File: <leishmaniasis.htm> <Medical Index> <General Index> Site Description Glossary <Navigate

to Home>

|

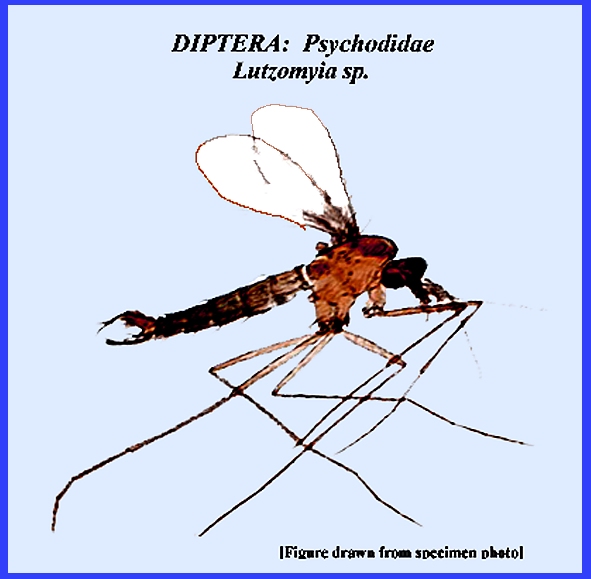

LEISHMANIASIS & Sandflies (Contact) Please

CLICK on

underlined links for details: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Diffuse

Cutaneous Leishmaiasiss Mucocutaneous Leishmaniasis Visceral

Leishmaniasis The life

cycle begins when amastigote

parasites are ingested by female sand flies during a blood meal. the parasites multiply in the sandfly

intestines and turn into promastigotes,

which are elongated and have a flagellum that attaches to the mid- or

hind-intestinal wall where they multiply.

Those that are not voided migrate to the anterior mid-intestines and

then to the fore-intestines. There

some parasites change into metacyclic

forms. After 4-12 days after

the sandfly has has an infected blood meal the metacyclic forms are found in

the mouthparts from which they may be introduced to a new host during feeding. Transmission is maximized because infected

sandflies probe more frequently.

Because sandflies also feed on plants containing sugar, this aids

parasite development. (Also see Life

Cycle) Most

leishmaniasis are zoonoses,

and the degree of human involvement varies in different areas (Service

2008). The epidemiology is mostly

determined by the sandfly species, their ecology and behavior as well as the

strains of Leishmania

parasites. Sometimes the sandflies

transmit infections mostly among wild or domestic animals with little human

involvement. In other areas the

animals may serve as reservoir hosts for human infection. The disease may also be transmitted

between people by sandflies with animals taking no part in its transmission

(e.g., India). Following are more

details concerning the different forms of the disease as given by Service

(2008): Sometimes

known as "Oriental

Sore" this form of leishmaniasis occurs principally in arid

parts of the Middle East to India, Asia and Africa. The principal parasites are Leishmania

major, which are vectored by Phlebotomus

papatasi, and Leishmania

tropica is vectored by Phlebotomus sergenti. Leishmania

major is mainly zoonotic and gerbils are the reservoir hosts. Leishmania

tropica is in densely populated areas where humans are the

principal reservoir hosts. In America

the cutaneous form occurs mainly in forested parts of Mexico south to

northern Argentina. It is caused by Leishmania braziliensis (= amazoniensis) and Leishmania mexicana. Dogs and rodents are probably the

principal reservoir hosts. The main

vectors are Lutzomyia wellcomei

and Lutzomyia flaviscutellata. This is a very

severe form of the disease that occurs from Mexico to Argentina and is caused

by Leishmania braziliensis. Dogs are reservoir hosts and Lutzomyia wellcomei a principal vector. Diffuse Cutaneous Leishmaiasiss Cutaneous nodules all over the body

characterize this form. It occurs in

Venezuela, the Dominical Republic and the highlands of Ethiopia and Kenya. In South America the parasite is Leishmania amazonensis, which is

vectored by Lutzomyia flaviscutellata. Spiny rats are reservoir hosts. In Africa the parasite is Leishmania aethiopica vectored by Phlebotomus pedifer and P. longipes. Rock hyraxes are reservoir hosts. Also known as "kala-azar"

this form is caused by Leishmania donovani

donovani. It occurs in

India, Sudan, Ethiopia and East Africa.

Vector species include Phlebotomus

argentipes and Phlebotomus

orientalis. Wild cats,

genets and rodents may be the main reservoir hosts. In the Mediterranean area and central Asia Leishmania donovani infantum is the

parasite , which is vectored by Phlebotomus

ariasi and Phlebotomus perniciosus. Foxes and dogs are reservoir hosts. This form also occurs at times in Central

and South America where the parasite is Leishmania

donovani infantum and is vectored by species of the Lutzomyia longipalpis

complex (Service 2008). Control or avoidance of the sandfly

vectors is required to reduce incidence of infection (Alexander & Maroli

2003). Insecticidal control of vector

sandflies is effective until resistance sets into the fly population. Therefore, the use of repellants is

preferable. To reduce diseases caused

by sandflies some efforts have been made to eliminate reservoir hosts from

populated areas. Further efforts to

control the vectors remain experimental, especially as the breeding sites of

most sandflies are not easily found. Lieshmania

& Phlebotomus - Life Cycles = = = = = = = = = = = =

= = = = = = = = Key References: <medvet.ref.htm> <Hexapoda> Alexander, B. & M. Maroli. 2003.

Control of phlebotomine sandflies.

Med. & Veterinary Entomology 17:

1-18. Ashford, R. W.

2001. Leishmaniasis. 2001. IN: Encycl. of

Arthropod Transmitted Infections of Man & Domesticated Animals. CABI pp. 269-79. Guerin, P.

J., P. Olliaro & S. Sundar et

al. 2002. Visceral leishmaniasis: current status of

control, diagnosis & treatment, & a proposed research & development agenda. Lancet Infect. Diseases 2: 494-501. Hide, G, J. C. Mottram, G. H.

Coombs & P. H. Holmes. 1996. Trypanosomiasis and Leishmaniasis. Biol. & Control, Wallingford: CAB internat. Killick-Kentrick, R.

1999. The biology

of phelebotomine sand flies. Clinics

in Dermatology 17: 279-89. Lainson, R. 1983. The American leishmaniases: some

observations on their ecology and epidemiology. trans. Roy Soc. Trop. Med.

Hyg. 77: 569-96. Lane, R. P.

1991. The contribution of

sand-fly control to leishmaniasis control.

Ann. Soc. Belge de Medicine Trop. 71:

65-74. Legner, E. F. 1995.

Biological control of Diptera of medical and veterinary importance. J. Vector Ecology 20(1): 59_120. Legner, E. F. 2000.

Biological control of aquatic Diptera. p. 847-870.

Contributions to a Manual of Palaearctic Diptera, Vol. 1, Science

Herald, Budapest. 978 p. Matheson, R. 1950.

Medical Entomology. Comstock

Publ. Co, Inc. 610 p. Service, M.

2008. Medical Entomology For

Students. Cambridge Univ. Press. 289 p Tayeh, A., L.

jalouk & A. M. Al-Khiami. 1997.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis control trial using pyrethroid-impregnated

bednets in villages near Aleppo, Syria. WHO/LEISH 97.41. Geneva: WHO Div. of Control of Tropical Diseases. Ward, R. D.

1990. Some aspects of the

biology of phlebotomine sand-fly vectors.

Adv. Dis. Vector Res. 6:

91-126. |