Women in Philosophy:

Quantitative Analyses of Specialization, Prevalence, Visibility, and

Generational Change

Eric Schwitzgebel

Department of Philosophy

University of California

at Riverside

Riverside, CA 92521-0201

eschwitz

at domain ucr.edu

Carolyn Dicey Jennings

School of Social

Sciences and Humanities

University of California

at Merced

Merced, CA 95343

cjennings3

at domain ucmerced.edu

February 12, 2016

Women in Philosophy:

Quantitative Analyses of Prevalence, Visibility, and Generational

Change

Abstract:

We present several quantitative

analyses of the prevalence and visibility of women in moral, political, and

social philosophy, compared to other areas of philosophy, and how the situation

has changed over time. Measures include

faculty lists from the Philosophical Gourmet Report, PhD job placement data

from the Academic Placement Data and Analysis project, the National Science

Foundation’s Survey of Earned Doctorates, conference programs of the American

Philosophical Association, authorship in elite philosophy journals, citation in

the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy,

and extended discussion in abstracts from the Philosopher’s Index. Our data strongly support three conclusions:

(1) Gender disparity remains large in mainstream Anglophone philosophy; (2)

ethics, construed broadly to include social and political philosophy, is closer

to gender parity than are other fields in philosophy; and (3) women’s

involvement in philosophy has increased since the 1970s. However, by most measures, women’s

involvement and visibility in mainstream Anglophone philosophy has increased

only slowly; and by some measures there has been virtually no gain since the

1990s. We find mixed evidence on the

question of whether gender disparity is even more pronounced at the highest

level of visibility or prestige than at more moderate levels of visibility or

prestige.

Word Count: about 8000 words, plus 5

tables and 3 graphs

Women in Philosophy:

Quantitative Analyses of Specialization, Prevalence, Visibility, and Generational

Change

1.

Introduction.

Women are half of the population, but

they do not occupy half of all full-time university faculty positions, publish

half of all academic journal articles, nor constitute half of the highest

social status members of academia.[1] The

last several decades have seen substantial progress toward gender parity in

most disciplines, but philosophy remains strikingly imbalanced in faculty

ratios and in citation patterns in leading philosophical journals.[2] The

persistent gender imbalance in philosophy is particularly noteworthy because

(a) feminism is an important subfield within philosophy and many philosophers

explicitly identify as feminist, suggesting that the discipline ought to be a

leader rather than a laggard in addressing gender issues; (b) most of the

humanities and social sciences have shifted much closer toward parity than has

philosophy, leaving philosophy with gender ratios more characteristic of

disciplines superficially very different, such as engineering and the physical

sciences; and (c) some measures suggest that progress toward gender parity in

philosophy has stopped or slowed since the 1980s.[3]

Previous work in the

sociology of academia suggests that gender ratios differ substantially between

subfields within academic disciplines, possibly with women more common in

subfields regarded as less prestigious.[4] Preliminary data suggest

that ethical, political, and social philosophy might be closer to gender parity

than other areas of philosophy, and many of the most prominent women

philosophers of the past hundred years have been known primarily for their work

in these areas (e.g. Simone de Beauvoir, Hannah Arendt, Philippa

Foot, Martha Nussbaum, and Christine Korsgaard).[5]

Below we present data

from several sources on the prevalence and visibility of women in philosophy

over the past several decades. We focus on philosophy in the English-speaking

world, especially the United States. There is, we believe, a sociological

center of dominance in philosophy as practiced at universities in the United

States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia. We will call this

sociological center mainstream Anglophone

philosophy, without intending any judgments about the quality of mainstream

Anglophone philosophical work compared to work in other languages or traditions

or outside of this sociologically defined mainstream. Visibility in mainstream

Anglophone philosophy can be measured in a variety of ways, among them

membership in highly ranked departments in the Philosophical Gourmet Report; publication

in and citation in journals that are viewed as “top” journals (e.g. Philosophical Review and Ethics, which tend to lead

journal-ranking polls on Anglophone philosophy blogs with large readerships

among professional philosophers); and citation in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

We aim to test four

hypotheses:

(1)

Confirming other recent work, gender disparity remains

large in mainstream Anglophone philosophy, across several methods of measuring

women’s involvement or visibility.

(2)

Ethics, construed broadly to include social and

political philosophy, is closer to gender parity than are other areas of

philosophy.

(3)

The gender disparity in mainstream Anglophone

philosophy is even more pronounced at the highest levels of visibility or

prestige than at moderate levels of visibility or prestige.

(4)

Women’s involvement and visibility in mainstream

Anglophone philosophy has increased over time, but only slowly in the past few

decades. (We would regard a 10% increase over 40 years to be slow, whether it

is from 5% to 15% or 25% to 35%.)

2.

Analysis of the 2014 Philosophical Gourmet Report.

