Donald M. Wilson

~ the point that must

be reached ~

(1932

- 1970)

©

Scott N. Currie, UC Riverside, 2011

Don Wilson was

a pivotal figure in the emergence of neuroethology as a discipline,

and in the use of invertebrate “simple systems” for neuro-behavioral

research in the 1960s. He remains especially well known for his first locust

flight paper (Wilson, 1961a) that conclusively demonstrated the existence of a

flight "central pattern generator" (CPG) – a central neural network that could produce rhythmic, patterned

motor activity on its own, even when deprived of all movement-related sensory

feedback. His

studies laid the groundwork for later cellular and synaptic analyses of the

flight circuit by Malcolm Burrows (e.g., 1975), Robertson and Pearson (e.g.,

1985) and others that produced a finely detailed understanding of locust flight's

intricate neural mechanism. Wilson pioneered this work as a

postdoctoral fellow in Denmark and continued it as faculty at Yale, U.C. Berkeley and

Stanford. But before all this, while he was still a student, Wilson was also a highly accomplished rock climber.

He

is remembered in that community for numerous first ascents in the American

southwest, including Tahquitz in southern California and several sandstone

towers in the "Four Corners" region of the Colorado plateau. He

died in June 1970 during a whitewater rafting accident in Idaho at the age of

37. W.

Jackson Davis has a hand-written note from Don Wilson, framed on the wall of his

home-office. It’s a Kafka aphorism

(from: The Zurau Aphorisms, #5) that was found on Wilson’s

desk at Stanford shortly after his death was announced. It reads:

“From a certain point onward there is no

longer any turning back. That is the point that must be reached.”

[Earlier versions of this brief biography were presented

in the March

2011 issue of Neuroethology Newsletter and in a history

poster at the 2010 Society for Neuroscience conference.]

Early

scientific

training

Donald

Melvin Wilson was born in Seattle on October 6, 1932 and spent all of his early

life in southern California, graduating from John C.

Fremont high school in south Los Angeles in 1950,

receiving his BS and MS degrees in biology from USC in 1954 and 1956,

respectively, and his Ph.D. in zoology from Theodore

Bullock’s laboratory at UCLA in 1959. (All dates provided by Nancy Wilson;

birth date confirmed from Don Wilson's draft card. The 1933 birth date

originally cited in Wilson's

Stanford obituary was incorrect.) His doctoral thesis was entitled “Nervous control of muscle in Annelids

and Cephalopods” and helped to establish his reputation as a promising young

comparative neurobiologist when it was published as back-to-back papers in the

Journal of Experimental Biology (Wilson, 1960a,

b). This research focused on motor

control in two groups of annelids (polychaetes and leeches) and two of

cephalopods (octopi and squid), and included observations on the muscular

effects of giant axon stimulation in polychaetes (Neanthes brandti and N. virens

Sars) and squid (Loligo pealeii and L.

opalescens

Berry).

The work was conducted at UCLA during the academic year, and at the

Marine Biological Lab in Woods Hole (L.

pealeii experiments) and the Friday Harbor Marine Lab (N.

brandti) during the summers of 1957 and 1958, respectively.

Wilson

extended

that interest in giant axon function in two additional papers that were not part

of his thesis. These included (1)

one of the earliest studies to correlate Mauthner cell activity with fish

startle behavior (Wilson, 1959; using the African lungfish, Protopterus

because of the huge size of its Mauthner axons) and (2) an account of the

electrical connections between lateral giant fibers in the earthworm (Wilson,

1961b). On all four of these papers,

Wilson

was sole

author, which speaks to his drive and self-direction, but also recalls Ted

Bullock’s unselfish encouragement of independence in all his students.

Central

pattern generation in the control of locust flight

After

finishing his Ph.D., Wilson

moved to Torkel

Weis-Fogh’s lab in Copenhagen

for

post-doctoral work (Sept. 1959 - Oct. 60), where he began his locust flight

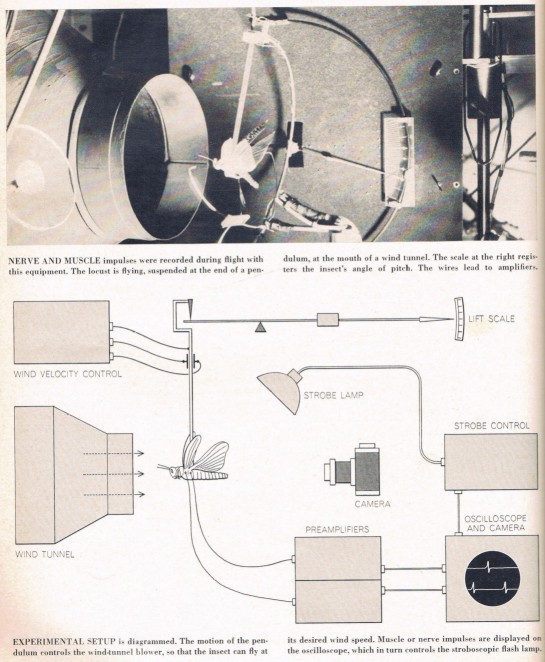

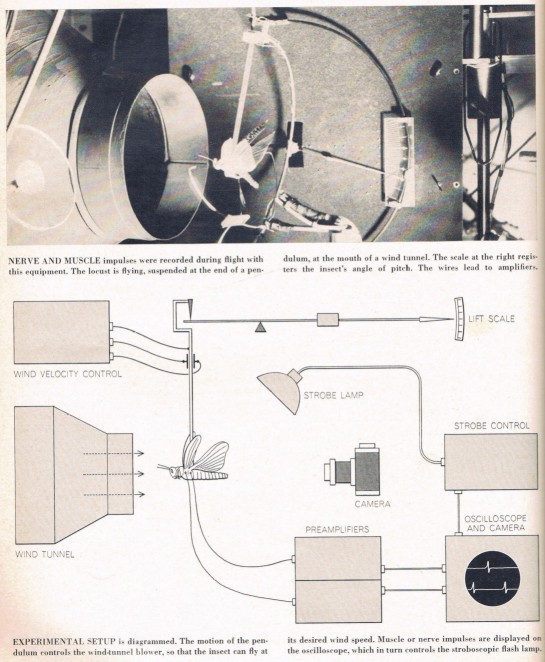

experiments. He used an ingenious

setup (see below) which permitted the

synchronization of wing muscle or nerve recordings with stroboscopic

photographic records of wing position during flight.

The insects flew in-place, suspended at the end of a pendulum in front of

a wind-tunnel. The other end of the

pendulum acted as the arm of a double-throw switch that controlled the wind

velocity via a servo-mechanism, so that the strength of the animal’s forward

flight controlled wind speed.

Experimental apparatus used by Wilson (1961a) to record wing position

along with sensory nerve and muscle impulses during tethered locust flight.

Wing muscle action potentials triggered a strobe lamp, which captured

wing position via a camera with an open shutter and permitted synchronization of

wing-position with nerve/muscle activity (from Scientific

American,

Wilson, 1968.)

Portrait

of Torkel

Weis-Fogh at Cambridge University, 1969. The original hangs in the Cambridge

University

Zoology (Balfour & Newton)

Library, and is used with their permission (Ramsey & Muspratt / Cambridgeshire Collection).

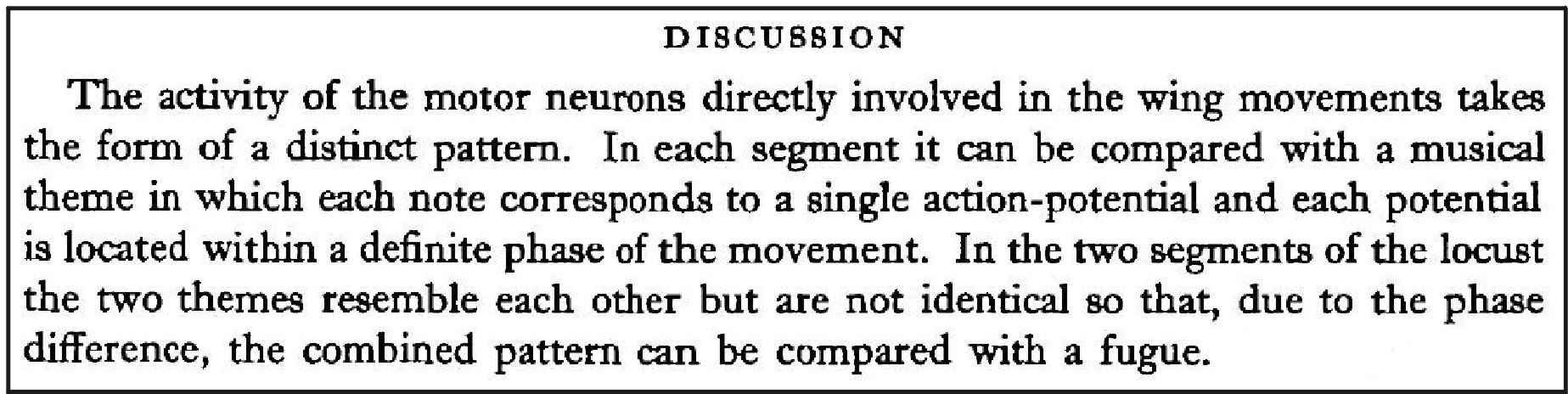

From:

Wilson and Weis-Fogh(1962)

The

essential result of Wilson’s 1961

JEB paper was that the basic flight motor pattern remained intact following

partial or complete deafferentation of the wings, showing that movement-related

sensory feedback was not necessary for the construction of normal motor

patterns, and indicating the existence of a central pattern generator for

neurogenic flight in the locust. This

was at a time when Sherrington’s “chain-reflex”

hypothesis for motor pattern generation, in which simple sensory reflexes

triggered each other sequentially to form complex motor patterns (Sherrington,

1947; p.182), was still widely favored (Hoyle, 1980; Bullock, 1995; Edwards,

2006; Stuart, 2007; Mulloney and Smarandache, 2010).

After returning from Copenhagen, faculty

appointments followed at Yale (Oct. 1960 – Aug. 61), UC Berkeley (Sept. 1961

– June 68), and Stanford (July 1968 – June 70). The term “central pattern

generator” (actually, “central nervous pattern generator”) was coined in another significant

paper written with one of Wilson’s early

graduate students at UC Berkeley, Robert Wyman (Wilson and Wyman, 1965.) This

article showed that random or rhythmically timed electrical stimulation of the

thoracic nerve cord in decapitated and wing-deafferented locusts still evoked

coordinated motor output that resembled normal flight motor patterns.

Coordinated flight activity began only after many stimuli, exhibited a

wind-up of cycle frequency over multiple seconds until it reached a constant

level (about 20 Hz), then displayed many cycles of after-discharge following

stimulus-offset. All of these

effects are strikingly similar to the non-linear summation of subliminal stimuli

and prolonged motor after-discharge that Sherrington (1947) described for

hindlimb scratch motor patterns in low-spinal dogs – and suggest a similar

build-up and storage of excitation in a central neural network.

