Fichero: <Decalogue

Stone. htm> <Página

principal> <Índice> <Arqueología>

|

THE LOS LUNAS, NEW MEXICO DECALOGUE STONE (Contact) Following is a discussion of "The

Los Lunas Decalogue Stone: Genuine or Hoax?" by Mark

Perkins and Titus Kennedy

Please CLICK on Subjects and Numbered links for further

information: (Also see discussion of Mexico artifacts by

Franz

Tamayo)

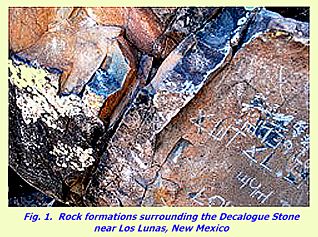

In Dixie Perkins’s essay, “New Mexico’s

Mystery Stone,” she describes a stone inscribed in Ancient Near

Eastern languages, found in the desert west of Los Lunas, New Mexico 1. Intrigued by this Mark Perkins and Titus

Kennedy set out to locate what has become to be known as the Decalogue

Stone. It should be mentioned

at this juncture that a hieroglyphic inscription on leather in Mexico known

to Alexander Humboldt and subsequently analyzed by Franz

Tamayo bears the same message of The

Ten Commandments as the Decalogue Stone. However, the authors of The Los Lunas Decalogue Stone:

Genuine or Hoax?" either

were unaware of its existence or decided not to mention it. Their efforts to declare it as unauthentic

have taken precedence. The existence of

Pre-Columbian accounts of The Ten

Commandments in America is of course historically of the utmost

importance. Following the advice of local residents they

proceeded through ancient Native American sites and reached a place that

would have been no more than a temporary campsite en route to another

destination. 2 .

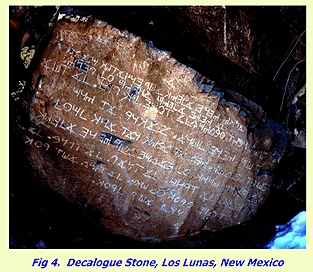

There they found a large boulder with its lower

portion chiseled flat and bearing nine lines of inscriptions. As they drew closer to the stone and

analyzed the inscription, it was apparent that the forms of the letters were

inconsistent. Some letters followed

Phoenician forms dating as far back as the 11th century B. C. E., while

other letters followed Samaritan forms as late as the 7th century A. D. , and

still others matched forms from ancient Greek script. As they further analyzed the surface of

the stone and the inscription itself, coupled with the history surrounding

it, their skepticism increased. The site turned out to be about

ten miles from the Rio Grande,

a navigable river in ancient times, and about a mile from a reliable source

of water, the Rio Puerco. A boundary mark that is not at a

prominent landmark or does not function as a prominent landmark itself is not

a good boundary mark. This location

would not serve as a good place for a rendezvous, either. No matter the century, the little arroyo

would be difficult to describe and more difficult to find. Fig. 3. CLICK to enlarge After an analysis of the stone and

several photographs, the two explorers began their return to Albuquerque

because it seemed there was little doubt that the stone was a hoax. Nevertheless, they wondered who might have

made the inscriptions. Was it the two

centuries old hoax of a Spanish Priest?

A converso Crypto-Jew who settled in the area during the colonial

period? While the settlement of

converts from Judaism to Catholicism who fled Spain to various countries

could have taken place in New Mexico as early as the 17th century, there was also

a migration of Ashkenazi Jews to New Mexico in the late 19th century. 3. The main problem with the Spanish Priest

and Crypto-Jew theories is that the majority of the letter forms used in the

inscription were not rediscovered until the late 19th century and early 20th century, which narrows

the time frame. Was it made by a

Mormon traveler to prove the archaeological veracity of the Book of Mormon? While possible, it is doubtful as the

inscription is not highly promoted by Mormon scholars, and one prominent

Mormon Brigham Young University

professor bluntly stated that it was faked. 4. Could it perhaps have been an early 20th century University of

New Mexico professor seeking credibility, or even an odd rancher from the

period who had some knowledge of ancient Hebrew and a keen interest in

ancient epigraphy? Only further

investigation could determine this. The stone was first recorded in

1936 by archaeologist Frank C. Hibben

of the University of New Mexico. 5. Hibben held a PhD in anthropology and was

a specialist in archaeology of the Southwest United States, focusing on

Native American cultures.