The Philosophical Gourmet Report

(PGR), edited by Brian Leiter and Berit Brogaard, is a survey of philosophy

faculty quality or reputation. Every few years hundreds of “research active”

philosophers are asked to numerically rate overall faculty quality at dozens of

PhD programs – programs that in the view of the editorial board stand a

reasonable chance of being among the top 50 in the U.S., the top 15 in Britain,

the top 5 in Canada, or the top 5 in Australasia. These numerical ratings are

averaged to create overall rankings.[6]

We examined the

faculty lists provided to the PGR evaluators in 2014 for all departments in the

United States (59 total departments), removing from the list faculty listed as

“cognate” or “part-time.” Subfield was determined by area of specialization

information available on department or faculty websites and sorted into four

categories: “Value Theory”, “Language, Epistemology, Mind, and Metaphysics”

(LEMM), “History and Traditions”, and “Science, Logic, and Math”. These

categories were chosen using the PhilPapers Taxonomy

from the PhilPapers Categorization Project (combining

the categories of “History of Western Philosophy” and “Philosophical

Traditions” into “History and Traditions”), and areas of

specialization were fit into subfields based on that taxonomy.[7]

Faculty whose work crossed subfields were classified based on their first

listed area of specialization. For example, if a faculty member listed “Ancient

Philosophy” and “Virtue Ethics” in that order, she would be classified under

History and Traditions; if she listed “Kant’s ethics”, she would be classified

under Value Theory. Gender was classified based on name, website photo, and

personal knowledge. In no case was gender judged to be intermediate or

indeterminable.

Of the 1104 analyzed

faculty, 25% (271) were women, a number roughly consistent with previous

estimates that women are about 21% of U.S. faculty in philosophy overall. The

distribution of women and men across different subfields was significantly

different (χ2 [3] = 31.0, p

< .001), as shown in Table 1. If we confine the analysis to the 258 faculty

at the top twelve[8]

ranked universities according to the 2014 PGR, the percentage of women is about

the same: 61/258 (24%).[9]

Table 1: Percentage of faculty in each

subfield who are women, among 2014 PGR-ranked faculty in the United States.

Subfield #

women # men % women

Value Theory 90 176 34%

Language, Epistemology, Mind, and

Metaphysics 65 266 20%

History and Traditions 78 185 30%

Science, Logic, and Math 38 206 16%

Value theorists constituted 22%

(56/258) of faculty at the top-twelve rated universities and 25% (210/846) of

faculty at the remaining universities, a difference in proportion that was not

statistically significant (z = -1.0, p = .31, all z’s two-tailed unless

otherwise specified). The mean PGR rating was 3.02 for faculty in the Value

Theory subfield and 3.12 for faculty in all other subfields, a statistically

marginal trend (t = -1.9, p = .06).

Table 2 displays the

data by academic rank. The different distributions of women and men in these

academic ranks was statistically significant (χ2

[2] = 23.1, p < .001), with a higher proportion of women at the rank of assistant

and associate professor than at the rank of full professor. The trend was

evident both in Value Theory (43% women among faculty at assistant rank, 55%

among faculty at associate, 26% among faculty at full) and in all other

subfields combined (36%, 22%, 18%).

Table 2: Percentage of faculty at each professional

rank who are women, among 2014 PGR-ranked faculty.

Rank # women #

men % women

Assistant professor 58 97 37%

Associate professor 72 180 29%

Full professor 141 556 20%

These data thus

support Hypothesis 1: At 25% women faculty, gender disparity among faculty at

PGR-ranked U.S. PhD programs is large and approximately in line with previous

estimates. Hypothesis 2 is also supported: Women were not proportionately

represented among the subfields, with the highest proportion in Value Theory

(34%) and the lowest proportion in Science, Logic, and Math (16%). Hypothesis

3, however, is not supported: 2014 PGR-rated PhD programs in the United States

do not appear to contain a lower percentage of women than U.S. faculty as a

whole, nor did we find evidence that the top 12 programs contain

proportionately fewer women than the other rated programs. The difference in

distribution between men and women with respect to faculty rank is consistent

with an increase in women recently entering the faculty (Hypothesis 4) but is

also consistent with higher attrition rates or lower promotion rates for women.

3. Analysis of PhD Job Placement Data,

2012-2015.