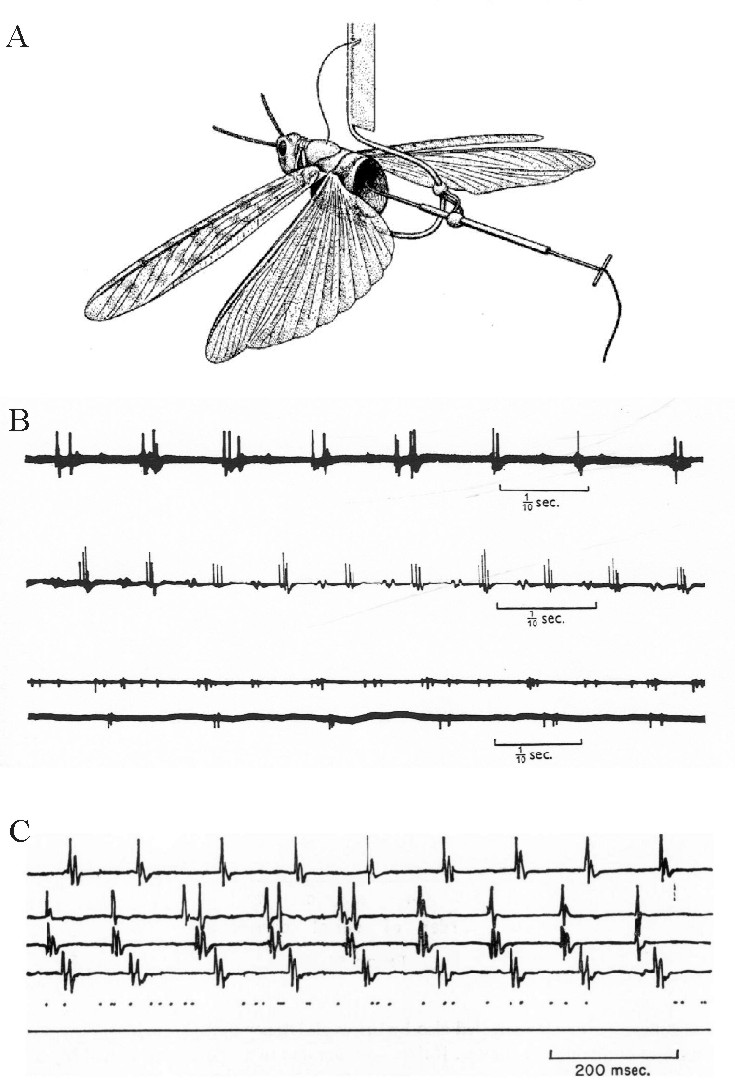

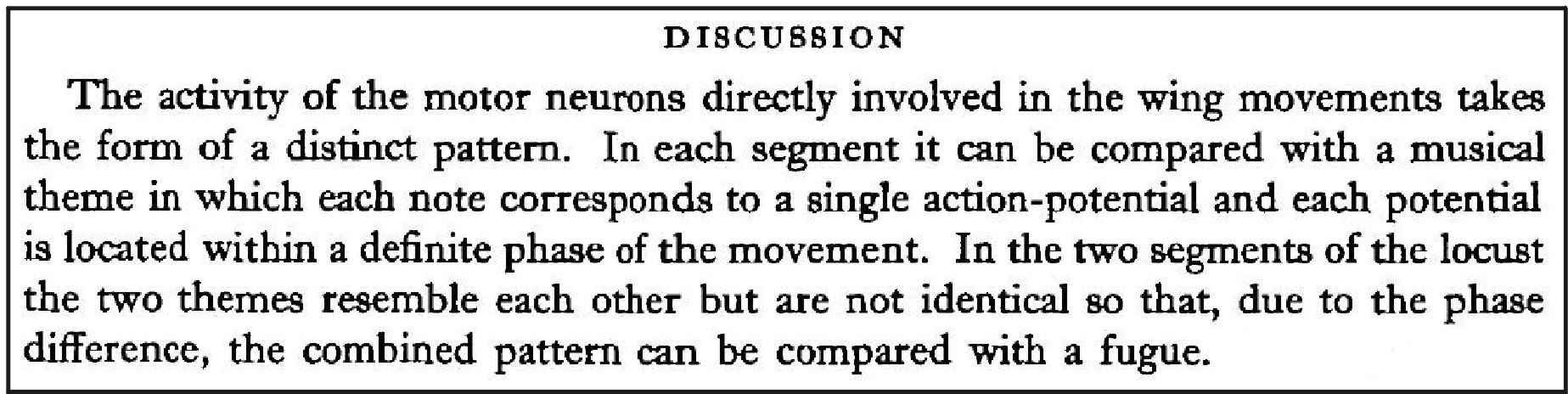

A:

Surgically reduced locust

preparations, with viscera and varying amounts of their body walls removed,

still exhibited wind-induced flight motor patterns, even after movement-related

sensory feedback from the wings was reduced or completely abolished

(Wilson, 1968b)

B: Fictive flight motor patterns recorded from the central stumps of

the metathoracic and mesothoracic nerves in highly reduced locust preparations

in which all sensory feedback from the wings had been eliminated (Wilson,

1961a.)

C: Coordinated flight motor pattern recorded from 4 wing muscles

in a headless preparation in

response to randomly timed electrical stimulation of the ventral nerve

cord,

indicated by dots (Wilson and Wyman, 1965).

Wilson’s relatively brief time at

Berkeley (~6.5 years) also resulted in some of the earliest computational and

analog electronic models of pattern generating neural networks (Wilson, 1966,

Wilson and Waldron, 1968). In addition, there were analyses of neuromuscular control in

myogenic Dipteran flight (Nachtigall and Wilson, 1967), models of interlimb

coordination during 8-legged locomotor

gaits in tarantulas (Wilson, 1967), and elegant studies that assessed the role of

movement-related sensory feedback in modulating centrally driven motor patterns

and compensating for perturbations (Wilson and Gettrup, 1963; Wilson,

1965;

1968a). In one of these papers (Wilson,

1968a), he nicely summarized the complementary roles of the CPG and sensory

feedback in constructing adaptive behavior: "In the

locust flight control system proprioceptive reflexes and exteroceptive inputs

supplement and complement the information built into the CNS. Hence, even though

the ganglia are pre-programmed to produce a nearly normal motor output pattern,

that pattern can be modified to meet current needs. It seems to me that the CNS

has programmed into it through the genetic and developmental processes, nearly

everything that it is possible for it to know before actual flight occurs. The

sensory inputs supply only the genetically unanticipatable information such as

wind direction and position of the horizon." "... Overall

it appears that the flight control system is a very safe one, having a

multiplicity of complementing mechanisms. It is centrally pre-programmed,

perhaps to the fullest extent possible, but it also has a superimposed set of

reflexes which can simultaneously relate the animal to its environment,

compensate for bodily damage, and correct errors in its central programme.

As a result it can tolerate a high degree of damage and still carry out a very

demanding activity."

Rock

Climbing

Wilson

met Frank Hoover and Fred Martin while in high school during a summer intern

program at the LA County Museum of Natural History and the three began

backpacking and climbing together in the Sierra Nevada (Fred Martin, pers.

commun.). He started

rock

climbing more seriously as an undergraduate biology major at USC (Frank Hoover, pers. commun.) and developed in to a world-class climber by

the mid 1950s, when he was in his early twenties.

He is still well known amongst the rock-climbing cognoscenti for a number

of extremely hairy first ascents, with small teams made up of the early hot-dogs

of the sport (Royal Robbins, Jerry Gallwas,

Mark

Powell, Bill “Dolt” Feuerer, Chuck Wilts, Warren Harding).

His records began with several important California climbs in

the early to mid 1950s, including “Open Book” at Tahquitz (Idyllwild, CA;

see

Robbins, 2010: "Fail

Falling") in 1952

and a famous first attempt at the NW face of Half Dome in Yosemite

in 1955

– an attempt that only made it about 1/4 of the way up the sheer wall of rock,

but attracted the interest of the Saturday Evening

Post. During this period, Wilson

also helped devise the YDS (Yosemite Decimal System) with Royal Robbins and

Chuck Wilts, which permitted the precise gauging of difficulty levels for

“free climbs” (without aids) on a 5.0-5.9 scale, and he co-authored the

“Climber’s Guide to Tahquitz Rock” with Wilts in 1956, which detailed the

YDS for the first time. (At the time, Chuck

Wilts was a professor of Electrical Engineering at Caltech and a pioneer in

the fields of electric analog computers and feed-back control systems.) Wilson

remains

best known in climbing circles for his first ascents of several sandstone desert

towers in the “Four

Corners” region

of the southwest. These included “Spider Rock” (March 1956) in Canyon de

Chelly, Arizona, “Cleopatra’s Needle” (Sept. 1956) in

the Valley of Thundering Water,

New Mexico

and the

“Totem Pole” (June 1957) in Monument

Valley, Utah. All these desert spire

climbs occurred during a 15-month period in which

Wilson

finished

his M.S. degree at USC and began full-time work toward his doctorate at UCLA

(Burton, 1956; Wilson, 1957a, 1957b, 1958; Breed, 1958; Sherrick, 1958; Roper,

1970; Jones, 1976; Gallwas, 2007, 2010; Bartlett, 2010). Following the Totem

Pole ascent, the

Desert

Tower

team

(Wilson, Gallwas, Powell, Feuerer) went their separate ways. Don and Nancy

Wilson traveled by VW Bug to Woods Hole, Massachusetts so that Don could spend

the rest of the summer 1957 at the Marine Biological Lab.

After that, he completed his Ph.D. at UCLA with Ted Bullock, then moved

to Copenhagen

to

post-doc with Torkel Weis-Fogh and begin his seminal locust flight studies.

After his return to the United

States

in a

series of faculty positions, he continued to climb for pleasure with friends and

family, but no longer pursued records.