Unfortunately, Hibben was suspected of multiple fraudulent

archaeological activities during his career.

First, there was the Sandia Man

incident in which he was suspected of planting objects in the Sandia Cave to

support his thesis that there were people living in the area 25,000 years

ago. The thesis was not accepted,

although the evidence for his fraud on this matter is inconclusive. 6. The second incident occurred in Alaska

where Hibben claimed to have found a specific type of arrowhead matching

those of the Folsom culture in the High Plains region 10,000 years ago. This theory had no further support and

simply added to suspicions that Hibben sometimes made fraudulent

archaeological claims. 7. The third incident was the alleged

discovery of the Decalogue Stone. Hibben was the first to mention the stone,

and claimed that he was led there by a conveniently unnamed guide who found

it sometime in the 1880s. There is no

verifiable evidence to support Hibben’s claim, which is questionable based on

those three incidents and the accusations of forgery surrounding them. Other than a small, almost unknown

journal called Epigraphic Society Occasional Publications, only two well-known

scholars have published anything about the inscription. 8 . James Tabor of the University of North Carolina-Charlotte and Cyrus

Gordon of Brandeis University interacted

with the inscription. Tabor, a

conspiracy theorist who was behind archaeological and historical fantasies

such as the “Jesus Tomb” ossuaries

and the “Jonah” ossuary, both

which have been overwhelming rejected by scholars, interviewed Hibben about

the Decalogue Stone. He visited the site, and claimed that the

inscription was made by Israelites sometime in the B. C. E. era. 9 . He offered no detailed analysis of the

inscription and no plausible reason as to its antiquity other than the letter

forms. Cyrus Gordon theorized that

the Decalogue Stone was a Samaritan

mezuzah as part of an overall thesis that during Byzantine times, Samaritans

and others from the Near East dispersed all over the world, even to the

Americas. 10. Gordon, however, never saw the

stone in person and may not have looked closely enough at the Decalogue Stone to notice that it

could not be Samaritan.

First, a mezuzah contains the Shema (Deuteronomy 6:4-9),

and the Vehaya (Deuteronomy 11:13-21)

rather than a full version of the Ten Commandments. 11 Second, the Samaritan version

of the Ten Commandments is markedly different than the version found in the

Dead Sea Scrolls, LXX (Greek Old Testament), and Masoretic texts (Hebrew Old Testament). The Samaritan version says

“preserve” rather than “remember” the Sabbath day, in addition to the

Samaritan expansion that includes a command to build the temple on Mount

Gerizim. These Samaritan elements are

missing from the stone, which instead follows the Masoretic text almost

letter for letter except for a few spelling errors. And, of course there is the problem that the inscription is not

written in a homogenous Samaritan script, or even the Hebrew square script,

which most Hebrew language inscriptions used during the Byzantine Period. Fig. 4. CLICK to enlarge The Los Lunas Decalogue Stone, first made known to

the public in 1936,12 is a carving of 9 lines of text onto a

large, flattened basalt surface connected to a massive boulder. The language of the inscription is Hebrew,

and a translation of the text reveals that the inscription gives a summary

form of the Ten Commandments from the Masoretic text of Exodus 20:2-17. The number of characters per line from

top to bottom is as follows: 28, 21, 28, 21, 28, 29, 25, 25, 10. The first 3 lines are extremely close

together, almost touching, while the final 6 have a space of about a letters

length in between each line. This is

due either to a blatant error that will be discussed later, or to an

adjustment by the inscriber so that the text would better fill the rock face.

The spacing between words and

letters is somewhat inconsistent, although not to the point where it presents

difficulty in discerning one word from another. The letters themselves are fairly uniform, but do reveal it was

not a practiced hand that wrote them.

The form of the script is not homogenous—the author employed several

scripts that are from several different time periods and at least two

distinct languages (this will be discussed later). Looking at the stone and examining the form of the inscription,

it is apparent that a scribe was not the author and the inscription was not

well planned out. (Compare with a probable

earlier artifact from México studied by Alexander von Humboldt) A

decipherment and translation of the stone follows: (3=alef [ א], ‘=ayin [ ע], $=shin [ ש],