The Academic Placement Data and

Analysis project (APDA), directed by Carolyn Dicey Jennings, maintains

placement information for PhD graduates from 146 English-language philosophy

programs around the world (the data for 128 of which are included here). This

information has been largely provided by the graduates themselves, placement

directors, and department chairs. Collected information includes name; area(s)

of specialization; graduation year and program; and placement institution,

type, and year. While the APDA database is the most complete record of

placement information for the field of philosophy, it nonetheless incomplete

for graduation years before 2012 and for some categories of data, such as

non-academic placements and temporary placements. Gender was determined by

first name, using an online gender probability generator (genderize.io) and the

cutoff of .6 probability to assign gender. For those

below the cutoff, gender was classified based on website photo and personal

knowledge. In 2% of cases (40/1802) gender was judged to be indeterminable or

non-binary. Those individuals were

excluded from further analysis. Area of specialization was grouped using the

same system used in section 2.[10]

Among recent

graduates with recorded academic placements (graduating between 2012 and 2015),

28% were women (424/1509), which is statistically somewhat higher than most

estimates of the overall percentage of women in philosophy faculty positions in

English-speaking countries (the 95% confidence interval of 424/1509 is 26% to

30%). Among recent graduates with permanent academic placements, 32% were women

(231/723, CI 29% to 35%), also higher, though not higher than the proportion of

women we found at the assistant professor rank in the PGR-ranked universities

discussed above (37%).

Area of

specialization was not consistently provided, so we had to leave subfield

unclassified for 25% of the dataset (449/1762). The most common reason for

missing subfield information was that the graduating program did not track this

information. Missing subfield information did appear to track PGR rating: Field

information was missing for 31% of individuals from unrated programs, compared

to 23% from PGR-rated programs (169/539 vs. 280/1223, z = 3.8, p < .001);

and among the rated programs, the mean PGR rating was 3.04 for graduates with

missing subfield information and 3.15 for all other graduates (t = -2.5, p =

.01). However, the difference between

the proportion of women and men with missing subfield information was not

statistically significant (23% vs. 26%, z = -1.5, p = .12). For those with

classified subfields, area of specialization was significantly different by

gender, but not as strikingly so as among PGR faculty (χ2 [3] = 8.4, p = .04). See Table 3.

Table 3: Percentage of graduates

in each subfield who are women, among 2012-2015 graduates in APDA database.

Subfield #

women # men % women

Value Theory 143 287 33%

Language, Epistemology, Mind, and

Metaphysics 92 288 24%

History and Traditions 94 231 29%

Science, Logic, and Math 48 130 27%

We did not see

evidence of gender differences based on the 2014 PGR rating of the PhD-granting

university. Among universities rated in the 2014 PGR,

the mean rating of the granting university was virtually the same for women and

men (3.14 vs. 3.12, t = -0.3, p = .74) as was the proportion of women among

graduates from PGR rated programs (28% of both groups).

Among PGR-rated

programs, we did not see a statistically significant tendency for certain subfields

to associate with more highly rated graduating departments (F [3, 939] = 1.2, p

= .30). However, graduates from unrated programs were less likely to specialize

in Language, Epistemology, Mind, and Metaphysics (14% vs. 35%) and more likely

to specialize in History and Traditions (45% vs. 17%) than were graduates from

rated programs; but the rates of specialization in Value Theory were similar

for unrated and rated institutions (36% vs. 31%).

Hypotheses

1 and 2 are thus supported: Gender disparities are large in this dataset, with

women disproportionately specializing in Value Theory. Hypothesis 3 is again

not supported: The percentages of women do not appear to change at the highest

levels of status. These data are consistent with, and perhaps support,

Hypothesis 4: If 28% of recent PhD graduates with recorded academic placements

are women, this might reflect a trend toward decreasing gender disparity, if

women comprise fewer than 25% of existing faculty in the relevant range of

hiring departments – though the unsystematic geographic mix of hiring

departments makes a strict comparison impossible.

In this section and

the last, we categorized philosophers according to the PhilPapers

taxonomy, focusing on its Value Theory subfield. Although most philosophers

working in Value Theory specialize in ethics broadly construed to include

applied ethics, normative ethics, meta-ethics, social and political philosophy,

and law, some work on aesthetics (in this data set, 18 out of 430 value

theorists), and others work on gender, race, and sexuality (14 out of 430) which

often but not always fits within ethics broadly construed. Given the small

numbers in each of those groups, this labeling issue does not make much overall

difference to the results above.

However, in the remaining sections we focus on ethics broadly construed,

excluding aesthetics and including gender, race, and sexuality only when those

directly pertain to ethics broadly construed.

4.

Survey of Earned Doctorates, 1973-2014.

The Survey of Earned Doctorates (SED)

is a questionnaire distributed by the U.S. National Science Foundation to

doctorate recipients at all accredited U.S. universities, which draws response

rates over 90% annually. Publicly available data are published on the NSF

website for 2009-2014. Upon request, the NSF supplied us with data going back

to 1973. Available data include gender by subfield, with one subfield being

“philosophy” (1973-2014) and another (much smaller) “ethics” (2012-2014). For

analysis, we merged these two subfields. The large majority of philosophy PhD

recipients in the United States aim to enter careers teaching philosophy at

either the university or college level.[11]

For 2009-2014, 29% of

“philosophy” and “ethics” SED respondents who reported gender were women, in line

with the 28% of PhD placements who were women in a similar period in the

Anglophone-dominated (but not exclusively U.S.) dataset analyzed in Section 3

(811/2840, CI 27%-30%). In the same period, women received 51% of PhD degrees

in the humanities as a whole (16,330/31,734). However, philosophy was not

entirely alone among the humanities in its gender disparity: Among the 33

humanities categories, “music theory and composition” was even more gender

skewed at 22% women (127/587). The third most skewed humanities discipline was

“religion/religious studies, Jewish/Judaic studies”, at 34% women (646/1876).