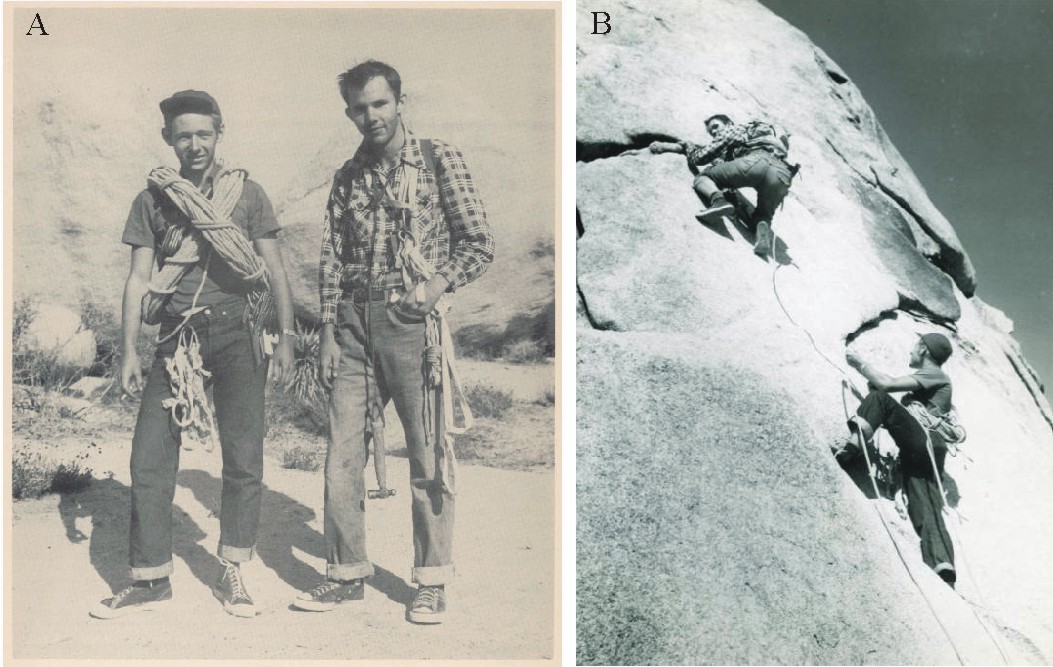

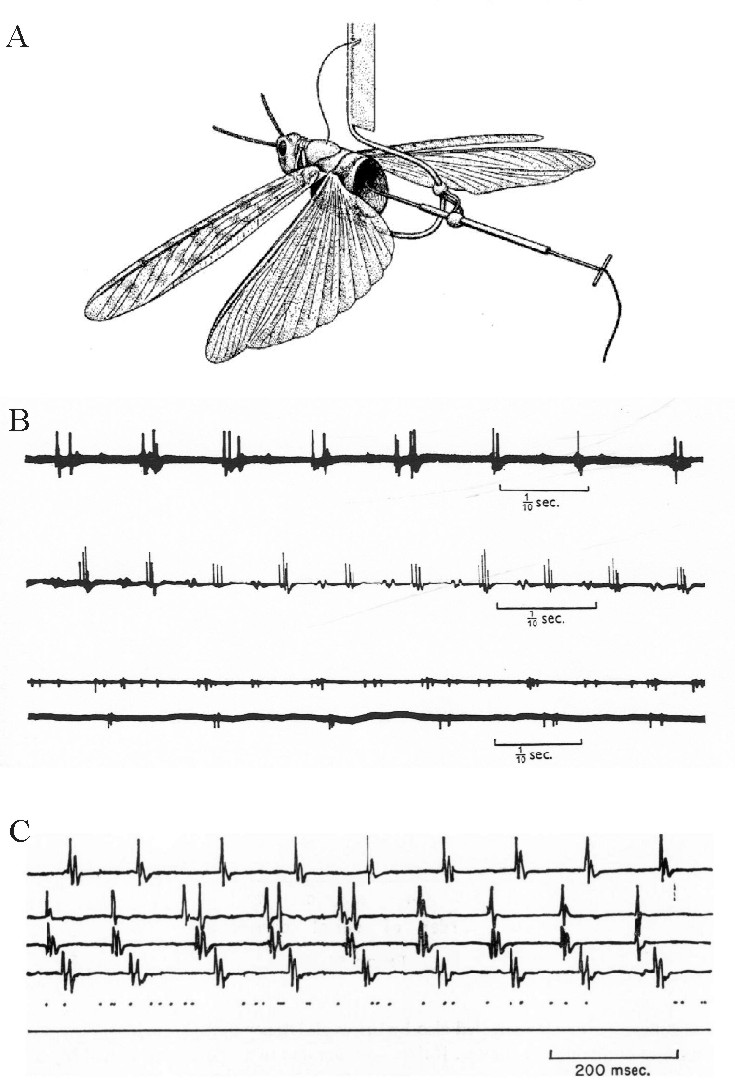

A:

Don Wilson (on left) and Frank Hoover, c.1952-53, when

Wilson

was an undergraduate at USC.

Check

out the climbing footwear.

From an article in

Summit

magazine, August 1956 (Photo by Niles

Werner.).

Original caption: “Off for

a Sunday practice

session of rock climbing are these members of the Angeles Chapter, Sierra Club

Climbing Section. Well-known

for their outstanding ability and agility on the rocks are Don Wilson and Frank

Hoover. Don recently made a “first ascent” of Spider Rock in Canyon de

Chelly National Monument, and Frank is presently Vice Chairman of the Angeles

Chapter Rock Climber.” B: Wilson

(lower right) belaying

Hoover

on Old Woman Rock in Hidden Valley Campground, Joshua Tree

National Park. (From

the Barbara Lilly Collection, Sierra Club Angeles Chapter Archives, photo by

Niles Werner.)

A

list of Wilson’s most significant

climbs (FA = First Ascent; FFA = First Free Ascent):

-

1952

FFA, Open Book (the first 5.9), Tahquitz, Idyllwild, CA

with Royal

Robbins.

-

1952

FA Super Pooper, Tahquitz, with Chuck Wilts, John & Ruth Mendenhall

-

1953

2nd ascent of Sentinel North Face, with Royal Robbins and Jerry Gallwas (2 days)

[See Camp

4, by Steve Roper, pg. 56, and Fail

Falling, by Royal Robbins]

-

6/1955

attempted Half Dome NW Face,

Yosemite

, with

Jerry Gallwas, Royal Robbins, and Warren Harding (reached 450' in 2.5 days).

[See Jerry Gallwas talk

about the attempt on YouTube and his write-up

of the 1955 attempt and the 1957 first ascent.]

-

3/1956

FA Spider Rock, with Mark Powell and Jerry Gallwas

-

6/1956

FA Lower Cathedral Rock East Buttress, with Mark Powell and Jerry Gallwas (14

hours)

-

9/1956 FA Cleopatra’s Needle, with Jerry Gallwas and Mark Powell

-

12/1956

FA Kat Pinnacle NW Corner, with Mark Powell

-

1957

FA, Finger Rock, north face (a.k.a. Bill Williams Memorial, Arizona), with

Mark Powell and Bill Feuerer

-

6/1957

FA Totem Pole (Monument

Valley), with

Mark Powell, Jerry Gallwas and Bill Feuerer

In

the third week of June 1955, Don Wilson, Royal Robbins, Jerry Gallwas and Warren

Harding attempted to climb the NW face of Half Dome in Yosemite, but a

series of problems ended the climb after two and a half days, by which time they

had ascended only about one quarter of the 2000-foot face.

In September 1955, the team was photographed and interviewed for an

article in the Saturday Evening Post (article titled “They risk their lives

for fun”, by Hal Burton,

Feb. 25,

1956

).

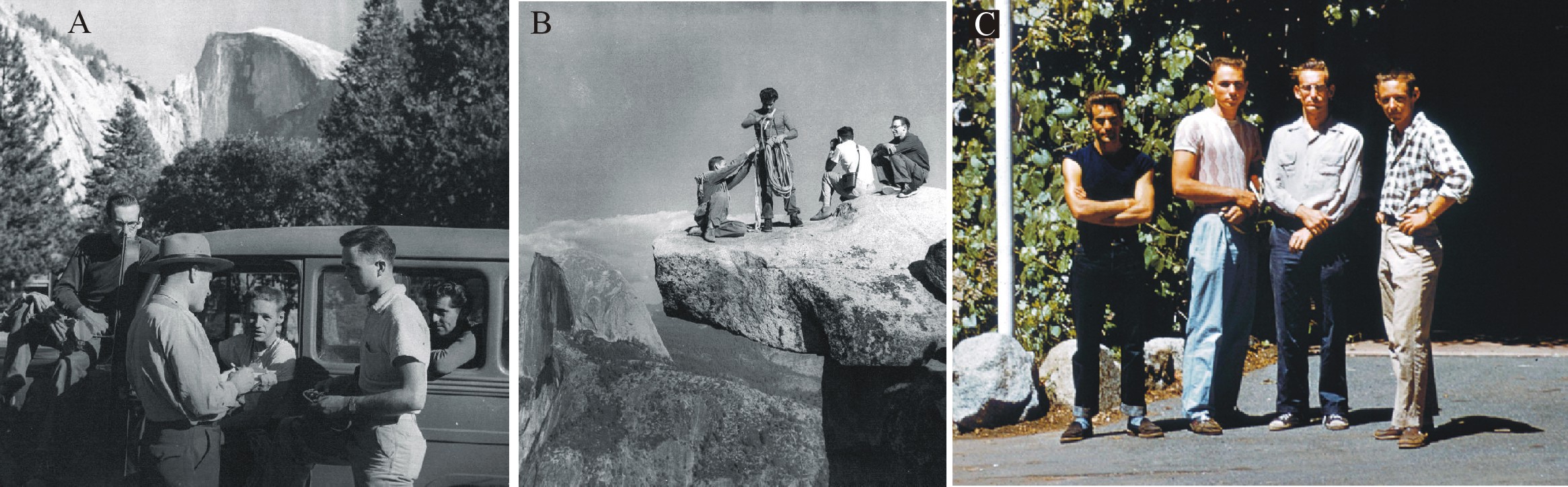

These photos were staged for the article, but were not used. A:

Left to right: Royal Robbins, unknown park ranger, Don Wilson (sitting in

driver’s seat), Jerry Gallwas and Warren Harding signing out at

Government

Center

in

Yosemite

National

Park

.

B: Posing on Overhanging

Rock at Glacier Point. Left to

right: Wilson, Harding, Gallwas, Robbins. Note Half Dome in background of both

scenes. (Photos courtesy of Jerry

Gallwas.) C: Left to right: Harding,

Gallwas, Robbins, Wilson. The contrasting body language of Wilson and

Harding has been explained by Jerry

Gallwas (see youtube

video, 3:49) and by Warren Harding (in his book, "Downward

Bound", pg. 107 ; Harding 1975). Robbins and Gallwas

returned to Half Dome with Mike Sherrick during the last week of June 1957 to

make the first complete ascent of the NW Face (Sherrick 1958; Gallwas, 2007).

Don Wilson was conducting research on squid at the MBL in Woods Hole, MA

during the successful 1957 ascent.

It's amazing, if nightmarish, to note that Alex

Honnold has since completed a ropeless free-solo climb (without

any harness or safety equipment) of Half

Dome's NW face in 2 hours, 50 min...

I

include here some brief excerpts from Don Wilson’s own published descriptions

of the three major

Desert

Tower

climbs –

Spider Rock, Cleopatra’s Needle and the Totem Pole.

I especially like his approach to the “legend of Spider Rock” as a

testable hypothesis. Both Spider Rock and

Totem Pole are fairly well-known landmarks. Spider Rock appeared in the

1969 Gregory Peck film "Mackenna's

Gold", although renamed "Shaking Rock" (see movie

clip). The fifth and

final officially permitted ascent of the Totem Pole was in 1975, when two

climbers were hired by Clint Eastwood and Universal Studios to locate a suitable

rock tower and “put the ropes up” for a climbing sequence in the film “The

Eiger Sanction” (Bjørnstad and Wyrick, 1976; Bartlett, 2010).

As part of a deal with the local Navajo council, the climbers removed all

existing hardware from the tower at the end of filming, including the can

(placed on the summit in 1957) containing the original summit-register of

Wilson, Powell, Gallwas and Feuerer. The register now resides in the collection

of the

Bradford

Washburn

American

Mountaineering

Museum,

Boulder,

Colorado

(Gallwas,

2010).

The

First Ascent of Spider Rock

[Don Wilson (1957) Sierra Club Bulletin 42(6): 45-49]:

“In Canyon de

Chelly

National

Monument

in northeastern

Arizona

is a great sandstone spire. According to the Navajos, who call it Spider Rock,

its summit is the home of the Spider Lady. Navajo

children are told that Speaking Rock across the valley informs the Spider Lady

of their misdeeds and that she will take them to her home and devour them. The

bleached rubble on the summit is supposed to be the bones of bad children.

Since the truth of this last statement is testable, it was possible to

disprove the legend of Spider Rock by examining the rubble at close range.

Of the three tried means of reaching a summit two were impossible here.

It was too small for an air-drop and too far away to throw a rope over.

It could be reached only by classical mountaineering methods in a

long-climb from the valley floor.”

[Spending

the night bivouacked on a ledge.] “…After

some canned sausages and gumdrops, we put all our clothing on, and tried to

sleep as much as possible, not so much for rest as for shortening the period of

consciousness of the cold. But as

large as our ledge was, it was not smooth and a comfortable position was not

possible. We were tied in, of

course, to prevent rolling off, and it was this fact that later became

dramatized in the newspapers to “they spent the night lashed to the cliff.”

We watched the sunrise and then waited for the sun to hit us before

breakfasting. It was only 200 more

feet now.”

[On

the summit.] “…During

the hour we spent on top we built

cairns

,

piling the “bones” into two

little monuments – not worried about our

disturbing an old legend. For some

time we enjoyed watching the spectators on the rim watching us.

