File: <miscpoisonous.htm> <Medical

Index> <General Index> Site Description Glossary <Navigate

to Home>

|

POISONOUS & IRRITATING ARTHROPODS (Contact) Please CLICK on

underlined links & photos for

details:

There are many records dating back to the 1800's of

arthropods injuring and/or inflicting poisons when in contact with humans and

other animals. Their mere presence

may cause irritations and allergic responses. Matheson (1950) is one of the few medical entomology authors

who has presented detailed information on this subject. He noted that secretions of the salivary

glands of arthropods when entered into body wounds can prevent blood

coagulation that can cause hemolysis, produce paralysis or act as

irritants. Also, when insects draw

blood there is always the possibility that the proboscis may contain

pathogens, which if entering the blood stream serious health problems can

result. Disinfections of such wounds

is highly recommended. Order: Scorpiones (Scorpionida) -- scorpions: These animals have a well marked

cephalothorax and segmented abdomen that is equipped with a sting and poison

gland at the posterior end. They can

be dangerous in warmer regions.

Chelicerae and pedipalps are both chelate. They have book lungs.

They feed on other arthropods.

They are also viviparous as they bear living young. See Inv150 & Inv151 for examples: Some arthropods use venom as a weapon to kill or paralyze

when they are threatened. Humans

frequently encounter wasps, bees, ants, arachnids, millipedes or centipedes,

etc. that may attack especially if nesting sites are threatened. Their trailing abdomen that is equipped

with a sting easily identifies large arthropods such as scorpions (See: Scorpion). Scorpions are especially common in

tropical and subtropical areas where some species can attain almost a food in

length. The sting can be very painful

but rarely is it fatal. However, one

species in Mexico, Centruroides suffusus

Pocock, has been a threat especially to young children, with death ensuing

rapidly after a sting. The stings of

yellow jacket wasps and Africanized bees defending their nests not

infrequently kill full-grown humans. Class: Arachnida: Order Araneae includes the true

spiders. Segmentation is obscure in

the abdomen and there are no obvious appendages except 3-4 pairs of

spinnerets at the posterior end of the abdomen that are modified abdominal

appendages. Several examples of

spiders may be seen in the following diagrams Inv143 - Inv147: Although spiders are generally feared they do not bite

readily, but they all possess poison glands and the bites of some species can

cause severe irritation and even tissue destruction. The Black Widow spider, Latrodectus mactans

Fab. is common in warmer parts of the temperate zone

where fatalities sometimes result from its bite. It is easy to recognize by a jet-black color, a hourglass

pattern on the underside of its abdomen and a web that is irregular and

without pattern. Matheson (1950)

described the symptoms from the bite as "acute pain, localized and

general, profuse perspiration, restlessness, nausea, vomiting, labored

breathing and constipation.:" In

tropical areas other species of Latrodectus

are considered very dangerous. The Brown Recluse or "Violin" spider, Loxosceles

reclusa, like the black widow, has venom that causes necrosis

of body tissues, which may require drastic surgical removal of the area

around the bite. The common name,

"violin spider"

refers to a marking on the top of the cephalothorax that resembles a violin. Another species that has spread to other parts of the

world is the Mediterranean Recluse spider, Loxosceles

rufescens (Dufour). Also,

the Desert Recluse spider, Loxosceles

deserta Gertsch occurs in the southwestern United States, where

its preference for wild habitats generally keeps it away from human

habitation. Another group of spiders, the Tarantulas (Avicularia spp.), have large species

with a hairy appearance that tends to frighten people and animals (See: Avicularia sp.). Myths about their ferociousness were

rampant during the Middle Ages.

However, they are quite tame if not provoked (Baerg 1923) and can even

be trained as pets. Tarantulas are

abundant in tropical areas, but they extend well into the Temperate Zone.

They are especially active at night as in the Ozark Region of Arkansas,

United States where large numbers can crawl all over sleeping campers, but

without inflicting bites. Subphylum: Myriapoda, Class: Chilopoda includes the centipedes. They are dorso-ventrally flattened. Their body consists of a head and trunk

but there is no thorax nor abdomen. The

head bears one pair of antennae, one pair of mandibles, one pair of

maxillipedes with poison glands at the bases and ducts leading to pointed

tips (Note: these are absent in the

Diplopoda). There are two pairs of

simple eyes called pseudocompound eyes.

