File: <arachnidamed.htm> <Medical Index> <General Index> Site Description Glossary <Navigate

to Home>

|

Arthropoda:

ARACHNIDA Ticks, Mites

Spiders Pseudoscorpions (Contact) Please CLICK on Images to enlarge & underlined links for details: GENERAL

CHARACTERISTICS OF ARACHNIDA

The general

characteristics are the absence of antennae and a body comprised of a cephalothorax and an abdomen, the

latter may appear as only a single part without divisions. The cephalothorax

bears four pair of walking legs and 6-8 eyes raised on tubercules. The head

appendages include chelicerae,

which are jaw like with claws and poison

duct openings at their tips.

The basal portion of pedipalps

serves both feeding and sensory functions. The Arachnida

are air-breathing arthropods, the body of which is divided into two

parts: (1) The cephalothorax,

including the fused head and thorax, and (2) The abdomen. The abdomen can be

either segmented or unsegmented. The mites and ticks have their entire body

fused to form forms a sac. The head appendages are highly modified. The antennae are lateral and the eyes,

when they occur, are simple and sessile, and the eyes, when present, are

rather simple and sessile. In the adults there are four pairs of ambulatory

legs that are attached to the cephalothorax. The first developmental stage is

the larva, which has three pairs of legs.

When respiratory organs occur they are either book lungs or

tracheae. The sexes differ

structurally and metamorphosis is incomplete. The immatures resemble small adults. The arachnids imbibe fluid from their prey by means of a

"sucking stomach."Their mouthparts function either for crushing

their prey and sucking up the liquid portions or for piercing and cutting the

host tissues to obtain blood (Matheson 1950). The

mouthparts consist of a pair of chelicerae located in front of the mouth

opening; a pair of pedipalpi that are located on the mouth sides or just

posterior to them. In some parasitic

species there is a structure called the "hypostome" that is located

directly beneath the mouth opening.

Chelicerae vary structurally in different orders. In the spiders (Araneida) each chelicera

consists of a large basal segment and a terminal one shaped into a claw. Spiders used these structures to capture

and kill their prey. A poison gland

is located near the tip of the claw.

Parasitic species (e.g., ticks) use the chelicera as piercing and

cutting tools. The pedipalpi resemble legs in all the groups have 4-6

segments. In the spiders the pedipalpi 4 of the male are greatly modified

into very specialized organs insemination of females. Among many of the ticks

they are protect the highly developed piercing organs (Matheson 1950). The following

descriptions include both groups of medical and non-medical importance for

distinction purposes: - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - The Order Araneae -- includes the true

spiders. Segmentation is obscure in

the abdomen and there are no obvious appendages except 3-4 pairs of

spinnerets at the posterior end of the abdomen that are modified abdominal

appendages. Several examples of

spiders may be seen in the following diagrams Inv143 - Inv147: Food & Digestion -- Insects and

other small animals are caught in webs.

The prey is paralyzed and their liquid contents are moved up through

the pharynx and esophagus. A sucking stomach pumps food from the

prey through the mouth and into the digestive tract. Nine

diverticulae from the intestine lead to various body parts. There is one located forward and four on

each side, which function to increase the surface area. The posterior part of the intestine is

surrounded by digestive glands and some food may actually enter the

glands. A rectal caecum occurs at the junction of the rectum and

intestine. Circulation -- The heart is long and

located in the abdomen. The dorsal aorta in the cephalothorax

has subsequent branches to appendages and the brain and eye regions. Some blood is pumped posteriorly to a

short posterior aorta. The haemocoel is divided into various

sinuses. Blood reaches the book lungs

and is aerated after which it returns to the heart. Respiration -- Air diffuses directly

into the book lungs, as the

blood does not carry oxygen. Some

tracheae may occur but they are never well developed. Excretion -- Malpighian tubules

serve for excretion. Coxal glands that are modified

nephridia may also be involved in excretion. Nervous System -- There is a typical

pattern where a great concentration of ganglia occurs in the anterior

cephalothorax. Nerves run out to

different parts of the body. Sensory Organs -- There are the

eyes, pedipalps and setae all over the body all of which have sensory

functions. Reproduction -- The sexes are

separate. Ducts open near the

anterior end of the body, but fertilization is internal. Males use

pedipalps to transfer sperm from their genital pore to that of the

female. Eggs are laid in silken

cocoons and maternal care is common.