Meanwhile Aubuchon [the

park Superintendant] drove to Chinle,

telegraphed our families, and informed the newspapers.

Spider Rock had been climbed.”

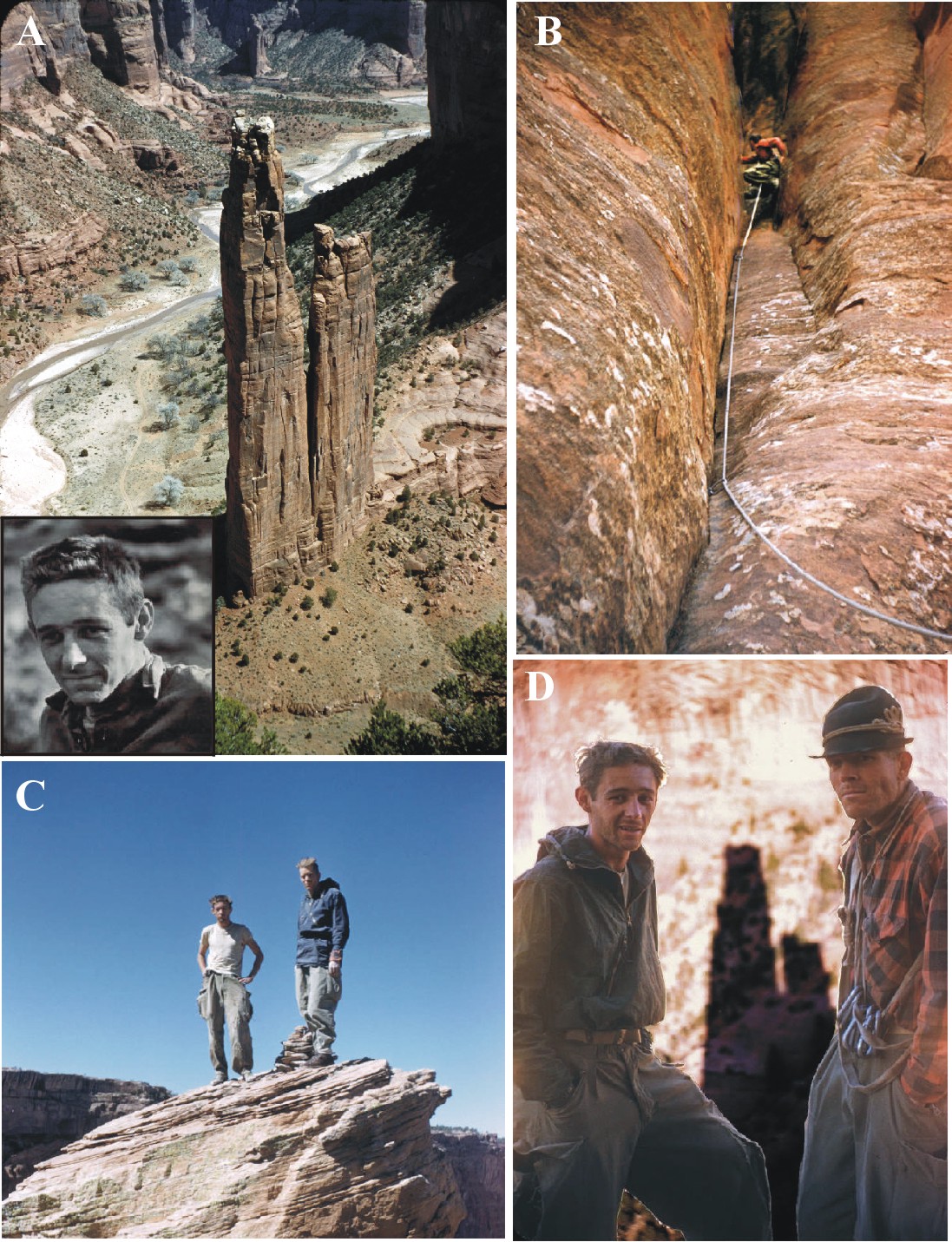

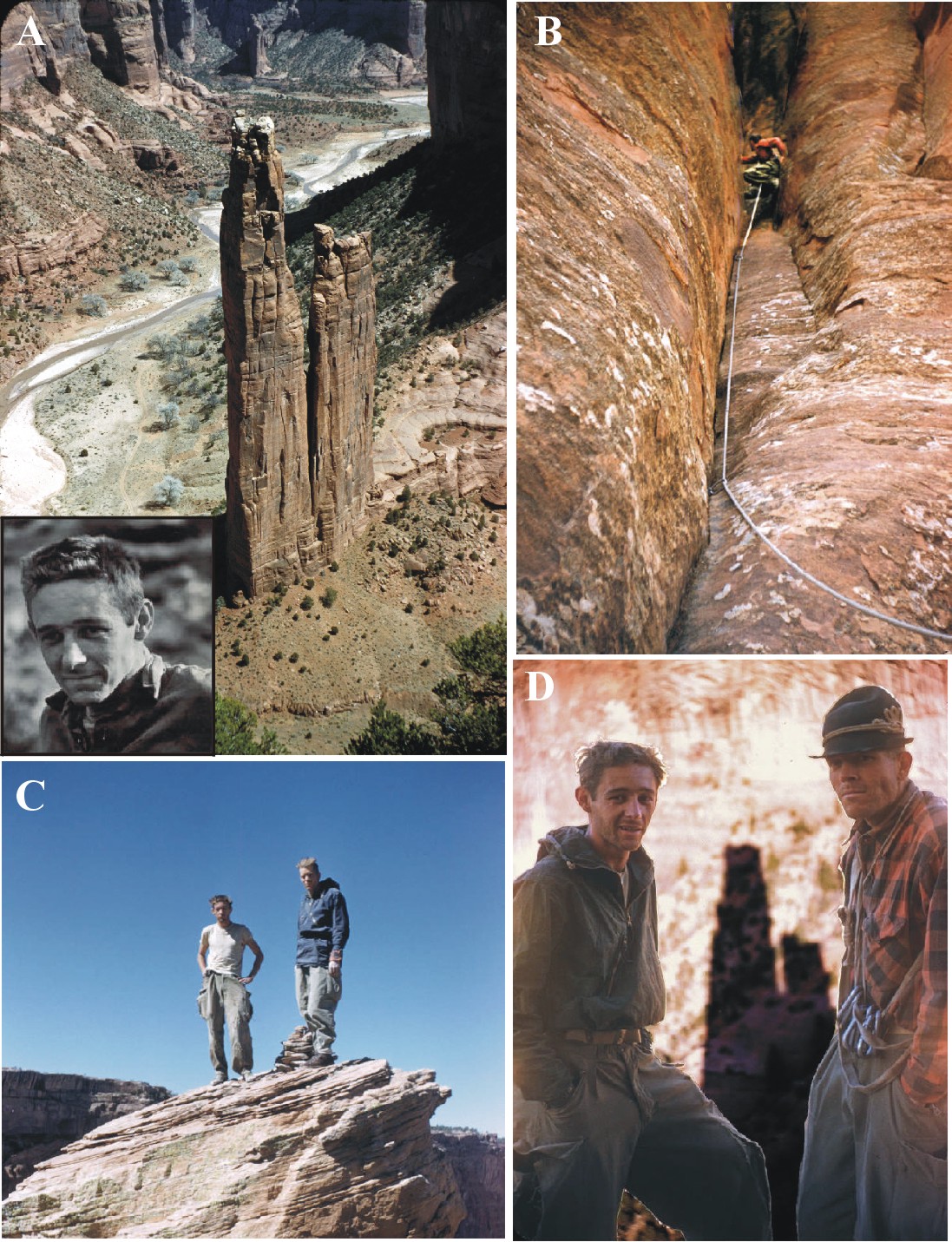

Spider

Rock, in Canyon de

Chelly,

AZ,

is the tallest free-standing spire in the world (832 feet from the bottomland to

the summit; approx. 2/3 the height of the

Empire

State

Building).

First

ascent made by Don Wilson, Mark Powell & Jerry Gallwas in March 1956. Wilson

was finishing his MS degree in biology at USC at the time.

A: Spider Rock, photographed

from the Overlook by Jerry Gallwas during a 1955 reconnaissance trip.

Inset: Donald

Wilson, c.1956-57 (Ascent Collection, courtesy of Steve Roper.)

B:

Wilson

ascending the “chimney” between the two spires.

C and D: Wilson and Powell on the summit (Wilson

on left. Note the shadow of Spider Rock in D).

(All photos except inset in A courtesy of Jerry Gallwas.

Gallwas, 2010)

Cleopatra’s

Needle

[Don

Wilson (1957) Sierra Club Bulletin 42(6): 63-64]: “For

several years we had known about a spectacular spire in

New

Mexico

through pictures advertising a bus company.

As we became familiar with sandstone climbing, we began to inquire where

that spire was, how high, how fractured and how soft the sandstone.

We found an article stating that the needle (they called it Spider Rock,

possibly confusing it with the one in Canyon de Chelly) was 265 feet high and

was in the

Valley

of

Thundering

Water

near

Fort

Defiance

,

Arizona

.

Mark Powell visited the valley last spring and brought back an excellent

report.”

[Describing

the soft rock and loose pitons.] “…I

unsnapped from my top piton and descended onto the next.

It began to pull out. Quickly

I lowered myself to the next. It

also shifted. The fourth held my

weight but now I could not reach back up to unsnap from the loose ones.

I came down to the ledge knowing that tomorrow’s leader had no pleasant

task.”

[On

the summit.] “...

Meanwhile on the summit, a ridge 10 feet long which we straddled, we became

aware of a new annoyance. All around

us thunder showers were brewing and we sat on a lightning rod over a plain.

But the clouds dissolved and we had the late afternoon sun as we built a

cairn and prepared our rappel anchor.”

Cleopatra's

Needle, in the Valley of Thundering Water, New Mexico. A: The spire

just after the arrival. First

ascent made by Don Wilson, Mark Powell & Jerry Gallwas in September 1956.

B: Another view, showing Wilson climbing up the base shortly after

arrival. Note Don and Nancy Wilson's VW Bug near the base of the spire in

both photos.

(Photos courtesy of Jerry Gallwas.

Gallwas, 2010)

The

Totem Pole

[Don Wilson (1958) Sierra Club Bulletin, vol. 43 (9): 72]:

“Several years of effort came to

an end last June when Bill Feuerer joined Jerry Gallwas, Mark Powell and me to

complete the first ascent of the Totem Pole in Monument Valley.

This effort began with an agreement between the three to try to climb

what they considered to be the three most important of the Southwest’s desert

spires: Spider Rock, Cleopatra’s Needle, and the Totem Pole.

At that time none of the desert’s great sandstone spires had been

attempted. Both of the first two

were climbed on the first try. Spider

Rock was highest, Cleopatra’s Needle the softest and therefore least safe, but

the last turned out to be the most difficult.”

[Making the summit, the day

after placing bolt screws in the rock.] “…The last morning we drove to the base

of the talus in Jerry’s jeep, and a caravan of spectators from the Post

followed after breakfast. On the

prussik lines we were harassed by gusts of wind which swung us 30 or 40 feet

across the rock face. We reached the

summit after about 13 hours of upward progress spread over the several days.

As we descended, a little rain fell, reminding us of the lightning which

had stopped the earlier party.”