They have maxillae on the 1st and 2nd segments. The trunk bears uniramous appendages and

there are 15 to 175 segments. See

examples at Inv141. Centipedes are also frightening to behold and have caused

undue alarm, They possess poison glands although they rarely bite and if so

the venom is not very toxic, serving primarily for food digestion. They are recognized by their many legs on

a long body with a distinct head and a pair of many jointed antennae (See: Scolopendra obscura). Most species are terrestrial, preying on

small animals in dark places under logs, leaves and stones (Matheson

1950). Subphylum:

Myriopoda, Class: Diplopoda includes the millipedes. These are cylindrical animals with a head

and trunk that is the same as in the Chilopoda. The head appendages include antennae, mandibles, one pair of

maxillae (instead of 2 pair as in the Chilopoda) and pseudocompound eyes on

the head. The trunk has 25-100 or

more segments with each segment bearing two pair of appendages. A fusion occurs between two segments all

along the body except on the first trunk segment. See example at Inv142. Millipedes are terrestrial arthropods with a wormlike

appearance and many small legs (See: Millipede).

They have a distinct head with the next four segments being their

thorax. The remaining segments each

bear two pairs of legs. There are no

poison glands on their mouthparts, but many species have glands on some

segments that produce an irritating liquid, which they can eject for some

distance. This liquid is an irritant

that can cause blindness if reaching the eyes (Burtt 1947). There are also insects that have special hairs, which can

cause irritation or allergic reactions (See:

Io Moth & Browntail

Moth). Some caterpillars of moths

and beetles have structures that cause considerable irritation. Matheson (1950) lists the following

Lepidoptera families that belong to this group: Eucleidae, Megalopygidae, Saturniidae, Thaumetopoeidae, Arctiidae, Noctuidae and

Nymphalidae. The irritation comes

from special spines or barbed hairs that have poison glands. The barbs can penetrate skin and the

poison will spread to produce a rash.

Gilmer (1925) distinguishes two types of poison gland hairs or setae

as primitive and modified. The

primitive type has a single seta with a gland cell that opens directly

through a pore canal into the hollow of the seta. The seta contains the poisonous secretion of the gland

cell. These setae retain their

urticating properties long after the caterpillar sheds them and their

efficacy is not affected by drying.

The modified hair type is found among caterpillars of the Lymantriidae

and some Thaumetopoeidae (e.g, brown-tail moth Euproctis phacorrhoea). Other minute structures occur on

caterpillars that can produce rashes.

Matheson (1950) listed a some of the more important caterpillars that possess urticating

structures: URTICATING CATERPILLARS (List derived from Matheson 1950)

Coleoptera

include the beetles that have biting mouthparts; the fore wings are modified

to form firm elytra. The hind wings

are membranous and folded beneath the elytra, and they are usually reduced or

absent. The prothorax is large and

the mesothorax is greatly reduced.

They have complete metamorphosis.

The larvae are campodeiform or eruciform or generally apodous. Some beetles that belong to the families Meloidae and

Staphylinidae can also cause bodily irritation. The Meloidae, or "Blister

beetles" have cantharidin in their body fluids. The extract has been used in small amounts

as a diuretic and a stimulant to the urinary and reproductive organs. Blister beetles populations can assume

large numbers and do considerable damage to plant foliage. The Staphylinidae,

or "Rove beetles", have a

genus, Paederus in which there

are species that cause blisters if crushed on the body. Problematic species are Paederus fuscipes (Orient), P. sabaeus (South Africa), P. cribripunctatus (East Africa), P. peregrinus (Java), P. amazonicus and P. columbinus (Brazil), and P. irritans (Ecuador) (Matheson

1950). The resulting blisters are

often slow to heal, so it is best to avoid handling both groups if

possible. However, the benefits

derived from staphylinids serving as predators of other harmful insects may

outweigh their harmful effects (Moore

& Legner 1973) The Apocrita of the order Hymenoptera are

included here. The second abdominal segment is constricted to form a narrow

waist or petiole, the first segment being firmly joined with the thorax. Larvae are apodous when full-grown. Ichneumon flies have slender curved antennae,

and there is a stigma on the wing. The ovipositor is generally long and

projects forward from the tip of the abdomen. The larvae of Lepidoptera and

of sawflies are their usual hosts. Insects that have an ability to sting their prey and

humans, belong primarily in the order Hymenoptera, which includes the bees

and wasps. Families of the order

usually involved are Apidae (including Bombidae), Vespidae, Sphecidae,

Mutillidae and Formicidae. In the

honeybee the female workers have a sting with sufficient poison to inflict

considerable pain, even though a bee deploying the sting results in its

death. The hybridization of an

African with an Italian strain of honeybee has produced a viscious hybrid,

resulting in the death of people in the Americas (See: Africanized bees) The stings of hornets, bumblebees

and wasps are equally potent although the insect does not die after an

attack, but can continue to sting repeatedly. There are many deaths annually among humans and animals that

can be attributed to stingings from wasps especially. The ants

exist as many species and they are numerically very abundant. Polymorphism is pronounced. The various social orders in the family

have developed around a caste system.