Development is direct. Silk

Glands -- There are several varieties of silk glands. The silk they produce differs in strength,

slipperiness, etc. Different kinds of

webbing are produced for particular circumstances. The tips of the legs are modified for walking on the webs. Economic Importance -- Some species

of spiders are poisonous to humans and animals. Spider silk has been used in bombsights during World War II. ------------------------------------ Order: Scorpiones

(Scorpionida) -- scorpions: These

animals have a well marked cephalothorax and segmented abdomen that is

equipped with a sting and poison gland at the posterior end. They can be dangerous in warmer

regions. Chelicerae and pedipalps are

both chelate. They have book

lungs. They feed on other

arthropods. They are also viviparous

as they bear living young. See Inv150 & Inv151 for examples: ------------------------------------ Order:

Amblypygi. (Pedipalpia) -- whip spiders and tailless whip scorpions: There is a long tail, large palps and

small chelicerae. ------------------------------------ Order:

Pseudoscorpionida -- book scorpions:

These are small animals that have the appearance of scorpions because

their pedipalps are pincers. The

abdomen is rounded but without a sting.

They feed on small insects. See Inv152 for example: ------------------------------------ Order:

Opiliones (Phalangida) -- harvestmen: Their

extremely long walking legs have earned them the name of "Daddy Long Legs." The body regions are all compacted into a

single division. They are predators

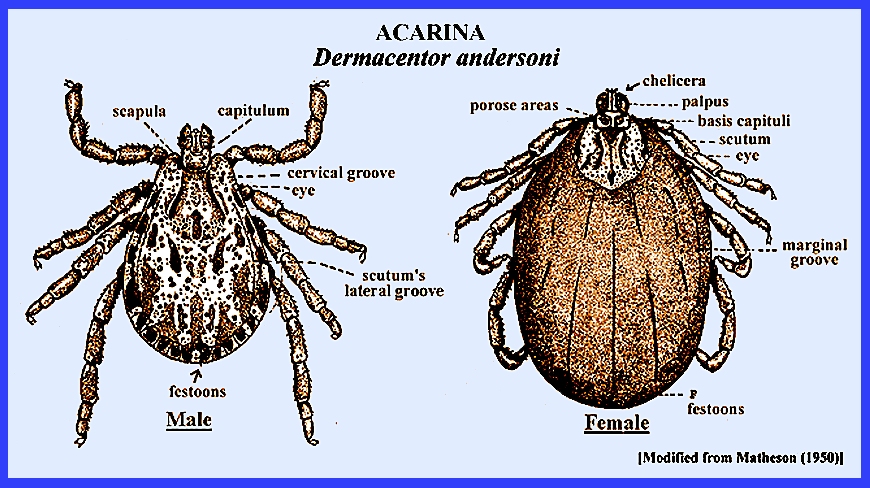

of small insects and other arachnids. See Inv154 for example: ------------------------------------ Order: Acarina -- mites and ticks:

The chelicerae and pedipalps are modified into projections called a hypostome. They are parasites and vectors of disease, and serious pests of

vegetable and tree crops. See Inv153 for example: ------------------------------------ Class Pycnogonida -- sea spiders: These are tiny marine animals. Included are parasites, commensals and

free-living predators. ------------------------------------ Class: Merostomata: Order: Xiphosura -- horseshoe crab:

The range is from the East Coast of North America to the coasts of

southeastern Asia. These animals have

remained essentially unchanged sinde the Paleozoic. They and the Pycnogonida are the only marine arachnids. They are also the only Arachnida with

compound eyes. The chelicerae are

chelate and the pedipalps look like walking legs. But there is four pair of true walking legs. The abdomen has well developed appendages

that have been modified into book gills. Horseshoe

crabs are of course a misnomer as they are not mollusks. Their blood, which is blue in color, is high

in metallic copper and is harvested regularly for medical research. See Inv148 & Inv149 for examples: Subphylum: Myriapoda,

Class: Chilopoda includes the centipedes.

They are dorso-ventrally flattened.

Their body consists of a head and trunk but there is no thorax nor

abdomen. The head bears one pair of

antennae, one pair of mandibles, one pair of maxillipedes with poison

glands at the bases and ducts leading to pointed tips (Note: these are absent in the Diplopoda). There are two pairs of simple eyes called pseudocompound eyes. They have maxillae on the 1st and 2nd

segments. The trunk bears uniramous

appendages and there are 15 to 175 segments.

See examples at Inv141. Body

Wall -- This consists of a cuticle, muscles and a haemocoel Digestive Tract -- A typical mouth

to anus arrangement. Circulatory System -- The heart is

tubular with one pair of ostia per segment.

