File: <culicidaemed.htm> <Medical Index> <General Index> Site Description <Navigate

to Home>

|

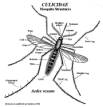

Arthropods: Diptera CULICIDAE (Contact) Please

CLICK on

underlined links to view: [Also See: <Culicidae Key>] Nematocera =

"long antennae."

Anophelinae-- Anopheles spp. The

wings are spotted with definite patches of scales. Their feeding position is at a 45-degree

angle with the surface.

The aquatic larvae feed horizontal with the water film due to short

terminal spiracles (See Photo). Members of the genus are the sole

vectors of malaria. They have long

palpi and the eggs are laid singly. Culicinae -- Aedes, Coquillettidia, Culex spp. Haemagogus, Mansonia, Psorophora, Sabethes, The wings are not spotted and mostly entirely clear. The feeding position angle is primarily horizontal with the

surface. The aquatic larvae have

developed an elongated siphon and feed hanging down from the water surface at

an angle. Members of the genus

include the common pest mosquitoes, which carry many viruses such as Yellow

Fever, Dengue, Encephalomyelitis and the

Filarial Worm. They have short palpi and the eggs are laid in masses. There is

disagreement about the number of genera in the subfamily, but Service (2008)

listed 38 genera, assigning some to subgenus status. Of primary medical importance are Culex, Aedes,

Haemagogus, Sabethes and Mansonia, with Coquillettidia

and Psorophora of lesser

importance. Culex, Aedes

and Coquillettidia are found

both in tropical and temperate climates while Psorophora are found only in the Americas with a wide

distribution over many climates. Sabethes and Haemagogus are found only in Central and South America

with Mansonia occurs in

tropical portions only. Service

(2008) noted that members of the Aedes

genus are vectors of Yellow Fever

in Africa, while Aedes, Haemagogus and Sabethes are vectors of Yellow Fever

in South and Central America. Some Aedes vector Dengue Fever, and all Culicinae may vector other

arboviruses. Some Culex, Aedes

and Mansonia are also vectors

of Filariasis caused by Wuchereria bancrofti and Brugia malayi. Although some Psorophora

vector arboviruses, most species are mainly annoying pests. Coquillettdia

crassipes vectors Brugian Filariasis. Culex spp. Biology Many

different aquatic habitats are chosen for oviposition onto rafts that float

on the water. The Culex species tend to choose shallow

habitats such as ditches, ricefields and temporary puddles, with even small

containers and tree holes being adequate.

Culex quinquefasciatus,

the vector of Bancroftian Filariasis chooses polluted

aquatic habitats containing rotting organic debris. Service (2008) noted that the larvae of this species also occur

in ditches, blocked drains, septic tanks, etc. containing polluted water, and

that it has adapted well to urbanization.

The adults are especially active after sundown. Culex tritaeniorhynchus,

the vector of Japanese Encephalitis, chooses

ricefields, polluted fish ponds and puddles containing vegetation. Other species

of Culex, such as Cx. quinquefasciatus,

bite during nighttime and may rest indoors as well as outside of dwellings.

Many Aedes

species in warm climatic areas choose restricted containers to oviposit, such

as tree holes, small pools, tires, barrels, cans, etc. Service (2008) noted that Aedes aegypti breeds in

water-storage containers both inside and outside of dwellings. The larvae require uncontaminated water

for development. Aedes africanus, a vector of Yellow

Fever, breeds in tree holes and bamboo while Aedes bromeliae also a vector of Yellow

Fever, chooses leaf axils of banana, pineapple, etc. The vector of Dengue, Aedes albopictus, prefers

natural and container habitats.

Vectors of Filariasis, Aedes

polynesiensis and Ae.

pseudoscutellaris, develop in coconut shells or tree holes and

bamboo. Aedes togoi,

also a vector of Filariasis,

prefers pools of fresh water among rocks. Other Aedes species in colder climatic areas

prefer pools formed from melting snow and marshlands.