This includes a queen, workers, soldiers, etc. The workers can appear in different shapes

and forms as influenced by nutrition and care among individuals of the

colony. All of the workers are

wingless. Some ants, such as the fireant, whose stings are very potent,

especially if administered by large numbers in an ant colony. The ponerine ant, Paraponera clavata Fab., of South

America will attack if disturbed, inflicting severe stings (Bequaert 1926). The abdomen

in this group is rather soft and able to take on a great deal of food, which

other members of their colony are able to solicit. They obtain it by stroking the bearer who then regurgitates the

food. Colony

Establishment. -- New males and females in the colony develop wings, after

which they swarm and mate. The

females fall to the ground and chew off their wings, while the males

dies. The female then finds a

suitable place to construct a cell into which she will lay eggs. While waiting for the eggs to hatch, the

female does not feed. She derives

nourishment by absorbing internal body parts, such as wing muscles, etc. Some species

such as the driver and army ants are nomadic. Conspicuous nests in the ground may be 2.7 meters or more below

the surface. Ants also may live in

oak acorns, dry stems, etc. Their

food includes seeds, dead insects, aphid honeydew and household foods. They may even take aphids into their nests

for the winter where they are attended. Ant control

in houses is possible with poison bait traps. The treatment of concrete foundations with insecticides is a

more drastic approach. Allergies of varied intensity are associated with the

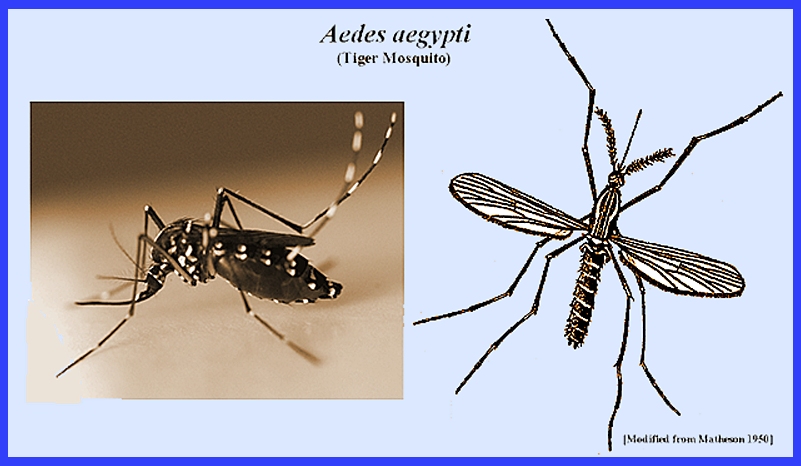

encounter of many different kinds of insects. Prolonged exposure to the allergen, such as in the bite of Aedes aegypti,

can result in immunity to its effects (McKinley 1929). Some people with special skin properties

are also little affected by some mosquitoes.

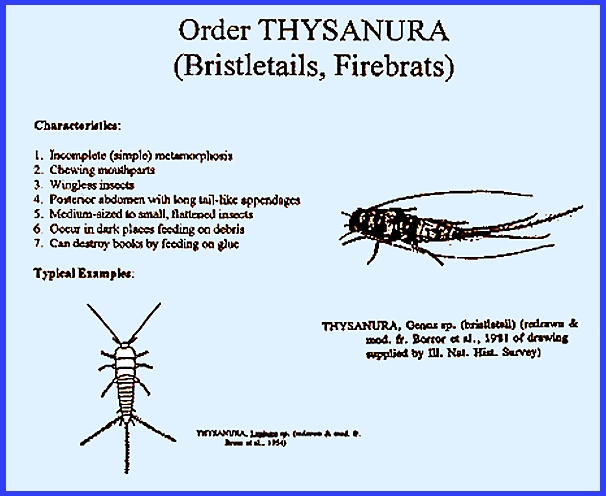

Serious reactions of a prolonged rash can result from exposure to

insects that are generally considered harmless, such as occurs with some

species in the primitive Thysanura order of bristletails and silverfish

(See: Thysanura)

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = Key References: <medvet.ref.htm> Baerg, W. J. 1922. Regarding the habits of tarantulas and the effects of their

poison. Sci. Mon. 1`4: 482-89. Baerg, W. J. 1923.

The black widow; its life history and the effects of its poison. Sci. Mon. 17: 535-47. Baerg, W. J. 1924.