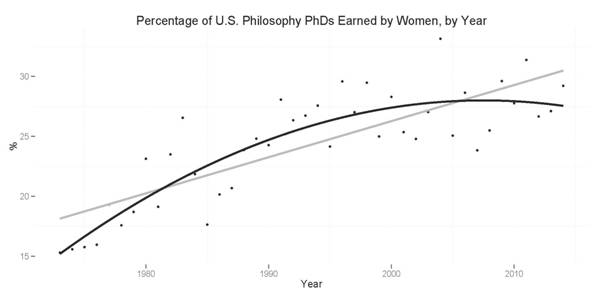

Figure 1 shows

historical trends back to 1973.[12] A

linear regression predicting percentage of doctorates awarded to women by year

of award is significantly different from zero slope (t = 8.6, p < .001) but

the slope is still rather flat, with an increase of only 0.30% per year. Since

we had hypothesized that change in disparity might be slowing, we also tried

fitting a quadratic curve, displayed in black in Figure 1. The quadratic curve

does indeed fit much better than the linear, with a difference of 11.40 in the AICc scores (which penalize models with more parameters):

The AICc relative likelihood of the quadratic vs. the

linear is .996 to .004. In other words, the visually apparent flattening is

highly unlikely to be chance variation in a linear trend. (We use the quadratic

only to test for flattening, not to extrapolate beyond the measurement years.)

One intuitive way to see the slowing is to aggregate the data by decade: in

1973-1979 17% of U.S. philosophy PhDs went to women; in the 1980s, 22%; in the

1990s, 27%; in the 2000s, also 27%; and in 2010-2014, 28%.

Figure 1: Based on SED data. The gray line

is the best linear fit. The black line is the best quadratic fit.

These data confirm

Hypothesis 1: Gender disparity in philosophy remains large. Hypothesis 4 is

also confirmed: Disparity has decreased, but this decrease has slowed over

time.

5. American Philosophical Association

Gender Data.

The American Philosophical Association

(APA) is the main professional association of philosophy professors in the

United States (with substantial Canadian and other international involvement). In

2014 and 2015 it conducted demographic surveys of its members. In 2014, 4152

out of 9180 members responded with gender information (45% response rate).[13]

Among those, 983 (24%) were women and 1 responded with “something else.” In

2015, 3362 out of 8975 members responded (38% response rate), 805 (24%) women,

4 “something else”, and 19 “prefer not to answer.” Although these numbers are

similar to other estimates that support Hypothesis 1, reasons for caution

include (a) that women may be more or less likely than men to be APA members or

(b) that women may be more or less likely to respond to such a demographic

survey.

6. Appearance on American Philosophical

Association Programs, 1955-2015.

Long term temporal trends might also

be evident from patterns of participation in meetings of the American

Philosophical Association. By examining the roles women play in the program

(e.g. invited speaker, commenter, session chair), we

can also explore questions about prestige and visibility.

The APA contains

three divisions: Eastern, Central (formerly Western), and Pacific, each of

which meets separately, with participants from across the world. There is no

primary meeting of the entire APA. Meetings consist of a “main program”

organized by program committees and a “group program” separately organized by

subgroups of philosophers. Some of the main program sessions are “special

sessions” on issues like the teaching of philosophy or on the status of women

or ethnic minorities. The remaining sessions are focused on research topics in

philosophy. “Colloquium” sessions normally consist of submitted and refereed

papers, often by less senior faculty. Some “symposium” sessions are similarly

refereed, while others are invited. “Colloquium” sessions typically have only

one commentator; “symposium” sessions have longer talks with more than one

commentator. Other sessions are invited, normally featuring senior, visible

people in the profession. Some sessions are named, and typically regarded as

especially prestigious, such as the “Dewey Lectures” or the Presidential

addresses (each division has its own President). Also notable are “Author Meets

Critics” sessions, which feature a panel of invited critical treatments of a

recent book and a reply by the author. Every session has a “chair”, which

(despite the title) is a less visible and prestigious role than speaking or

commenting, normally confined to keeping the session on schedule and managing

the question queue.

We examined main

session programs for all three divisions from five sample years: 1955, 1975,

1995, and 2014-2015, excluding special sessions.[14] The gender of every program

participant was coded based on first name or personal knowledge, excluding

cases judged to be ambiguous, such as where only first initial was provided,

where the name was gender ambiguous (e.g. “Pat”), or names where gender

associations were unknown to the coder (e.g. “Lijun”).