x=het [ ח], c=tsade [ ([צ 1) 3nky yhwh 3lhyk 3$r

hwc3tyk m3rc אנכי יהוה

אלהיכ אשר

הוצאתיך

מארצ I am YHWH your God who

brought you out of the land 2) l3 yhyh 3lhym 3xrym

‘l phny לא יהוה

אלהים אחרים

על פהני You will not have other

gods before [spelling error] Me 3) mcrym mbyt ‘bdym

-> l3 t’$h lk psl l3 t$3 מצרים

מבית עבדים

לא תעשה לך

פסל לא תשא Of Egypt from the house

of slavery -> You will not make for yourself an idol. You will not take 4) 3t $m yhwh l$w3. z3kwr 3t ywm את שם יהוה לשוא זאכור את יום 5) h$btm lqd$w. kbd 3t 3byk w3t 3mk lm’l השבתם לקדשו כבד את אביך ואת אמך למעל Of the rest (shabbat)

to keep it holy. Honor your father

and your mother in order that [spelling error] 6) y3rkwn ymyk ‘l h3dmh

3$r yhwh 3lhyk יארכון

ימיך על

האדמה אשר

יהוה אלהיך Your days may be prolonged

upon the land which YHWH your God 7) Ntn lk. L3 trcx.

L3 tn3p. L3 tgnb. L3 נתן לך לא

תרצח לא תנאף

לא תגנב לא Gave to you. You will not murder. You will not commit adultery. You will not steal. Not 8) T’nh br’k ‘d

$kr. L3 txmd 3$t r’k. תענה ברעך עד שכר לא תחמד אשת רעך You will (not) answer

deceptively [spelling error] against your neighbor. You will not covet the wife of your neighbor. 9) Wkl a$r lr’k. וכל אשר

לרעך Or anything, which

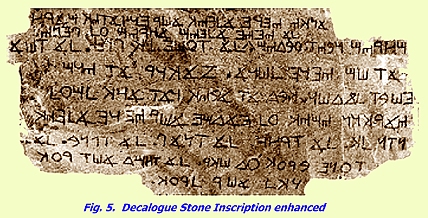

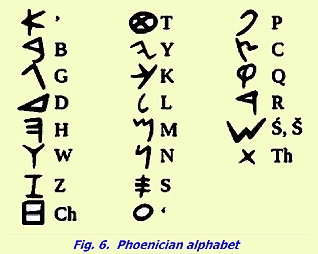

belongs to your neighbor. Fig. 5. CLICK to enlarge CLICK to enlarge The Inscription Characteristics The inscription, while often

thought to be written in “Paleo Hebrew,” or “Phoenician”, is actually a

mixture of multiple Semitic scripts with a few Greek characters. 13,14,15,16,17 Fig. 6. CLICK to enlarge For anyone familiar with Semitic

inscriptions, a first look at this inscription immediately gives the

impression that it is a poor forgery because it is not comparable to any

other Semitic inscription discovered.

This is due not only to the odd mixture of scripts, but also because

of the appearance of the characters themselves. Yet, if this inscription was made in the late 19th or early 20th century, near the time

of its 1936 discovery, the mixture of letters may be explained by the lack of

extensive knowledge about the Phoenician script. The Phoenician script was

re-discovered in 1855, and a transcription and translation from the

Phoenician sarcophagus of Eshmunazar II at a site near Sidon was published in

the June 15, 1855 New York Times, while a facsimile of the inscription

itself was published in the July 1855 edition of United States Magazine. Other scripts present in the inscription

were known at least by the end of the first decade of the 20th century. Alternatively, the mixture of letters may

be explained by the inscriber’s purposeful intent to create a more mysterious

inscription. The extensive assortment

of character forms is certainly unique and draws interest to the inscription

on those grounds alone.

The following evaluation of the characters present in the inscription

was done by means of comparing numerous photographs, drawings, and charts. 18 In general, the

letterforms on the Decalogue

Stone resemble the Phoenician

script and its immediate descendents, with a few replacements and

modifications, notably archaic Greek 19 This use of a modified Phoenician script

suggests the inscriber was attempting to emulate stone inscriptions from the

Iron Age, at least partially.

