File: <cimicidaemed.htm> <Medical

Index> <General Index> Site Description Glossary <Navigate

to Home>

|

Arthropoda

- Insecta HEMIPTERA: Cimicidae (Bedbugs) (Contact) Please CLICK on

Image & underlined links for details:

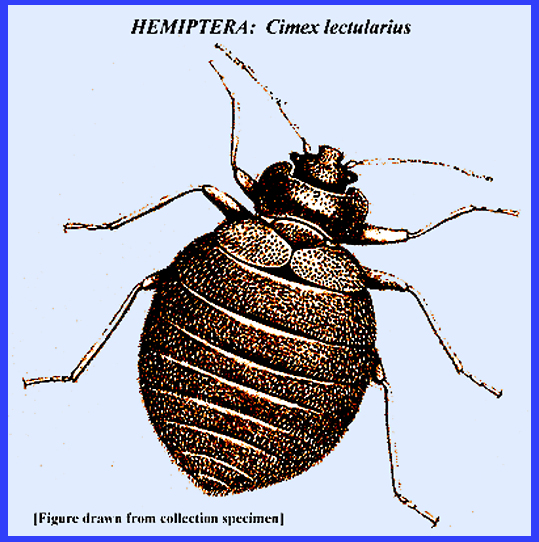

APPEARANCE Bedbug adults

are wingless and flattened dorsoventrally.

Their size averages about 5-7 mm long. The head is short and broad and has a pair of prominent

compound eyes in front of which is a pair of 4-segmented antennae. The proboscis is thin and usually held close

to the body underneath the head and prothorax. The prothorax is larger than the meso and metathorax, and

possesses winged expansions.

Hemelytra are present, which have no function. Legs are well developed and slender. Eight

abdominal segments are visible even though there are eleven. The male abdomen is more pointed than the

female. Service (2008) noted that

females have a small incision ventrally on the fourth abdominal segment,

which opens into a pouch called the mesospermalege or the Berlese Organ. It is used to store sperm after

mating. Both sexes draw blood from

their hosts. LIFE CYCLE Bedbugs draw

blood from their hosts primarily at night, but if stressed will do so also

during daytime. The bugs usually

retreat to hiding places when they are finished feeding, and thus do not

often remain in contact with people.

Their hosts include rodents, bats and birds when humans are

unavailable. Both adults and nymphs

are inactive during daytime hiding in dry cracks, furniture ceilings,

wallpaper, mattresses, etc. They

resume activity at night but will return to hiding places after blood meals. Bizarre

indeed is the mating procedure among the Cimicidae, which was explained by

Service (2008). Males penetrate the

integument to incorporate spermatozoa in a "Berlese Organ" that is

located on the female's ventral part of the abdomen. Subsequently the spermatozoa pass into the

haemocoel (body cavity) from which they gain access to the oviducts and eggs. The female

lays three or less eggs per day in building crevices and furniture if the

temperature is above 13 deg. Centigrade.

The 1-mm. long eggs are white or tan, slightly curved and covered with

a mosaic pattern. Female longevity

varies from a few weeks to months and even years. They can lay up to 500 eggs in a lifetime. Hatching depends on temperature but vries

from eight to eleven days. Eggs that

have not hatched may survive for three months. Hatching produces the nymphs, which like lice resemble the

adults. In this hemimetabolous cycle

there are five nymphal stages, each being able to draw blood. The duration of the nymphal stages varies

from two to seven weeks but again may be longer at lower temperatures. Living

bedbugs are easily detected as well as by the casts left by the nymphs during

moults. Wherever they roam they leave

tiny dark colored marks, such as on the beds and walls. There is also an undesirable odor in

dwellings where there are high infestations.

They tend to remain in single dwellings without much dispersal. Spread is frequently with infested

furniture. MEDICAL IMPORTANCE Hepatitis and

other pathogens have been recorded in bedbugs (Mayans et al. 1994), but

vectoring infections to humans is not substantiated (Service 2008). However, their presence causes distress

even though there are few reactions from their feeding activity. Because they draw blood high infestations

can result in iron deficiency in some young and older people especially. CONTROL Repellents

and the use of pyrethrum coils afford protection, but insecticidal sprays are

required for structures and furniture in case of heavier infestations. Service (2008) also noted that insect

growth regulators have sometimes been used for control. = = = = = = = = = = = =

= = = = = = = = Key References: <medvet.ref.htm> <Hexapoda> Johnson, C. G. 1941.

The ecology of the bedbug, Cimex lectuiarius L., in Britain. J. of Hygiene, Cambridge 41: 345-461. Legner, E.

F.

1995. Biological

control of Diptera of medical and veterinary importance. J. Vector Ecology 20(1): 59_120. Legner, E. F.. 2000.

Biological control of aquatic Diptera. p. 847_870. Contributions

to a Manual of Palaearctic Diptera, Vol. 1, Sci. Herald, Budapest. 978 p. Matheson, R. 1950. Medical Entomology. Comstock Publ. Co, Inc. 610 p. Mayans, M. V., A. J.

Hall, H. M. Inskip, et al. 1994. Do bedbugs transmit hepatitis B? Lancet 3453: 761-763. Olesen, Jacob. 2017.

Bed Bug Bites-Pictures, Treatment & Prevention. http://www.bedbugsbites.net/. Reinhardt, K. &

M. T. Siva-Jothy. 2007. Biology of bed bugs (Cimicidae). Ann. Rev. Entomol. 52: 351-374. Ryckman, R. E., D. G. Bentley & E. F.

Archbold. 1981. The Cimicidae of the Americas and Oceanic

Islands: a checklist and bibliography. Bull. Soc. Vector Ecologists: 6-93-142. Service, M. 2008.

Medical Entomology For Students.

Cambridge Univ. Press. 289 p Usinger, R. L. 1966.

Monograph of Cimicidae (Hemiptera-Heteroptera). Thomas Say Found, Vol. 7, Maryland: Ent. Soc. Amer. Venkatachalam, P. S. & B.

Belavady. 1962. Loss of haemoglobin iron due to excessive

biting by bed bugs: a possible

aetiological factor in the iron deficiency anaemia of infants and children. Trans. Roy. Soc. Tropical Med. & Hygiene 56: 218-21. Weidhaas, D. E.

& J. Keiding. 1982. Bed bugs.

Mimeo. document WHO/VBC/82.857.

World Health Organization, Geneva. |