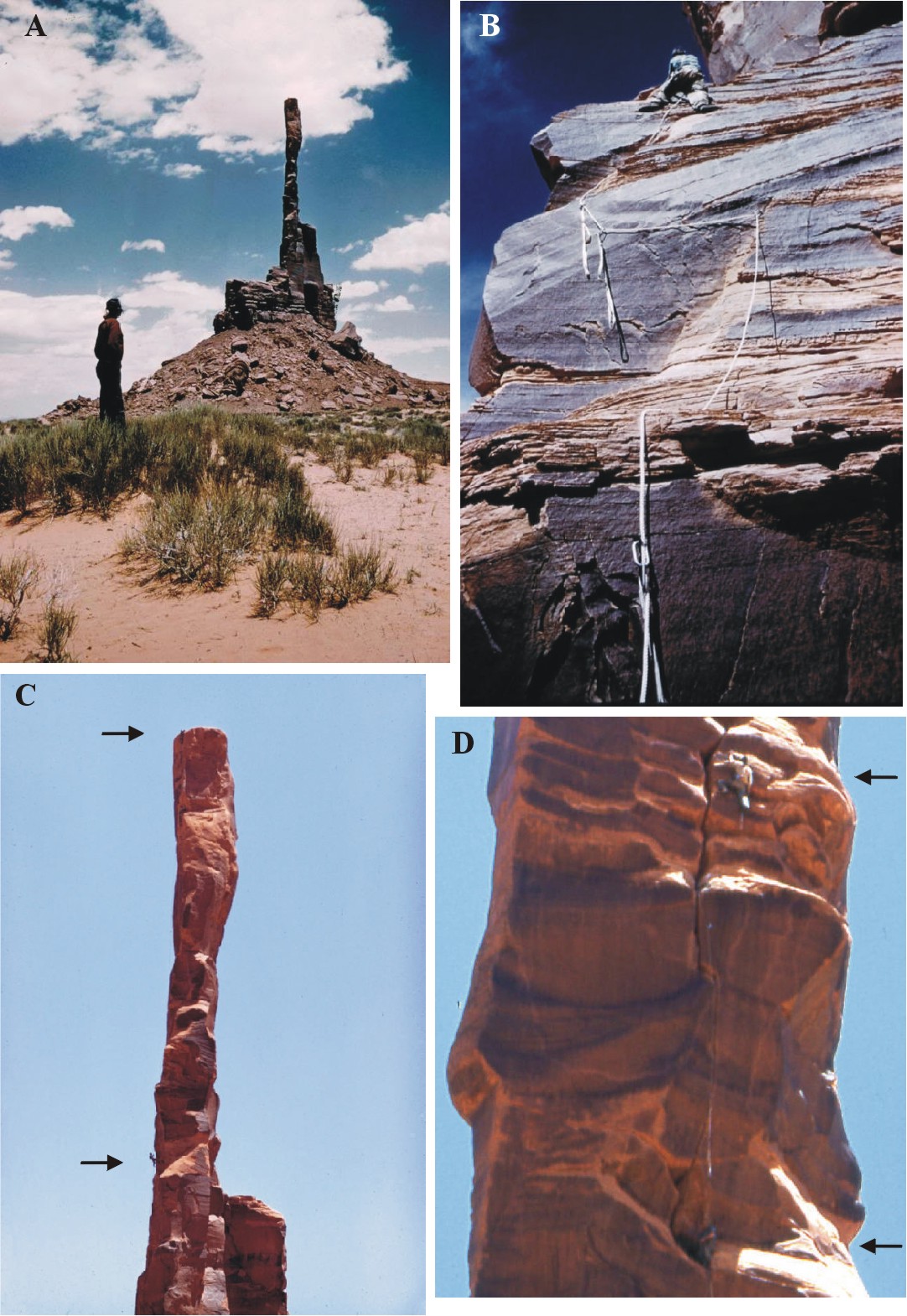

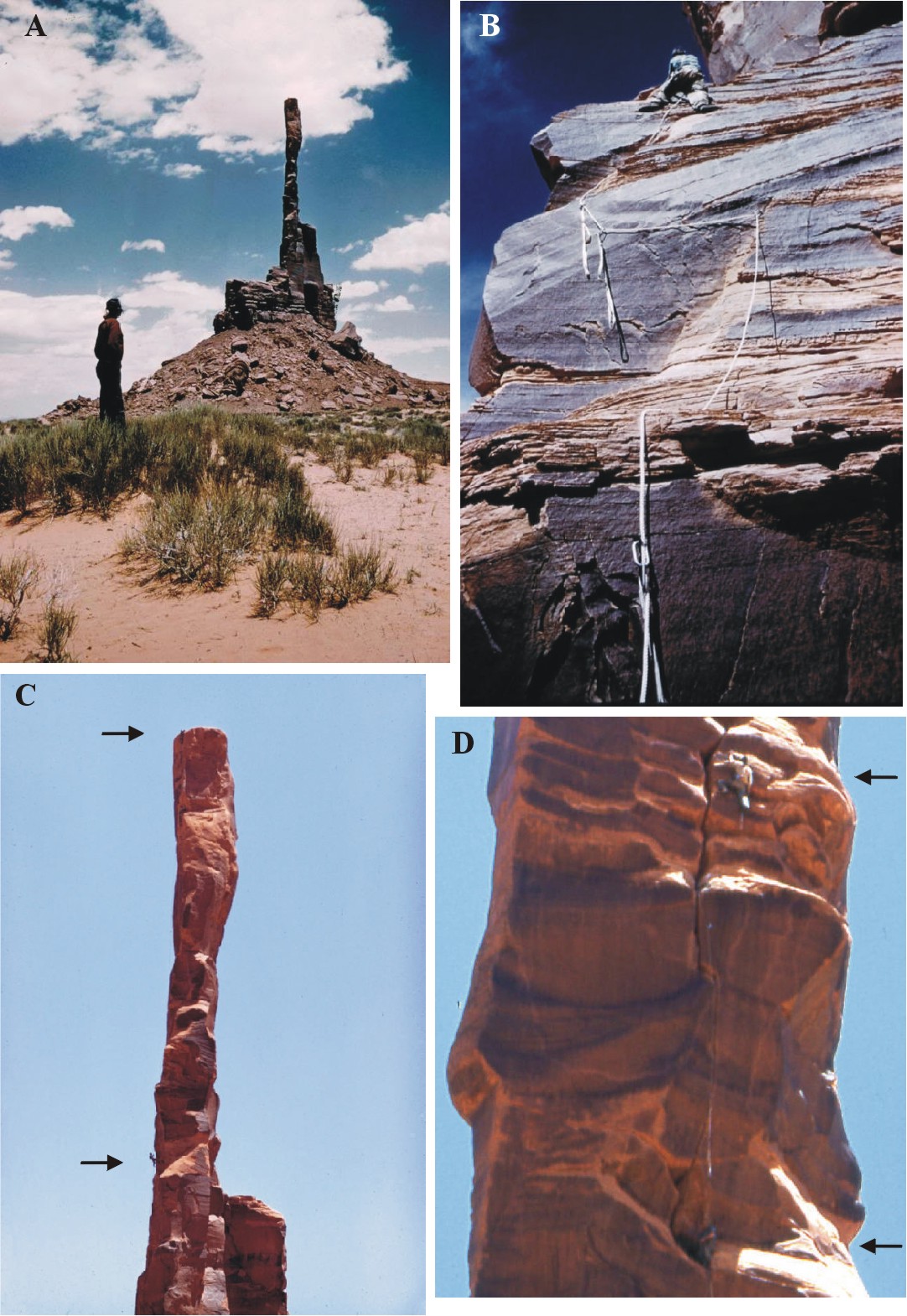

Totem Pole in

Monument

Valley,

Utah

(June 1957).

The first ascent team consisted of Don Wilson, Jerry Gallwas, Mark Powell and

Bill “Dolt” Feuerer. Wilson was

then a Ph.D. student in Theodore Bullock’s lab

at UCLA.

A: From a distance, with Navajo looking on.

B: Don Wilson leading a pitch

on the afternoon of the first day.

C: Gallwas climbing over the

lip of the summit (upper arrow) and

Wilson

“prusiking” (ascending a rope via a prusik line; lower arrow).

D: Powell leading (upper

arrow) with

Wilson

belaying (lower arrow). All photos

taken by Bill Feuerer (from the Dolt Collection, courtesy of Jerry Gallwas and

Don Lauria.)