However, an obvious general form disagreement can be seen between the Decalogue Stone and ancient

inscriptions written with the Phoenician alphabet—the variance in the slope

of the letters. On the Decalogue Stone, the backs of the

letters that have a horizontal line are aligned straight up and down at a

90-degree angle to the line. In

contrast, the backs of many letters with horizontal line are written at a

sloping angle in ancient Semitic inscriptions written in the Phoenician

script, while letters in ancient Greek inscriptions are characteristically

straight. 20 Additionally,

inscriptions using the Phoenician alphabet from the Iron Age also have long

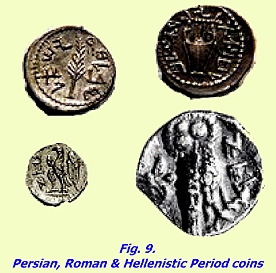

tails on many of the letters, which the letters of the Decalogue Stone lack. On the Decalogue Stone, the form of the

letters Alef, Bet, Gimel,, Nun, Ayin, Peh, and possibly Kaf and Waw could be

assigned to the Phoenician script, also used for archaic or paleo-Hebrew

(roughly 11th

to

6th

century

B. C. E.), although this would not be the hand of a trained and experienced

scribe. 21. The letter Heh follows a form from

the Roman period found on coins from the area of Judah between the Persian

and Early Roman Periods (4th century B. C. E. through the 2nd century A. D. 22. Fig. 9. CLICK to enlarge The letter Waw is somewhat similar

to the Phoenician, but more square and thus similar to Old Aramaic forms. 23. The letter Zayin is one of the characters

that appears to be borrowed from the Zeta used in some ancient Greek

inscriptions stretching from the Archaic through the Byzantine period. 24. The letter Het looks identical to the

Greek Eta used in inscriptions from a variety of periods. Tet is not present in the inscription, and

cannot be commented on. Yod clearly

follows a Samaritan form, although with more angular strokes and without a

slope. 25. Fig. 10. CLICK to enlarge Kaf and Lamed appear to follow the

Kappa and Lambda from ancient Greek inscriptions, but reversed, although the

Kaf presented on the stone could be interpreted as a Phoenician form that

changed its orientation from slanted to straight up and down. Mem is yet another Samaritan form, but simplified

without the addition to the tail veering left. 26. Samek appears only once, but follows a

Hebrew form from Egypt, such as would be used in the 5th century B. C. E. . Elephantine Letters, or alternatively a backwards

Tsade from Phoenician inscriptions. 27. Fig. 11. CLICK to enlarge The letter Peh, as mentioned

earlier, could be classed as Phoenician or Archaic Hebrew, but also matches

Old Aramaic forms. Tsade is the

latest represented form, appearing to be Rabbinical or Rashi script type for the

final form of Tsade from the mid-second millennium A. D., but could also be

construed as a strange variant of an Aramaic form. 28. Qof is only represented once, and matches

a form from Proto-Sinaitic and Proto-Canaanite inscriptions (ca. 1500-1100 B. C. E. ), although it could

also be a corrupted version of a Samaritan Qof used in inscriptions. 29. Resh is written in the same form

as Hebrew during the Roman period as well as a Samaritan script Resh, but

could also be interpreted as a Greek Rho, reversed, much like the Kappa

present in the inscription, so this letter is a poor indicator. Shin follows the Samaritan form, but also

resembles the Omega from Greek inscriptions in the Byzantine Period. Finally, Taw is yet another letter adopted

from a wide range of Greek inscriptions.

Thus, it is apparent that the author of the inscription used an

extremely wide range of letter forms, only excluding, probably deliberately,

the commonly known square script used for Modern and Biblical Hebrew today,

which dates back in an earlier form to the Aramaic square script and began to

be used for Hebrew during the period of the Babylonian Exile. The inscriber, however, may not

have known ancient alternatives to the modern day Hebrew square script for 4

or 5 of the forms (Tet is not present, which could have been the sixth, and

Kaf is debatable), as evidenced by the adoption of either Greek script or

simply inventing a letter form that looked similar to other ancient forms

used to write Hebrew. This suggests

an incomplete knowledge of the ancient Phoenician or Archaic Hebrew script,

making substitution of other ancient forms necessary, while clearly making a

point to leave out forms that are used in modern day Hebrew. Another possibility is that the

author of the inscription intentionally mixed the Greek script forms to give

the text a more unique and puzzling character. The mixing of diverse letter forms from multiple periods,

regions, and languages is simply unprecedented for any ancient monumental

inscription. This alone argues

strongly against the authenticity of the Decalogue Stone. The final important point to remember is

that all of these letter forms used were known prior to 1936, with the latest

significant script discoveries more than 20 years before the Decalogue Stone was recorded by Hibben

30.