The effect of the venom of some supposedly poisonous arthropods. Ann. Ent. Soc. A.er

17: 343-52. Benson, R. L. &

H. Semenov. 1930. Allergy in relation to bee sting. J. Allergy 1: 105-16. Bequaert, J. C. 1926.

Medical report of Rice-Harvard expedition to the Amazon. Cambridge Univ., Mass. Beyer, G. F. 1922.

Urticating and poisonous caterpillars. Quart. Bull. La. St. Bd. Health 13: 161-68. Burtt, E. 1947.

Exudates from millipedes with particular reference to its injurious

effects. Trop. Dis. Bull 44: 7-12. Chamberlain, R. V. &

W. Ivie. 1935. The black widow spider (Latrodectus mactans) and its varieties

in the United States. Univ. of Utah

Bull. 25. Comstock, J. H. 1940.

An Introduction to Entomology,

9th Rev. ed. Comstock Publ. Co., Inc.,

Ithaca, New York. 1064 p. Cornwall, J. W. 1916.

Some centipedes and their venom.

Ind. J. Med. Res. 31: 541-57. De Villiers, P.

C. 1987. Simulium

dermatitis in man: clinical and

biological features in South Africa.

So. Afr. Med. J. 71: 523-25. Ewing, H. E.

1928. Observations on the

habits & injury caused by bites or stings of some common North American

arthropods. Amer. J. Trop. Med. 8: 39-62. Gilmer, P. M. 1925.

A comparative study of the poison apparatus of certain lepidopterous larvae. Ann. Ent. Soc. Amer. 18: 203-39. Hoffman, C. C. & L. Vargas. 1935.

Contribuciones y conocimiento de los venenos de los alacranes

mexicanos. Bol. Inst. Hig. Mex.

2(4): 182-93. Legner, E.

F.

1995. Biological

control of Diptera of medical and veterinary importance. J. Vector Ecology 20(1): 59-120. Legner, E. F. 2000.

Biological control of aquatic Diptera. p. 847-870.

Contributions to a Manual of Palaearctic Diptera, Vol. 1, Sci. Herald, Budapest. 978 p. Matheson, R. 1950. Medical Entomology. Comstock Publ. Co, Inc. 610 p. McKinley, E. B. 1929.

The salivary gland poison of the Aedes

aegypti. Proc. Soc. Exp.

Biol. Med. 26: 806-809. Mills, R. G. 1923. Observations on a series of cases of dermatitis caused by a

liparid moth, Euproctis flava

Bremer. China Med. J. 351-71. 106. Moore, I. & E. F. Legner. 1973.

Beneficial insects: neglected

"good guys." Environment

Southwest 454: 5-7. Norman, W. W. 1896.

The poison of centipedes, Scolopendra

morsitans. Proc. Texas

Acad. Sci. pp. 118-19. Parlato, S. J. 1929. A case

of coryza and asthma due to sand flies (caddis flies). J. Allergy 1: 35-42. Pavlovsky, E. N. 1927.

The cutaneous poison of the beetle, Paederus

fuscipes. trans. Roy. Soc.

Trop. Med. Hyg. 20: 450-51. Roche, A.J., N.A.

Cox, L.J. Richardson, R.J. Buhr, J.A. Cason, B.D. Fairchild, and N.C.

Hinkle. 2009. Transmission of Salmonella to Broilers by Contaminated Larval and Adult

Lesser Mealworms, Alphitobius diaperinus

(Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). Poultry Science 88: 44-48. Service, M. 2008.

Medical Entomology For Students.

Cambridge Univ. Press. 289 p Smithers, R. H. N. 1944.

Contributions to our knowledge of the genus Latrodectus in South Africa. Ann. So. Afr. Mus. 36:

263-313. Tyzzer, E. E. 1907. The pathology of the brown-tail dermatitis. J. Med. Res. 16: 43-64. Verbeek, F. A. T.

H. 1930. De

Canthariden op Java. Tectona 23: 304-08. Verbeek, F. A. T. H. 1932.

De ontwikkelings-stadia Van Mylabris

en epicauta in de tropen. Tijdschr. v. Ent. 75

(Sup.): 163-69. Vetter, R.S., N.C. Hinkle, and L.M.

Ames. 2009. Distribution of the Brown Recluse Spider (Araneae: Sicariidae)

in Georgia with Comparison to Poison Center Reports of

Envenomations. J. Med. Entomol. 46(1): 15-20. Walsh, D. 1924.

Insect bites and stings. J.

Trop. Med. & Hyg. 27: 25-26. Wilson, W. H. 1904.

On the venom of scorpions. Records

of the Egyptian Government School of Medicine, Cairo 2: 7-44. |