Aedes mosquitoes are able to complete

their development in only 7-12 days, depending on temperature. They are usually active in daytime and

rest outdoors. Haemagogus spp. Biology Mosquitoes of

the Haemagogus genus are restricted

to South and Central America. Their

eggs tolerate desiccation, and oviposition and larval development are

primarily in tree holes and bamboo, but also in rock pools, coconut shells

and occasionally in containers. But

they are typically forest dwellers.

The adults are active during the day feeding on simians in tree

tops. However, they may descend to

the ground during lumbering operations to attack humans. Several species, such as Haemagogus spegazzinii, Hg.

leucocelaenus and Hg.

janthinomys are vectors of Yellow Fever

(Service 2008). Sabethes spp. Biology Sabethes mosquitoes

are also restricted to South and Central America. Oviposition is in tree holes, bamboo and bromeliads, etc. They are also forest dwellers, which are

active during daytime primarily in tree canopies. However, they will also descend when forced to by logging

operations. Sabethes chloropterus

is a vector of Yellow Fever. Mansonia spp. Biology Most species

of Mansonia

occur in tropical climates, with only a few being found in temperate

regions. Oviposition is on the

undersurface of vegetation where the eggs are glued. The eggs can tolerate desiccation. The larvae develop in permanent water that

contains vegetation such as marshes and swamps. Irrigation canals with vegetation are also suitable. The larvae

and pupae remain attached to plants but will leave if disturbed, but they are

difficult to detect. Most adults are

active at night, with a few species also active during the day. Service (2008) reported that the medical

concern is for Mansonia vectors of Filariasis,

and rarely of some mild arboviruses. Coquillettidia

spp. Biology Mosquitoes of

the Coquillettidia

genus are of minor medical importance in the tropics but only occasionally in

temperate climates. Their eggs are

formed onto rafts that float like the Culex

species. The larvae are similar to Mansonia. Coquillettidia crassipes

is a vector of Filariasis. Psorophora spp. Biology Psorophora mosquitoes,

which range throughout the Americas, are also of minor medical

importance. Like Aedes their eggs tolerate

desiccation. Oviposition is in rice

fields and flooded pastures. There

are a few vectors of arboviruses, such as Venezuelan

Equine Encephalitis, and Yellow Fever. Their importance is mainly as vicious

biters (e.g. Psorophora ciliata, Ps. columbiae, Ps. cyanescens, Ps. ferox #1 & #2) = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = Key References: <medvet.ref.htm> <Hexapoda> [Additional references may be found at: MELVYL Library ] Bock, G. R. & G.

Cardew. 1996. Olfaction in Mosquito-Host

Interactions. Chichester: Wiley

Publ., England Carpenter & Lacasse.

1955. Mosquitoes of North America. Clark, G. G.

1994. Prevention of tropical

diseases: status of new and emerging vector control strategies. Proc. Symp. Vector Control, Amer. J. Trop. Med. & Hyg. 50(6): 1-159. Clements, A. N. 1992.

The Biology of Mosquitoes. Vol. 1:

Development, Nutrition & Reproduction, Chapman & Hall, London. Curtis, C. F. 1989.

Appropriate Technology in Vector Control. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida. Foster, W. A. & E.

D. Walker. 2002. Mosquitoes (Culicidae). IN: Med. &

Veterinary Ent.. Acad. Press, Amsterdam.

pp. 203-62. Matheson, R. 1950. Medical Entomology. Comstock Publ. Co, Inc. 610 p. Service, M. 2008.

Medical Entomology For Students.

Cambridge Univ. Press. 289 p Legner, E. F. 1995.

Biological control of Diptera of medical and veterinary

importance. J. Vector Ecology 20(1):

59-120. Legner, E. F.. 2000.

Biological control of aquatic Diptera. p. 847-870.

Contributions to a Manual of Palaearctic Diptera, Vol. 1, Sci. Herald, Budapest. 978 p. Pates, H. & C. Curtis. 2005. Mosquito behavior and vector control. Ann. Rev. Ent. 50:

53-70. Spielman, A. &

M. d'Antonio. 2001. Mosquito: a Natural History of Our Most

Persistent and Deadly Foe. Faber

& Faber, London. |

FURTHER DETAIL = <Entomology>, <Insect Morphology>, <Identification Keys>