The inscription could certainly have been

forged, with these letterforms, by 1930 or slightly earlier. An analysis of the text reveals

some interesting features. The most

obvious is the scribal error in line 3, which is an added continuation of

line 1 and marked by an upward pointing correction arrow. The author apparently noticed after finishing

line 2 that the end of the clause from line 1 had not been completed, and so

inserted it before beginning the third sentence, along with an arrow mark

facing upwards, indicating that it should be read with a higher line. 31. Line 1 ended with a word starting with

Mem, and the next word also began with a Mem. After the first sentence, nearly all of the clauses began with

a Lamed. The inscriber could have

thought he already copied the next 3 words and simply skipped that line, only

to realize later and insert a correction.

Regardless, what this error clearly indicates is that the author of

the inscription was not familiar with Hebrew, and especially not the ancient

letterforms. The error also indicates that the

scribe was copying from a source taken to the site and not from memory. The act of stopping mid-sentence and

beginning a new one demonstrates that what was being done was simply letter

for letter and sound for sound copying.

No actual scribe would do this, as scribes are literate in the

language or languages in which they write, and would usually write out the

inscription beforehand to avoid mistakes of this nature. The last and possibly most

important aspect of this error is the presence of the upward pointing

correction arrow in the actual inscription.

This use of a correction arrow is unprecedented in ancient Semitic

inscriptions. In ancient Egypt there

were cases of scratching out a former Pharaoh’s name and replacing it with

another, but this is a completely different situation, and no use of any

correction marker was used. This

correction arrow indicates a composition of the inscription outside of

antiquity, and suggests composition in the time of typeset or typewriters,

certainly fitting of an early 20th century professor.

The case for a combination of both

a copying error and limited familiarity with Hebrew can be made when various

misspelled words are analyzed. For

example, the last word in line 2, copied as phny, adds a Heh to the

word. If the copyist had just read

the word off the Masoretic text, or simply had a transcriptional copy of the

9 lines to be inscribed, an error from vocalization to writing would be

easily explained. Reading pa-nay and

then thinking out the sounds could easily translate into writing

pah-nay. Another error like this

occurs in line 4, when “zakor” is written with an Alef following the

Zayin. If reading a transcription of

the Masoretic text, or even the vowel pointed Masoretic text, it would be

easy accidentally to insert a “vowel” in the form of Alef into the word if

the copyist’s native language writes vowels.

In line 5, lema’an is written as lema’al, indicating a misreading of

the final Nun for a Lamed. While

lema’an means “in order that,” a very common word, and is found in the

commandment in Exodus 20:12, lema’al is nonsense and is an obvious

error. This error likely arose from

the inscribers misreading of final Nun in the Masoretic text for a Lamed,

since the forms are similar in the modern square script, but Nun and Lamed in

the Phoenician script are quite distinct. In line 8, Shaqer is written

Shkr—a confusion of the Kaf and Qof.

For a non-Hebrew speaker, this is an easy error to make when copying

and thinking of the sounds while inscribing.

This error also suggests the possibility that the Masoretic Hebrew

text was first transcribed into Latin characters, then reproduced in the

various scripts present on the stone. The analysis indicates that the

text was simply transferred from the Masoretic text, in incomplete form, into

ancient letter forms with little preparation and care. It further indicates that the author did

not have a good understanding of Hebrew, if any beyond knowing sounds for the

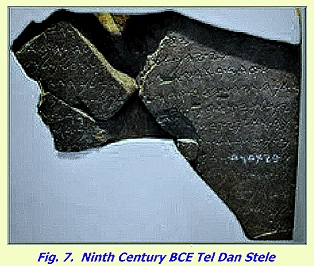

letters. Finally, although Barry Fell

claims in his article about the Decalogue Stone that the punctuation

matches that of ancient inscriptions, his conclusion is incorrect. 32. Examining ancient Semitic inscriptions

such as the Tel Dan Stele or the Mesha Stele shows that the alleged

“punctuation” marks present in Semitic inscriptions are actually word

dividers, not “periods. ” These dots at the bottom of the line in the Decalogue Stone also hold a different

position from the word divider dots in the middle of the line for Semitic

inscriptions. Instead, the Decalogue Stone uses modern

punctuation methods by placing periods at the end of sentences, which further

indicates its modern composition. Concerning the method of

inscription, patina, and angle of the stone, little can be said. Any definitive clues as to the age that

would be indicated by patina have been wiped away because of exposure to the

weather and the thousands of visitors that have touched, tampered with, and

even vandalized the stone (line 1 has been nearly scratched out). The appearance of the inscription looks