Overall, 8% (240/3180) names were judged indeterminable, with a trend toward a

more indeterminability in the 2014-2015 data (10%:

177/1703; impressionistically, due to a higher rate of non-Anglophone names).

We sorted program role into five categories in what we judged to be decreasing

order of perceived prestige: (1) named lecture, author in author-meets-critics,

or symposium speaker with at least one commentator dedicated specifically to

her presentation; (2) non-colloquium speaker not in Category 1, including

critic in author-meets-critics, (3) non-colloquium commentator, (4) colloquium

speaker or commentator, (5) chair of any session. Finally, we classified each

participant as ethics (construed broadly to include political and social

philosophy, but not including other value theory fields, such as aesthetics),

non-ethics, or mixed/excluded (including intermediate topics such as philosophy

of action and philosophy of religion without an explicitly ethical component,

and including treatments of historical figures known for contributions both in

ethics and outside of ethics if the ethical or non-ethical focus was not

explicit). Thus, we could examine temporal trends in women’s involvement in APA

programs, both in ethics and in non-ethics, and whether women are more or less

likely to serve in prestigious roles on the program.

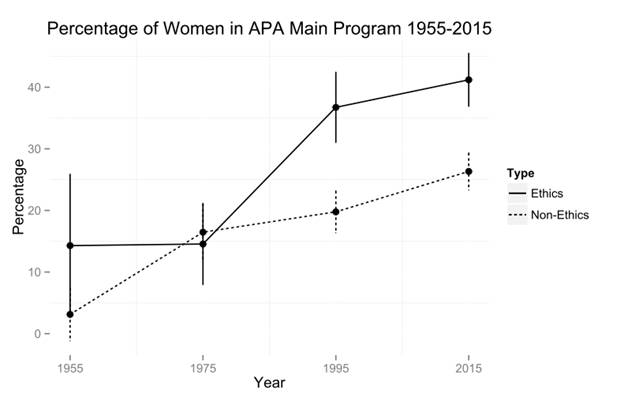

Figure 2 displays the

data on women’s overall involvement in ethics and non-ethics sessions in the

four time periods. As is evident from the figure, women’s involvement has

increased substantially since 1955 and 1975. Overall, women were 6% of program

participants in 1955 (7/121, excluding 5 indeterminable), 16% in 1975 (62/397,

excl. 20), 25% in 1995 (220/896, excl. 38), and 32% in 2014-2015 (481/1526,

excl. 177). By 2014-2015, 41% (206/500) of participants in ethics sessions were

women. The increase in women was statistically significant both for ethics and

non-ethics (correlating year 1955, etc., with gender = 1 for women and 0 for

men yields r = .18 in ethics, r = .13 in non-ethics, with both p values <

.001 [treating 2014 as 2015]). Women were statistically more likely to appear

in ethics roles than non-ethics roles in 1995 and 2015 (1955 Fisher’s exact p =

.09, two-tailed; 1975 z = -0.5, p = .64; 1995 and 2014-2015 z’s > 5.0, p’s

< .001).

Figure 1: Based on APA data. The vertical lines indicate 95% confidence

intervals.

Overall program role

data are displayed in Table 4, with 1955 and 1975 merged for presentation.

Chi-square analysis of 2014-2015 shows a statistically significant relationship

between gender and program role (χ2

[4] = 18.9, p = .001). In 2014-2015, women were more likely to appear as

invited speakers, but not in the highest prestige invitations, and as session

chairs (Categories 2 and 5), than to appear in the highest prestige lectures

and as colloquium speakers (Categories 1 and 4), but since this doesn’t map

neatly onto our initial hypothesis about prestige, and since it is not

consistent across the sampled years, we interpret the results cautiously.

Table 4: Percent of women in

different program roles, for APA meetings in sample years from 1955-2015.

Role 1955-1975 1995 2014-2015

_

Category 1 (most prestige) 5/34 (15%) 11/46

(24%) 27/99

(27%)

Category 2 4/63 (6%) 28/104 (27%)

117/314 (37%)

Category 3 8/61 (13%) 15/51 (29%)

29/96 (30%)

Category 4 38/256 (15%) 104/463 (22%) 155/597

(26%)

Category 5 (least prestige) 14/104 (13%) 62/232 (27%) 153/420 (36%)

These results compare

interestingly with the results of other measures. Overall APA main program

participation (excluding special sessions) was 32% women with a 95% confidence

interval from 29% to 34%. If the population of women in the profession is 28%

or less, as it would appear to be from our data in previous sections as well as

data from other investigators, then women are proportionately more likely to

appear in APA main programs than are men. Several past APA program committee

members have told us that they have made efforts to include more women on the

program. These data suggest that their efforts may have been successful,

perhaps especially in the invited parts of the program (all but Category 4,

which at least in recent years tends to be anonymously refereed). Another

possible explanation is greater interest in APA meetings among women than among

men.