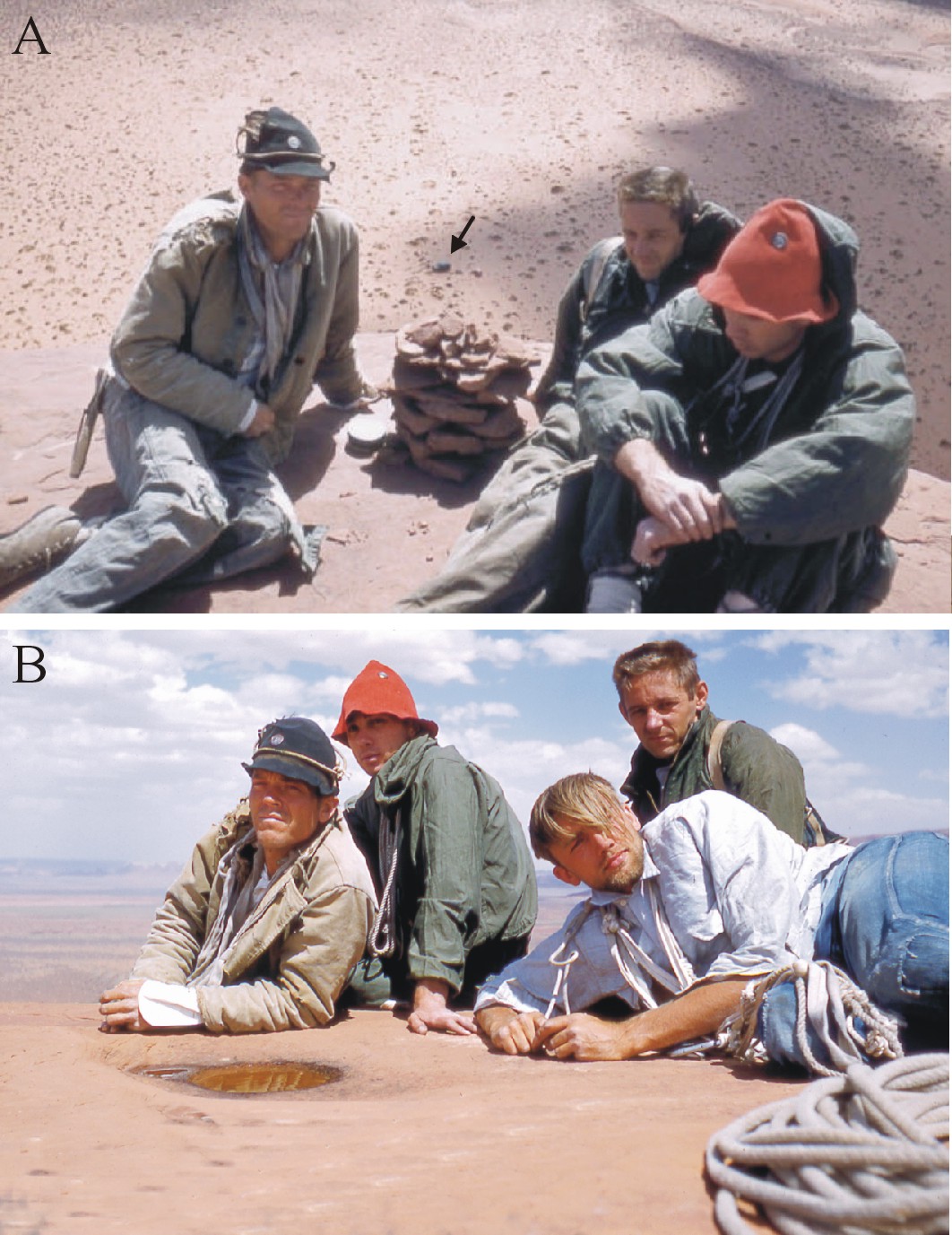

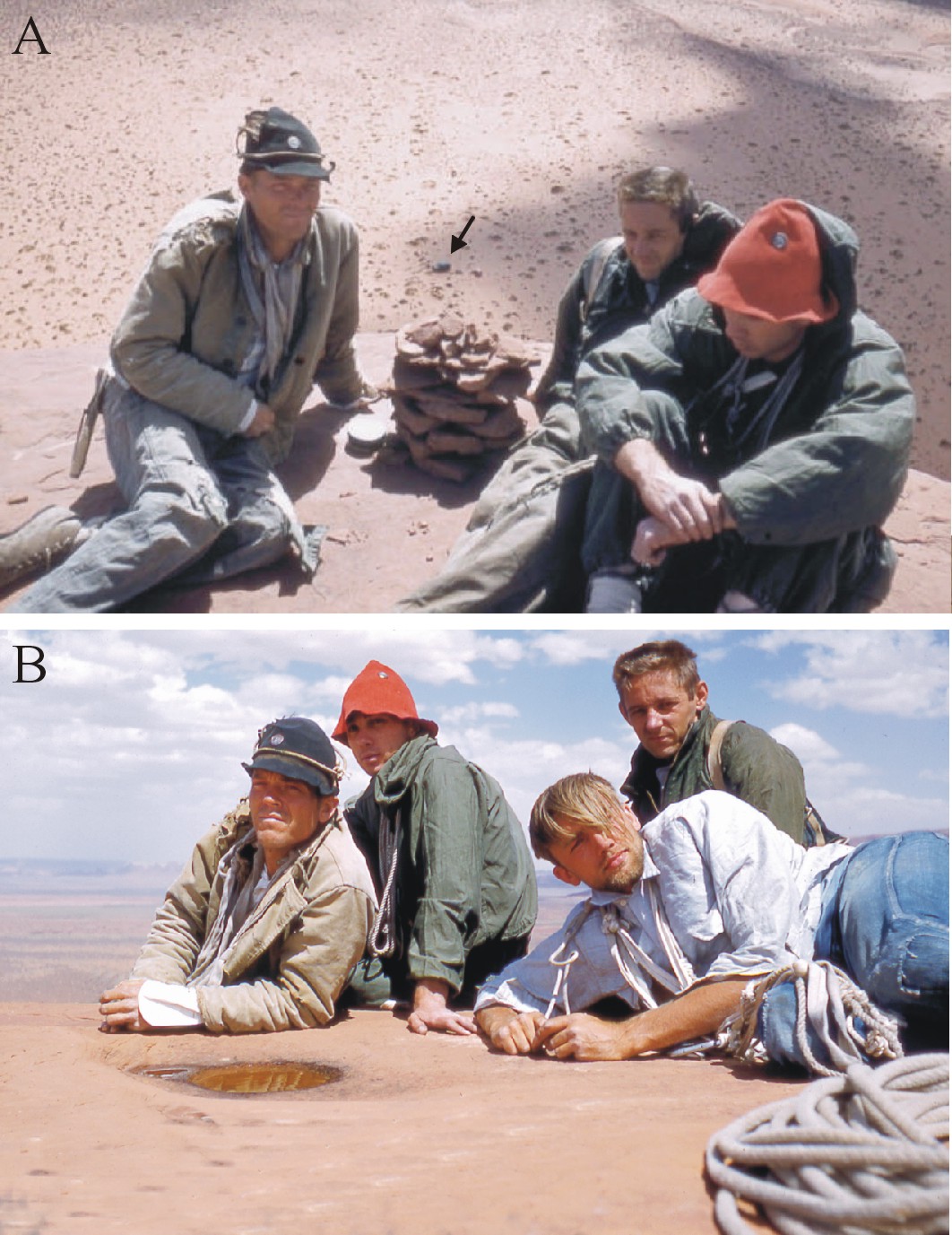

A:

On the 14 x 25-foot summit

of the Totem Pole, following the first ascent.

Photo taken by Bill Feuerer.

Left to right: Mark Powell, Don Wilson and Jerry Gallwas.

A tour bus is visible on the desert floor (arrow), just above the rock

cairn between Powell and Wilson. B:

Auto-timed shot of all 4 team members on the summit.

Left to right: Powell, Gallwas, Feuerer and Wilson.

Note the puddle in foreground. It had not been raining.

From Jerry Gallwas (pers. commun.): “The

picture of the four of us on top of the Totem Pole was taken with Bill Feuerer's

camera. There were 100 people on the

ground watching and we needed to pee so we gathered in a circle as if to pray

and used the only dimple on top.” (Dolt Collection, courtesy of Jerry Gallwas.)

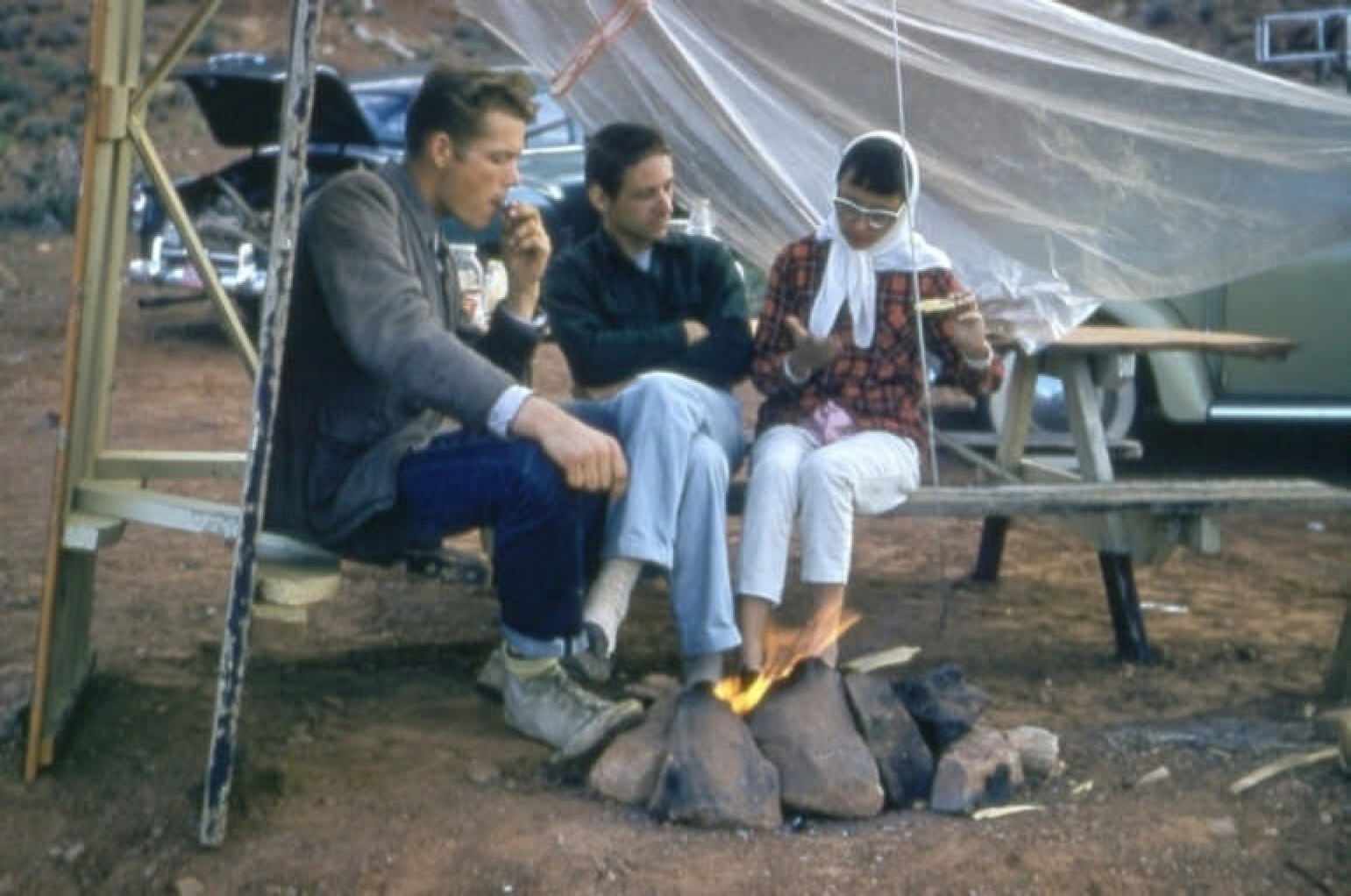

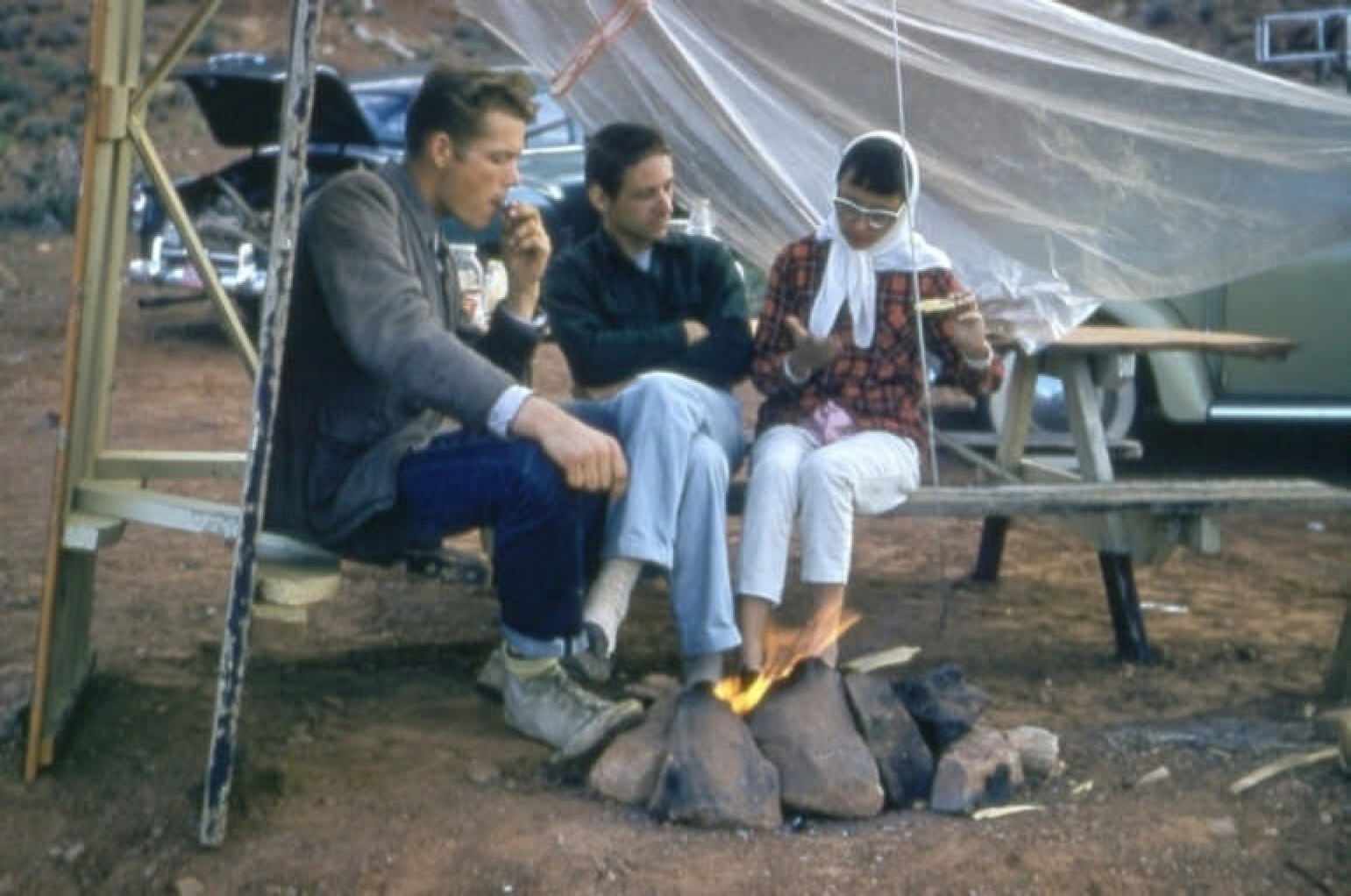

Warming

themselves at a campfire during a rainy day in Monument Valley.