recent, but this evaluation cannot be used as primary evidence that the

inscription is from the recent past because of the conditions under which the

inscription has been subjected. The inscription rests at a strange

angle on “a boulder weighing an estimated 80 to 100 tons and is about eight

meters in length. Nine rows of 216

characters were chiseled at a 150 degree angle into the north face,” although

the ground at the base of the stone is quite flat. 33. Either the entire boulder has shifted

over time, the inscriber wrote it at that angle because it would give the

appearance of age, or because of the convenient shape of the rock section

where the inscription was placed, the inscriber decided it would look best

lining up with the square shape of the rock section. The method of the inscription

appears to be use of a chisel for the letters themselves. A small chisel, tapped lightly or even

used to scrape at times, would be the most likely method judging from the

short depth of the incisions into the rock.

No true round shapes, though prolific amounts of extremely angular shapes

are found indicate a somewhat large tool and an unpracticed hand. However, the method used to

flatten the surface before the inscription is perhaps the most interesting

physical aspect of the Los Lunas Decalogue Stone. Judging from the depth of the cuts into

the stone, at least two inches at some points, and the stress lines left from

this chipping away, a very large and strong tool must have been used for this

process. The stress fracture lines created

by creating a flat rock surface are generally at least two inches apart. The stone, basalt, is quite strong. It might be that a chisel made with a

strong metal such as iron or steel, along with a large hammer, or possibly

even a sledgehammer with a triangular point, made for breaking rocks, was

used for creating a flatter surface on which to write. These tools are fairly modern, and would

have been the tools of choice in the early 20th century when the

inscription was first seen. The above evaluation of the Los Lunas

Decalogue Stone suggests that it was

not composed by a professional scribe in antiquity, but (a) composed by

someone with a limited or no knowledge of Hebrew, (b) who did not follow the

form of any other known ancient Semitic inscription, (c) who positioned the

stone in an implausible location for a monumental inscription; further, (d)

the inscription was written after the rediscovery of the Phoenician script in

the late 19th

century,

and (e) was made with modern tools.

Even more, (f) the initial discoverer of the inscription, Frank

Hibben, had a questionable reputation because of at least three incidents in

his career in which he claimed to have made radical discoveries that had no

supporting evidence. Hibben also was

not a specialist in Semitics or the Ancient Near East, but conveniently lived

nearby as a professor of archaeology at the University of New Mexico. Thus, the evidence leads to the conclusion

that the Decalogue Stone is a creation of the

late 19th

or

early 20th

century

by someone aware of the Mexican hieroglyphics

depicting The Ten Commandments. |

|

Footnotes: (All Photos enhanced and sharpened from originals) Titus Kennedy earned a B. A. from Biola University, M. A. from the University

of Toronto in Near Eastern Archaeology, M. A. and in Biblical

Archaeology from the University of South

Africa. He is pursuing a Doctorate in Biblical

Archaeology at the University of South

Africa. You may reach

Titus at titusm@gmail. com. Mark

R. Perkins earned a B. A. from Azusa Pacific University and M.

Div. from Talbot School of

Theology. He is pastor of

the Front Range Bible Church in

Denver, CO. You may reach Pastor Mark

at frontrangepastor@gmail. com. 1. Perkins, Dixie L. “New Mexico’s Mystery Stone,” Best of the West, Tony Hillerman,

ed. 1991 (New York: Harper Collins),

3-5. 2. Dawson,

Jerry and Judge, William J.

“Paleo-Indian Sites and Topography in the Middle Rio Grande Valley of

New Mexico,”The Plains Anthropologist 14:44

(1969): 149-163. 3. Carroll,

Michael P. “The Debate over

a Crypto-Jewish Presence in New Mexico: The Role of Ethnographic Allegory and

Orientalism,” Sociology of Religion 63:1

(2002): 1-19; 2, 8-9. 4.

Nibley, Hugh W. Teachings of the Book of Mormon, Semester

2, Lecture 30, Mosiah 6. Maxwell

Institute, Provo, Utah, 1988-90. 5.

http://www.

nmstatelands. org/Permits. aspx. Hibben graduated from Princeton in 1933, and

then in 1936 received a master’s degree in zoology from the University of New

Mexico, firmly placing him in the area in 1936. 6.

Bliss (1940a). “A Chronological Problem Presented by

Sandia Cave, New Mexico. ” American

Antiquity (Society for American Archaeology) 5 (3): 200–201. 7.