These data confirm

Hypotheses 1 and 2 (gender disparity, but less in ethics), and provide mixed

results regarding Hypothesis 3 (that disparity is largest at the highest levels

of prestige). Hypothesis 4 is that women’s involvement has increased over time

but only slowly in the past few decades. These data confirm women’s increased

involvement. Whether the increase has been “slow” depends on whether an

increase from 16% to 32% over forty years (1975-2015) is slow.

7. Authorship in Five Elite Journals,

1954-2015.

To further examine temporal trends in visibility

at the highest levels of prestige, we examined authorship rates over time in

five elite journals. Three of the journals were Philosophical Review, Mind, and Journal of Philosophy, sometimes referred to as the “big three”

general philosophy journals. All three have been regarded as leading journals

since at least the early 20th century, and they tend to top informal polls of

journal prestige, such as polls on the Leiter Reports blog, sometimes alongside

relative newcomer Noûs

(e.g. Leiter 2013, 2015). Since these journals publish proportionately less in

ethics than in other areas of philosophy, we also include two elite ethics

journals, Ethics and Philosophy & Public Affairs, which

tend to top polls of ethics journals (e.g. Bradley 2005, Leiter 2009), although

Philosophy & Public Affairs has

only been publishing since 1972.

In December 2014, we

examined the names of all authors publishing articles, commentaries, or

responses (but not book reviews, editorial remarks, or retrospectives), in four

time periods: 1954-1955, 1974-1975, 1994-1995, and 2014-2015. (However, since

not all 2015 issues of Philosophical

Review and Journal of Philosophy

had been released at the time of data collection, we went back into late 2013

for these two journals to have a full two-year sample.) All articles in Ethics and Philosophy & Public Affairs were coded as “ethics.” Articles in

the other three were coded as either “ethics” or “non-ethics” depending on

article title or a brief skim of the article contents when the title was

ambiguous. Gender was coded based on first name or personal knowledge, or in

cases of uncertainty a brief web search for gender-identifying information such

as a gender-typical photo or references to the person as “him” or “her” in

discussions of that person’s work. In only 11 cases out of 1202 were we unable

to make a determination. We treated non-first-authors in the same manner as

first authors, but only 53 out of 1143 articles (5%) had more than one author.

Figure 3 displays the

results. Increases in the rates of women authors were statistically

significant, though small, both overall (r = .10, p = .001) and for ethics and

non-ethics considered separately (ethics r = .10, p = .03; non-ethics r = .08,

p = .04). Ethics authors were significantly more likely to be women in

1974-1975 and in 1994-1995 (26/161 vs. 13/192, z = 2.7, p = .006; 21/119 vs.

11/127, z = 2.1, p = .04), but no statistical difference was evident in the

earlier or later time samples (5/107 vs. 12/236, z = -0.2, p = .87; 18/119 vs.

14/130, z = 1.0, p = .31).

Figure 3: Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

The 2014-2015 results

are strikingly low. Merging the ethics and non-ethics for analysis (which

probably somewhat overrepresents ethics compared to

philosophy as a whole), only 13% of authors were women (32/249). This is significantly

lower than even the more pessimistic estimates of the percentage of women in

the profession, with a 95% confidence interval from 9% to 18%, and these

percentages are vastly lower than the APA percentages, especially for ethics:

In 2014-2015, only 15% of authors publishing ethics in the most elite journals

were women, despite women constituting 41% of APA ethics session participants.

In this data set, little

change is evident since the 1970s. Given the large error bars and the dangers

of post-hoc analysis, we would interpret that fact cautiously. However, these

low and flat numbers since the 1970s are also consistent with data from

2002-2007 for these same journals, compiled by Sally Haslanger (2008).

Haslanger found 12% women authors in a selection of eight elite journals, and

13% in the five journals we have analyzed.

These data confirm

Hypothesis 1, that gender disparities in philosophy are high. They provide

mixed evidence for Hypothesis 2, with significantly less disparity in ethics

than in non-ethics for two of the four sampled time periods. They support

Hypothesis 3: Authorship in one of these journals plausibly constitutes a

higher level of visibility in mainstream Anglophone philosophy than does

faculty membership (at least outside PGR-ranked departments), and at this high

level of visibility the percentage of women is lower than that in the

population of faculty as a whole. These data also support Hypothesis 4:

Disparity has decreased since the 1950s, but only slowly if at all since the

1970s.

8. Most-Cited Authors in the Stanford

Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (SEP) is widely viewed as the

premier resource for up-to-date literature reviews in mainstream Anglophone

philosophy. Our impression is that frequent citation in the SEP is a better

measure of visibility in mainstream Anglophone philosophy than are more

standard measures in the bibliometrics of other fields,

such as the ISI Web of Science database and Google Scholar. We will present

some confirmatory tests of our SEP measure below.

In summer 2014, we

downloaded the bibliographical section of every main entry from the SEP

(approximately 1400 encyclopedia entries, containing over 100,000 citations).