Left to right: Mark Powell,

Don Wilson, Nancy Wilson. June 1957. (Dolt Collection. Courtesy of

Jerry Gallwas.)

Campus

Activism

While

at U.C. Berkeley (1961-68), Wilson

became

involved in the Free Speech Movement, the aim of which was

to give students the right to organize on campus in support of political causes.

He was close friends with its fiery student-leader, Mario

Savio, and a number

of graduate students and undergraduates in the Wilson

lab during

the mid-sixties were likewise active in the movement.

Wilson

named his

laboratory the “Sympathetic Ganglion” (written on a plaque above the door)

to indicate solidarity with the FSM (W.J. Davis, pers. comm.) and kept a

bullhorn in the lab “with which to address student rallies” (Edwards, 2006).

But political engagement on campus did not trump research progress.

Ingrid Waldron recalled that while Wilson was quietly supportive of her

campus political activities for about a year, he then insisted that it was time to get

to work and finish her thesis – prodding her to “finish in a

respectable five years, instead of six”

(I. Waldron, pers. comm.).

In July 1968, Wilson

left U.C.

Berkeley for Stanford, following a disagreement with his Department Chairman

regarding the use of grades to alter military draft status (Mulloney and

Smarandache, 2010, footnote 2). But,

his activism continued at Stanford, where W. Jackson Davis (who was then a

post-doctoral fellow in Don Kennedy’s Stanford lab) remembered being “first

tear-gassed by a helicopter with Don (Wilson)… near

the tower.” (W.J. Davis, pers. comm.).

Rafting

and the fatal accident

In 1959, Wilson and life-long friend Frank Hoover went

rafting together for the first time at Glen Canyon on the Colorado river (Frank

Hoover, pers. commun.). They took to this new adrenaline rush as they had

to rock climbing as teenagers, and by 1970, Wilson, Hoover and their circle of

friends had navigated a long list of the most

challenging white water in the western U.S., including the Rogue river in Oregon (during flood

stage), and the Cataract and Grand Canyon legs of the Colorado (Frank Hoover

and Ken Boche, pers. commun.; Al

Bukowsky's interview with Middle Fork river-guide, Roy

Nicholson, 2012; Couture,

1971). According to most accounts, Wilson's accidental death at the age of 37 occurred on Sunday June 21, 1970 (Couture,

1971; Collins and Nash,

1978), while rafting the Middle Fork of the

Salmon

River

in north

central Idaho.

However, it was reported as June 23 in his obituaries (Hoover,

1970; Kennedy et al.,

1970). The river was extremely flooded and especially turbulent that week from recent

snow melts, running at speeds up to 15-20 miles per hour with waves as high as

10-20 feet (Couture, 1971;

Collins and Nash, 1978; Al

Bukowsky, pers. commun.). Wilson

led a

party of nineteen people that included Frank Hoover in four of Hoover’s

WWII-era 10-man

rafts (Hoover, pers. commun.; Collins and Nash, 1978).

Wilson

was at the

oars of his raft, which had a broken oar-lock. Only 15-20 minutes

after

launching near Dagger Falls, they were entering Velvet Falls about 4 miles

down-river (below the mouth of

Sulphur

Creek, where it meets the Middle Fork; see map

1, map

2), when a member of Wilson's party was ejected from the back of the raft and carried by the water into some

brush at the river bank (from Al

Bukowsky's interview with Roy

Nicholson, 2012; see also recent rafting

and kayaking videos of

Velvet Falls.) Seeing this, Wilson

ran his

raft aground on "an island" or shallow embankment near the opposite

shore (Hoover,

1970;

Frank Hoover, pers. commun.) and

attempted to swim across the river to rescue the crew member with his raft's

bow-line tied

around his waist, secured on its other end to the raft.

This was a lethal mistake that might have resulted from Wilson's rock-climbing

habits and the panic of the moment. When he entered the river, the powerful current immediately swept him off

his feet and pulled him down-stream and under water, taut at the end of the rope.

By the time he was pulled back in, he had already drowned. The

ejected crew member had made it to shore and was unharmed.

Amongst the devastated

survivors, some decided to hike back to the

Dagger

launch site, while

others continued down river with Wilson’s body

for another 26 miles to over-night near the Indian Creek

Airstrip.

A light aircraft arrived the next day to pick the group up, and Wilson’s ashes

were later spread on the Middle Fork (Frank Hoover, pers. commun.; Hoover, 1970;

Collins and Nash, 1978; Robbins, 2009). He

was survived by his ex-wife, Nancy, and four children.

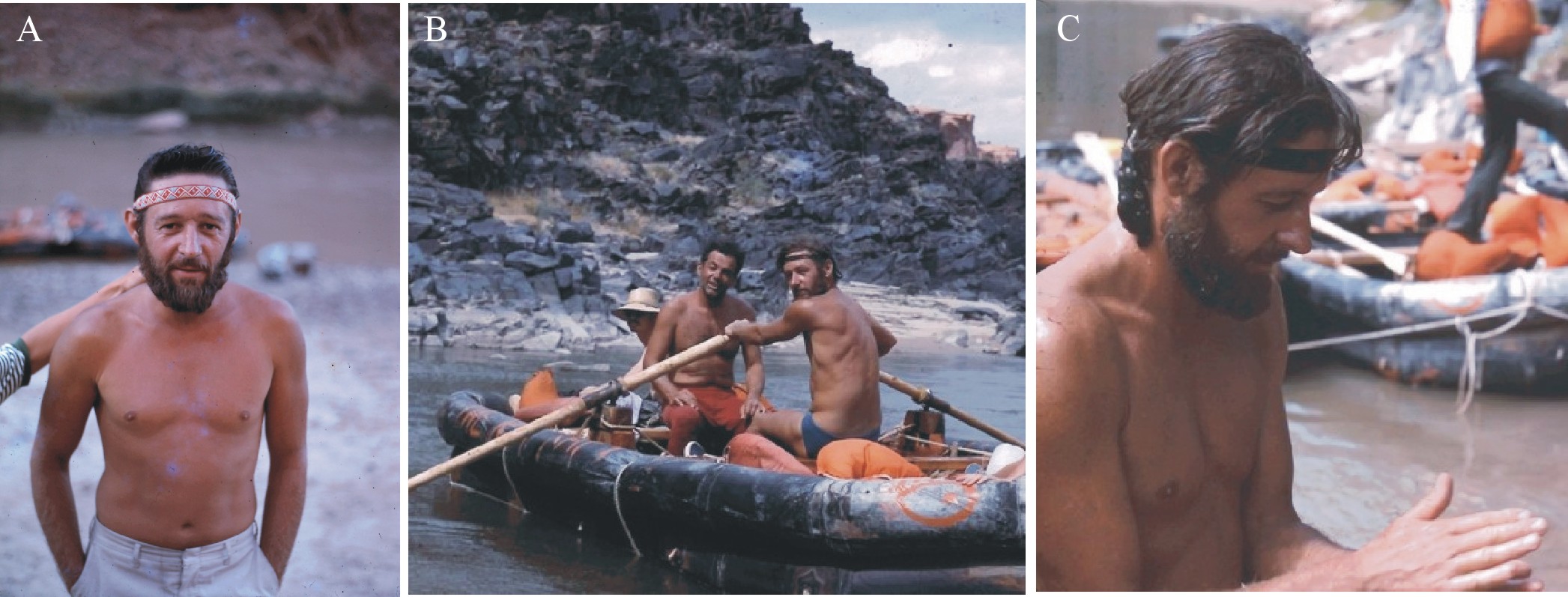

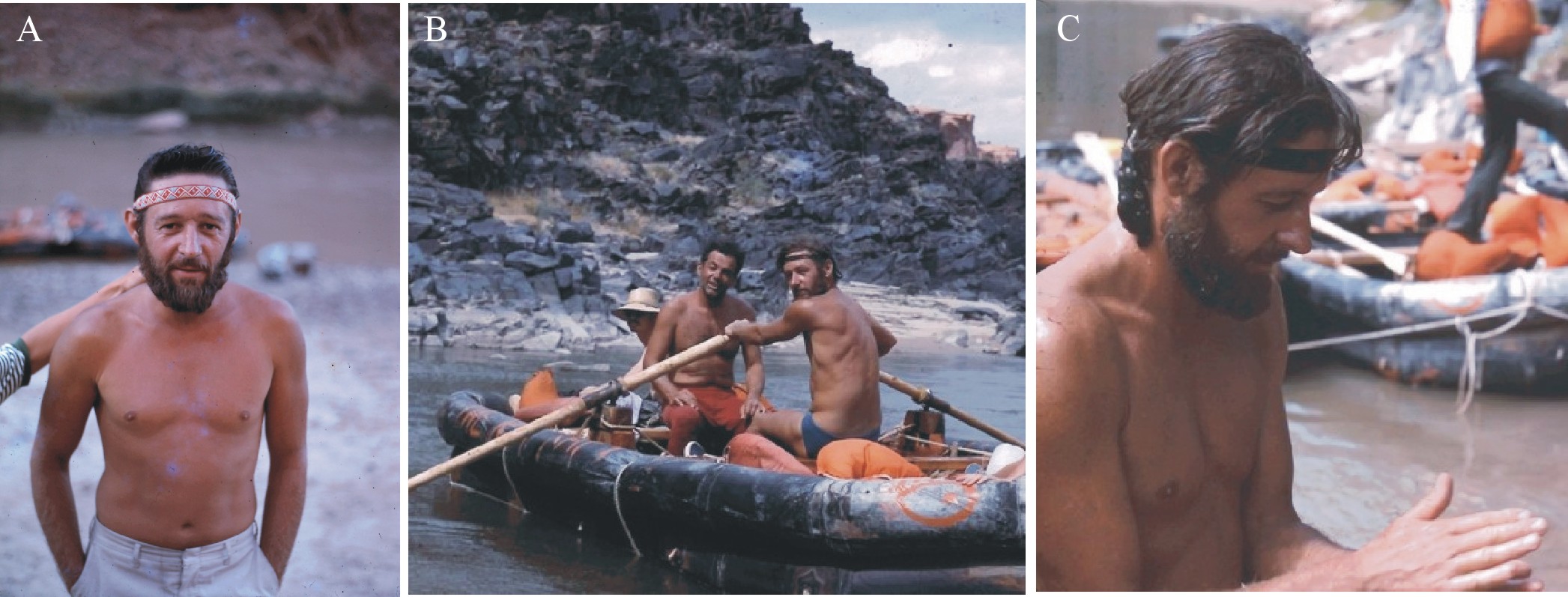

Donald Wilson in 1969, during a rafting trip on the

Colorado

river

.

