in relation to human diseases caused by Rickettsia species. Ann. Rev. Ent. 12: 377-420. Jellison, W. L.

1945. The geographical distribution

of Rocky Mountain spotted fever and Nuttall's cottontail in the western

United States. U. S. Pub. Hlth. Repts. 60: 958-961. Matheson, R. 1950. Medical Entomology. Comstock Publ. Co, Inc. 610 p. Service, M. 2008.

Medical Entomology For Students.

Cambridge Univ. Press. 289 p. Needham, G. R. & P.

D. Teel. 1991. Off-host physiological ecology of ixodid

ticks. Ann. Rev. Ent. 36: 313-52. Parola, P. & D. Raoult. 2001.

Tick-borne typhuses. IN: The Encyclopedia of arthropod-transmitted

Infections of Man and Domesticated Animals. ed. M. W. Service,

Wallingford: CABI: pp. 516-24. Sonenshine, D. E., R. S. Lane & W.

L. Nicholson. 2002. Ticks

(Ixodida). IN: Medical & Veterinary Entomology, ed. G. Mullen & L.

Durden, Ambsterdam Acad. Press. pp 517-58. Sonenshine, D. E. &

T. N. Mather (eds.) 1994. Ecological Dynamics of Tick-Borne

Zoonoses. Oxford Univ. Press, New

York. Steer, A., J. Coburn & L. Glickstein. 2005.

Lyme borreliosis. IN: Tick-Borne Diseases of Humans, ed. J. L.

Goodman, D. T. Dennis & D. E. Sonenshine, Washington, DC: ASM

Press. Wolbach, S. B. 1919. Studies on Rocky Mountain spotted fever. J. Med. Res. 41: 1-197. |