Looking only at first-authorship, we looked at authors who appeared at least

once in the bibliographies of at least twenty separate main entries (not

sub-entries), hand-separating authors with common names (e.g. “J. Cohen”),

hand-merging individuals who used different names in different periods of their

career (e.g. “Ruth Barcan” = “Ruth Marcus”), and

excluding authors born before 1900. In this way we generated a ranked list of

the 267 contemporary authors appearing as first author in the greatest number

of SEP front-page entries. We will call these the “most cited” authors in the

SEP. (We had been aiming for 250, but a large tie for rank 243 gave us 267

total. The full list was posted on Eric Schwitzgebel’s

blog, The Splintered Mind, and generated enough interest to result in a few

minor corrections. See Schwitzgebel 2014b for the full list.)

Partly based on

reader’s reactions, we believe this list has surface plausibility as an

approximate measure of visibility in mainstream Anglophone philosophy. The top

ten in order are David Lewis, W.V.O. Quine, Hilary

Putnam, Donald Davidson, John Rawls, Saul Kripke, Bernard Williams, Robert Nozick, and (tied) Thomas Nagel and Martha Nussbaum.

Further evidence of the validity of this method as a measure of visibility or

prominence in the target social group is: (1) similar names appear near the top

of reputational polls on philosophy blogs, such as Leiter’s

(2015b) poll of “the most important Anglophone philosophers, 1945-2000” which

lists Quine, Kripke, Rawls, Lewis, and Putnam, in

that order; and (2) a good correlation between departments’ PGR rankings and

their rankings based upon the SEP citation numbers of their faculty (Leiter

2014).

Women are

underrepresented on this list. Only one woman appears in the top 50, Martha

Nussbaum (tied for 9th). Six more fill out the top hundred: Christine Korsgaard, G.E.M. Anscombe,

Elizabeth Anderson, Julia Annas, Judith Jarvis Thomson, and Iris Marion Young.

Women constitute 10% of the total list (27/267). We classified philosophers on

this list as primarily known for their work in ethics (construed broadly to

include political and social philosophy as well as history of ethics) or not

primarily known for their work in ethics. Despite some close calls,[15]

most classifications were clear. Although women were only 6% of the

non-ethicists on this list (12/197), they were 21% of ethicists (15/70), a

difference large enough to be statistically significant even in this relatively

small sample (z = 3.0, p = .002; given the sample size and clear directional

hypotheses all proportion tests in this section are one-tailed to improve

power).

Table

5: Women among the most-cited contemporary authors in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Citation Rank ethicists non-ethicists

women men women men

1-48[16] 1 12 0 40

54-150[17] 6 22 3 67

152-267 8 21 9 78

We also noted the

birth year, usually based on biographical information available on the web, and

in a few cases estimated from other information such as year of BA, PhD, or

first publication (estimating 22 years for BA and 29 years for PhD or first

publication). The mean birth year for men was 1939, a bit earlier than women’s

mean birth year of 1945 (t = 2.4, p = .03), suggesting that women are a bit

better represented in the younger generation than in earlier generations. Based

on data from the Philosopher’s Index abstracts, analyzed in Schwitzgebel (2010;

see also below), philosophers appear to achieve peak influence around ages

55-70. If we look at philosophers born 1946 or later among the 267 most-cited

philosophers in the Stanford Encyclopedia – the most influential Anglophone philosophers

in the world, at or near the peak of their influence – 16% are women (17/107),

compared to 6% in the earlier generation born 1900-1945 (10/160, z = 2.4, p =

.008). Of these post-war women, 59% are ethicists (10/17), compared to only 21%

ethicists among men (19/90, z = 3.0, p = .001).

These data support

all four of our hypotheses. The percentage of women is small (Hypothesis 1); it

is greater in ethics (Hypothesis 2); it is lower at the highest levels of

visibility than at more moderate levels of visibility, both within these data

(top 50 vs. the rest) and comparing these data with the prevalence of women in

the profession as a whole (Hypothesis 3); and the percentages are increasing,

though perhaps only slowly (Hypothesis 4).

9.

Analysis of “he” and “she” in Selected Philosopher’s Index Abstracts,

1970-2015.

Another measure of visibility is the

mention of one’s name in article abstracts in the Philosopher’s Index, the standard source of

English-language philosophy abstracts since 1940 (though now facing competition

from PhilPapers). Schwitzgebel (2010) defines this as

“discussion” and analyzes the temporal course of the discussion rates of

selected prominent philosophers, finding (as mentioned above) peak discussion

typically around ages 55-70.

“Extended discussion”

might be operationalized as reference at least twice in the abstract of an

article, by either name or pronoun, suggesting a very high level of attention:

an article published primarily as a treatment of another philosopher’s work.