A:

Cataract

Canyon,

Glen

Canyon

National Recreational Area, Utah.

B:

Wilson

holding the oars,

Westwater

Canyon,

Colorado.

C: With a captured spadefoot toad.

(Photos courtesy of Ken

Boche).

Wilson’s

fatal rafting trip on the Middle Fork of the

Salmon

River

in Idaho

occurred about one year later at “Velvet

Falls”

(see map),

so named because the rapids make little or no sound until you are upon them

(Collins and Nash, 1978).

That same Sunday

afternoon of June 21, two other groups launched from Dagger Falls ahead of the

Wilson party. Tom Brokaw (the future NBC News anchor) was with a group led by river-guide Everett Spaulding (Brokaw, 1970; Collins and Nash, 1978).

The other party was led by Al Couture (Couture,

1971). Both groups struggled, but made it safely through Velvet Falls

and continued down-river until Thursday June 25.

Neither party learned of Wilson's accident until later. On Thursday, Brokaw’s close friend Ellis Harmon and Spaulding's associate Gene

Teague were both swept away and

killed at Weber

Rapid (downstream from the site of Wilson’s

accident, referred to by Brokaw as “Webber

Falls”) when

their McKenzie boat was swamped and sank in the white-water. Brokaw

wrote about it a few months later in an article titled “That river swallows

people. Some it gives up. Some it don’t.” (Brokaw, 1970; the title coming

from a Spaulding quote). In the following

excerpt from Brokaw's article, he mentioned the fate of a “Stanford

professor” (Wilson):

“That week the Middle Fork and

the main Salmon swallowed six people. On

the main Salmon two

U.S.

Forest

Service employees drowned when their pickup truck was forced off the road into

the river, and a

Detroit

teenager was swept away when his kayak capsized.

A Stanford professor drowned in the Middle Fork when he attempted to

cross the river while attached to a rope. At

the time we were unaware of the deaths. When

word of our accident spread, two parties behind us which included Sir Edmund

Hillary, the conqueror of Mt. Everest, and Frank Gifford, the sportscaster and

former football star, got out of the river at the Flying B Ranch.”

The Couture party was the only one of the three groups that launched on

Sunday to make it through the trip without a fatality. In the Outdoor Life

article that Al Couture published several months later (Couture,

1971), he described seeing one of the bodies from the Spaulding group float by in a life preserver

near the Cradle Creek campground while he and his party were pulling their boats

in to a quiet backwater. Gene Teague was

never found.

The Middle Fork has more than forty sets of rapids, but when flooded by

spring snow-melts, it becomes essentially one continuous rapid along its whole

length, from Dagger

Falls

to the

confluence with the greater Salmon

River.

A few summers later (June 1974), the U.S. Forest Service warned that any

attempt to run the flooded Middle Fork was “suicidal” (Collins and Nash,

1978). The third week of June 1970

was the deadliest in the river’s modern history, and remains infamous amongst

Middle Fork rafting guides (Al Bukowsky,

pers. commun.).

References

Neuroethology

Bullock,

T.H. (1995)

Neural integration at the mesoscopic level: the advent of some ideas in

the last half century. J. Hist. Neurosci. 4 (3-4): 216-235.

Burrows,

M. (1975) Monosynaptic connexions between wing stretch receptors and

flight motoneurones of the locust. J. Exp. Biol. 62: 189-219.

Currie, S.N.

(2010) The short intense life

of Don Wilson: Neuroethology pioneer, elite rock climber, activist and

adventurer. Soc. Neur. Abstr. vol. 36.

(See http://faculty.ucr.edu/~currie/wilson.pdf)

Currie,

S.N. (2011) Donald M. Wilson (1932-1970): "The point that must

be reached." Neuroethology Newsletter (March issue). https://www.neuroethology.org/Portals/2/Mar_11.pdf

Edwards,

J.S. (2006) The central nervous control of insect

flight. J.

Exp. Biol. 209: 4411-4413.

Hoyle,

G. (1980)

Neural mechanisms. In: Insect

Biology in the Future. Academic

Press, N.Y., pp. 635-665.

Kennedy,

D., Davidson, J.M. and Hanawalt, P.C. (1970)

Memorial resolution: Donald M. Wilson (1933 –

1970). Stanford

Historical Society, Faculty Memorials. http://histsoc.stanford.edu.

Mulloney,

B. and Smarandache, C. (2010) Fifty years of

CPGs: two neuroethological papers

that shaped the course of neuroscience.

Front. Behav. Neurosci. 4:45.doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2010.00045.

Nachtigall,

W. and

Wilson

, D.M. (1967)

Neuro-muscular control of Dipteran flight. J.

Exp. Biol. 47: 77-97.

Robertson,

R.M. and Pearson, K.G. (1985)

Neural circuits in the flight system of the locust. J. Neurophysiol. 53: 110-128.

Sherrington,

C.S. (1947)

The Integrative Action of the Nervous System.

Yale

Univ.

Press,

New Haven

,

CT.

Stuart,

D.G. (2007)

Reflections on integrative and comparative movement neuroscience. Integrative

and Comparative Biology 47 (4): 482-504.

Wilson,

D.M. (1959)

Function of giant Mauthner’s neurons in the lungfish.

Science 129: 841-842.

Wilson,

D.M. (1960a) Nervous control of movement in annelids. J.

Exp. Biol.

37: 46-56.

Wilson,

D.M. (1960b) Nervous control of movement in cephalopods. J.

Exp. Biol.

37: 57-72.

Wilson,

D.M. (1961a) The central nervous control of flight in a locust. J.

Exp. Biol. 38: 471-490.

Wilson,

D.M. (1961b) The connections between the lateral giant fibers of earthworms. Comp.

Biochem. Physiol.

3: 274-284.

Wilson,

D.M. (1965) Proprioceptive leg reflexes in cockroaches. J. Exp. Biol. 43:

397-409.

Wilson,

D.M. (1966)

Central nervous mechanisms for the generation of rhythmic behaviour in

arthropods. SEB Symposia 20: 199-228.

Wilson,

D.M. (1967)

Stepping patterns in tarantula spiders.

J. Exp. Biol. 47: 133-151.

Wilson,

D.M. (1968a)

Inherent asymmetry and reflex modulation of the locust flight motor

pattern. J. Exp. Biol. 48:631-641.

Wilson,

D.M. (1968b)

The flight-control system of the locust.

Scientific Amer. 218 (5): 83-90.

Wilson,

D.M. and Gettrup, E. (1963)

A stretch reflex controlling wingbeat frequency in grasshoppers. J.

Exp.

Biol. 40: 171-185.

Wilson,

D.M. and Waldron,

I.

(1968) Models for the generation of

the motor output pattern in flying locusts. Proc.

IEEE 56 (6): 1058-1064.

Wilson,

D.M. and Weis-Fogh, T. (1962) Patterned activity of co-ordinated motor units,

studied in flying locusts. J. Exp. Biol. 39: 643-667.

Wilson,

D.M. and Wyman, R.J. (1965) Motor

output patterns during random and rhythmic stimulation of locust thoracic

ganglia. Biophys.

J. 5: 121-143.

Climbing and Rafting

Bartlett, S. (2010)

Desert

Towers

: Fat Cat Summits and Kitty Litter Rock. Sharp End Publishing LLC, Boulder,

CO. (See pp.37-75.)

Bjørnstad,

E. and Wyrick (1976)

The Totem Pole and the Eiger Sanction. Summit

12 (No.3; June 1976).

Breed,

J. (1958)

Better

days for the Navajos. The National Geographic Magazine, vol. CXIV, No.6

(December). (Discussion and photos of Totem Pole 1st ascent on pp.

830-831.)

Brokaw,

T. (1970)

“That river swallows people. Some it gives up. Some it don’t.” West

(Nov. 1) 11-18. Re-printed in: River

Reflections: A Collection of River Writings, edited by Verne Huser. 3rd

edition,

Univ.

of

New Mexico Press,

Albuquerque.

Burton, H. (1956)

They risk their lives for

fun. Sat.

Evening Post 228 (Issue 35, Feb. 25): 34-102.

Collins,

R.O. and Nash, R. (1978)

The

Big Drops: Ten Legendary Rapids.

Ch.

6: Redside. Sierra Club Books, San Fransisco, pp. 117-118.

Couture,

A.E. (1971) Death ran

with the river. Outdoor Life (May Issue).

Gallwas,

G. (2007) Half

Dome: First ascent of the North West

Face. (Prepared for the 50th

Anniversary Reunion of the First Ascent, 1957.) Unpublished PDF, 83 pp.

Gallwas,

G. (2010) The

Desert Spires: Spider Rock,

Cleopatra’s Needle, & the Totem Pole. (Introduction and personal

recollections with original articles, pictures, and selected reading materials.

Unpublished PDF, 52 pp.

Harding,

W. (1975) Downward

Bound: A Mad! Guide To Rock Climbing. Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs,

NJ., pgs. 107 and 197.

Hoover,

F. (1970)

Donald M. Wilson – Obituary. Mugelnoos

– rock climbing newsletter (July 15) p.4.

Jones,

C. (1976) “The

Southern Californians

” From: Climbing

in

North America

.

University

of

California

Press,

Los Angeles

, 1976. pgs. 197-212.

Robbins,

R. (2009) To

Be Brave. Pink Moment Press, Ojai, CA., p. 208.

Robbins,

R. (2010) Fail

Falling. Pink Moment Press, Ojai, CA.

Roper,

S. (1970) Four corners. Ascent

1(Number 4, May): 26-36.

Roper,

S. (1994) Camp

4: Recollections of a Yosemite Rock Climber. The Mountaineers (publ.),

Seattle, WA.

Sherrick,

M.P. (1958) The northwest face of Half Dome. Sierra

Club Bulletin 43 (9): 19-23.

Supertopo.com

Climber’s Forum: http://www.supertopo.com/climbing/thread.php?topic_id=1084204&msg=1084750

Wilson

, D.M. (1957a) The first ascent of spider rock. Sierra

Club Bulletin 42 (6): 45-49.

Wilson,

D.M. (1957b) Cleopatra’s Needle. Sierra

Club Bulletin 42 (6): 63-64.

Wilson

, D.M. (1958) The Totem Pole. Sierra Club

Bulletin 43 (9): 72.

Wilts,

C. and Wilson, D.M. (1956) Climber’s

Guide to Tahquitz Rock. American Alpine Club,

New York, NY, 36 pp.

Acknowledgements

Grateful

thanks to many gracious people in and around academia who shared their

recollections of Don Wilson, including his widow, Nancy Wilson, Robert Wyman

(Yale Univ.), W. Jackson Davis (UC Santa Cruz, Emeritus), John S. Edwards (Univ.

Washington) and Ingrid Waldron (Univ. of Penn.).

Special thanks to Frank Hoover (Wilson’s life-long friend and climbing /

rafting partner), who very generously permitted me to interview him over the

phone on several occasions while he recuperated from an auto accident.

Thanks also to Jerry Gallwas (Conqueror of Half-Dome!; made many important climbs with Wilson in the

1950s) Steve Roper, Ken Boche (rafted with Wilson and Hoover in 1969), Fred Martin

(long-time friend and rock-climbing partner of Wilson and Hoover) and Don Lauria

of the

rock-climbing Diaspora, for permission to use their photographs and

remembrances. Finally, thanks to Middle Fork river-guide, Al Bukowsky (Solitude

River Trips) for answering my many questions, giving me an authentic, dog-chewed

copy of Outdoor Life magazine from 1971 containing Al Couture's article, and

providing me with a copy of his 2012 interview with fellow Middle Fork river-guide, Roy

Nicholson.