Nature

426 (27 November 2003) 374. 8. The Epigraphic Society

is a club of amateur epigraphers who occasionally publish collections of

papers. It was founded in 1974,

primarily by marine biologist Barry Fell. 9. Tabor, James D. “An Ancient Hebrew Inscription in New

Mexico: Fact or Fraud?” United Israel

Bulletin Vol. 52, Summer

1997, 1-3. 10. Gordon, Cyrus,

“Diffusion of Near East Culture in Antiquity and in Byzantine Times,” Orient 30-31 (1995), 69-81. 11. The Shema is so named because it begins with

the Hebrew command “Hear!” The Vehaya begins

with the Hebrew phrase “And it will be. ” Both passages are an important part

of Jewish and Samaritan prayer. 12.

http://www. nmstatelands.

org/Permits. aspx.

Although there are claims that Hibben discovered the inscription in

1933, the first documented discovery is 1936. The name of YHWH for

nothingness (in vain). Remember

[spelling error] the day. 13. http://www. nmstatelands.

org/default. aspx?PageID=127.

Accessed August 17, 2009 14.

http://www. ancient-hebrew.

org/15_loslunas. html.

Accessed August 17, 2009 15.

http://en. wikipedia.

org/wiki/Los_Lunas_Decalogue_Stone Accessed August

17, 2009 16.

Deal, David Allen, Discovery

of Ancient America, 1st ed. , Kherem La Yah Press, Irvine CA,

1984; 3-4. 17.

http://www. econ. ohio-state.

edu/jhm/arch/loslunas. html. 18. The included photos show

some comparisons of letter forms discussed.

For general guidelines on analyzing inscriptions; cf. Demsky, Aaron. Reading Northwest Semitic Inscriptions. Near

Eastern Archaeology 70:2 (2007), 68-74. 19. Healy, John F. Reading

the Past: The Early Alphabet.

Berkeley: University of California, 1990; 29, 37. 20. Cf. stone inscriptions as the Ahiram

Sarcophagus, Sarcophagus of Eshmunazar II, Tel Dan Stele, Mesha Stele, and

Siloam Inscription. 21. Cf. The Ahiram Sarcophagus, the Gezer

Calendar, the Tel Dan Stele, the Mesha Stele, the Siloam Inscription, the

Shebna Lintel, the Ekron Inscription, the Stele of Zakkur, and others from

the Iron Age. 22. Cf. especially the Yehud coins, but also

Hasmonean and Judean revolt coins. 23.

Mykytiuk, Lawrence

J. Identifying

Biblical Persons in Northwest Semitic Inscriptions of 1200-539 B. C. E. .

E. Boston: Brill,

2004. Fig. 8, 114. 24.

The Greek Zeta sometimes

varied in form, but the most common form in inscriptions across all

time-periods resembles that on the Decalogue

Stone, which is also the same form as modern Greek. 25.

The stone inscription of

the Samaritan Ten Commandments from the Byzantine or early Islamic Period,

housed in the Living Torah Museum, or the Samaritan Mezuzah inscriptions from

the 6th to 7th

centuries AD, are excellent comparisons. 26.

Again, cf. the Samaritan above referenced Samaritan

inscriptions. 27.

Although this is not a

stone inscription, it was the closest parallel found. Alternatively, the possibility of the

letter being crafted after backwards Tsade could indicate another mistake by

the inscriber. 28.

Lidzbarski, Mark, Letter

Chart in Appendix to Gesenius, H. F. W.

Genesius’ Hebrew Grammar. Oxford, 1922. ; Healy, 29. 29.

Naveh, Joseph. “Some Considerations on the Ostracon from

‘Izbet Sartah. ” Israel Exploration

Journal 28:31-35.

Fig. 1, 31. 30.

Torrey, Charles C. (1925), “The Newly Discovered Phoenician

Inscription,” New York Times, June

15, 1855, 4. “The Ahiram Inscription of Byblos,” Journal of the American Oriental Society, 45:269–279. Dussaud, René, Syria 5 (1924:135-57). 31.

This phenomenon could be

due to a scribal error such as homeoarchy or haplography. 32. Fell,

Barry; “Ancient Punctuation and the Los Lunas Text,” Epigraphic Society, Occasional Publications, 13:35, 1985. 33. http://www. nmstatelands. org/default. aspx?PageID=127.

Accessed August 17, 2009. |