The blood does not

carry oxygen Respiration -- The tracheae are

lined with ectoderm and cuticle, and heavy rings of cuticle line them. They branch out and ultimately reach all

tissues of the body. The blood does

not have an oxygen carrying function. Excretion -- Malpighian tubules are long, thread-like and blind-ending

tubules. They lie in the haemocoel

and empty into the digestive tract at the junction of the mid and

hindguts. They extract nitrogenous

wastes from the blood. Nervous System -- This system is the

same as that found in the Crustacea. Reproduction -- The sexes are

separate. Genital organs are found at

the posterior end of the body and development is direct. Locomotion -- These animals are fast

movers. Long posterior legs are

sensory and used when moving backwards. Food & Digestion -- Chilopoda

are carnivorous and their food is paralyzed first by the maxillipedes. MEDICAL

IMPORTANCE OF THE ARACHNIDA The Arachnida

are divided into about nine orders with six of these being primarily of

medical importance (Matheson 1950).

One group, the Acarina, is most encountered (See: Tick Borne Diseases). The other five orders do contain species

that have poison glands, and their bites or stings can be of such severity as

to require medical attention. Some species are vectors of pathogenic agents

(Matheson 1950) and Medical Entomology. Table 1. Tick Species That Inflict Harmful Bites

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = Key References: <medvet.ref.htm> [Additional references may be found at:

MELVYL Library] Brumpt, E. 1927. Précis de

paraaitologie. 4th ed. Paris, France. Davis, G. E. 1942. Tick vectors and

life cycles of ticks. IN: Symposium on relasping fever in the

Americas. Amer. Assoc. Adv. Sci. Pub. 18:

67-76 Dunlop, J. A. &

M. Webster. 1999. Fossil evidence, terrestrialization and arachnid phylogeny.

J. Arachnol. 27: 86-93. Harvey, M. S. 2002.

The neglected cousins: What do we know about the smaller Arachnid

orders? Journal of Arachnology 30(2): 357-372. Harvey, M. S. 2007.

The smaller arachnid orders: diversity, descriptions and distributions

from Linnaeus (1758 to 2007). Pages 363-380 in: Zhang, Z. Q. & W. A.Shear

(eds.) Linnaeus Tercentenary: Progress in Invertebrate Taxonomy.

Zootaxa 1668: 1–766. Harvey, Mark S. 2002.

The neglected cousins: what do we know about the smaller arachnid

orders?. J. Arachnol. 30(2): 357-372. Mail, G. A. & J.

D. Gregson. 1938. Tick paralysis in British Columbia. J. Canad. Med. Assoc. 39: 532-537. Matheson, R. 1950. Medical Entomology. Comstock Publ. Co, Inc. 610 p. Nuttall, G. H. F.

1908. The Ixodoidea or ticks,

spirochaetosis in man and animals, piroplasmosis. Harben Lectures. J. Roy

Inst. Pub. Hlth, July, Aug, Sept. Patton, W. S. & F.

W. Cragg. 1913. A textbook of medical entomology. Calcutta & London. Patton, W. S. & A. M. Evans. 1929-1931. Insects, ticks, mies and venomous animals of medical and

veterinary importance. Part I. Medical; Part 2, Public Health. Croydon, England. Service, M. 2008.

Medical Entomology For Students.

Cambridge Univ. Press. 289 p Shultz, J. W. 1989.

Morphology of locomotor appendages in Arachnida - evolutionary trends

and phylogenetic implications. J. Linn. Soc. 97: 1-56. Shultz, J. W. 1990. Evolutionary morphology and

phylogeny of Arachnida. Cladistics 6: 1-38. Shultz, J. W. 1994. The limits of stratigraphic evidence

in assessing phylogenetic hypotheses of recent arachnids. J. Arachnol. 22:

169-172. Shultz, J. W. 2007.

A phylogenetic analysis of the arachnid orders based on morphological

characters. Zoo. J. Linn. Soc. Zoological 150(2): 221–265. Starobogatov, Y. I. 1990.

System and phylogeny of Arachnida (analysis of morphology of paleozoic

groups) [Russian]. Paleontologicheskii Zhurnal 24: 4-17. Weygoldt, P. & H. F. Paulus. 1979.

Untersuchungen zur Morphologie, Taxonomie und Phylogenie der

Chelicerata. 1. Morphologische

Untersuchungen.. Zeit. für Zool. Syst. u. Evolutionsforschung 17:

85-116. Weygoldt, P. 1998.

Evolution and systematics of the Chelicerata. Exptal. & Appl.

Acarol. 22: 63-79. |