Outside of history of philosophy, such treatments are a small percentage of

articles. The nominative pronoun might be especially telling, since its

presence suggests that the person is being referred to repeatedly in

independent clauses. For example:

Later, Nussbaum gradually reconsidered

the notion of patriotism in texts that remained largely unknown and rarely

discussed. This article begins with a brief account of her shift from cosmopolitanism to

what she terms ‘a globally

sensitive patriotism,’ and the task assigned to education within this

framework....

This suggests a possible rough and

simple measure of the rates at which women receive this sort of discussion,

compared to men: Compare the ratio of “she” to “he” in philosophy abstracts,

then remove cases in which those words are used with generic intent (e.g. “If

the agent wouldn’t have done otherwise whether or not she could have….”) or

otherwise not referring to an individual philosopher whose work is being

discussed (e.g. reference to historical leaders or third-person reference to

the author him- or herself for abstracts written in the third person).

We searched the

Philosopher’s Index for all appearances of “she” or “he” from 1970 to 2015 in a

sample of ten ethics journals and ten general philosophy journals.[18]

This yielded a total of 876 ethics journal abstracts and 1445 non-ethics

abstracts. Limitation to abstracts in which “she” or “he” refers to an individual

philosopher reduced the totals to 620 in ethics and 932 in non-ethics. An

approximate total universe of abstracts was estimated by searching for “the” in

abstract field, which yielded about 6700 hits in the ethics journals during

this period and 11,600 in the non-ethics journals – thus only about 9% of

ethics abstracts and 8% of non-ethics abstracts met the criterion for

containing extended discussion of an individual philosopher. Being mentioned

multiple times in the abstract of a journal article is a high and unusual level

of attention in mainstream Anglophone philosophy.

Gender trends by

decade are displayed in Table 4. Consistent with the data from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, at

this extremely high level of visibility the gender skew is very large,

especially in non-ethics and especially in the older generation. In the ten

selected non-ethics journals, from 1970s through the 1980s, 267 abstracts

contained extended discussion of the work of men and only 4 contained extended

discussion of the work of women. The numbers do appear to increase over time,

clearly so in the non-ethics journals (r = .14, p < .001) but with only

marginal statistical significance in the ethics journals (r = .07, p = .09).[19]

Merging the data from the 2010s, which might somewhat overrepresent

ethics relative to the profession as a whole, only 13% of the recipients of

extended discussion were women. Merging across the decades, women received

extended discussion more frequently in the ethics abstracts than in the non-ethics

abstracts (z = 3.2, p = .002).

Table 5: Extended discussion as

measured by use of “she” or “he” to refer to individual philosophers in the

abstracts of 10 selected ethics journals and 10 selected non-ethics journals,

1970-2015.

Decade Ethics Non-Ethics

#

she _ # he % she #

she # he % she

1970s 8 84 9% 4 129 3%

1980s 3 74 4% 0 137 0%

1990s 20 127 14% 9 180 5%

2000s 16 168 9% 16 213 7%

2010s 19 101 16% 27 217 11%

Given that the

philosophical canon was overwhelmingly male before the 20th century, we

conducted a second analysis removing pronouns referring to philosophers whose

primary work was done before 1900. (Frege, an

important borderline case, we classified as pre-20th century.) This resulted in

the removal of 364 abstracts (23% of the total) and did not have a large effect

on the results, with 20th-21st century women receiving 7% of extended

discussion in the 1970s (12/161) and still only 14% in the 2010s (44/305). The

95% confidence interval around this last number is 11%-19%, significantly lower

than the percentage of the women currently in the profession, but perhaps not

lower than the percentage several decades ago (see footnote 12). This data set

supports Hypotheses 1, 2, and 4: There’s a substantial gender disparity in targets

of extended philosophical discussion, more so in ethics, and with a slow

increase in the proportion of women over time. Hypothesis 3 is that the

disparity is more severe at the highest levels of visibility than at more

moderate levels of visibility. Whether this hypothesis receives support is

harder to assess, since philosophers are sometimes targeted for extended

discussion decades after their relevant work, so one might expect discussion

percentages to reflect a compromise between the percentage of currently active

women and percentages from a few decades previously.

10. Conclusion.

We began with four hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1 was that

gender disparity remains large in

mainstream Anglophone philosophy. This hypothesis was strongly supported. Women constituted 24% of U.S. PGR-ranked

faculty, 28% of recently placed PhD’s, 28% of recent philosophy PhD’s in the

U.S., 24% of APA members who reported their gender, 32% of recent APA program

participants, 13% of authors in five elite journals, 10% of the most-cited

contemporary authors in the Stanford

Encyclopedia of Philosophy, and 14% of 20th-21st century philosophers

recently receiving extended discussion in the abstracts of 20 sampled journals.

Only one measure approached gender parity: women were 41% of participants in

APA ethics sessions in 2014-2015.

Hypothesis 2 was that

ethics, construed broadly to include

social and political philosophy, is closer to gender parity than are other

areas of philosophy. This hypothesis was also strongly supported. The proportion of women in ethics substantially

exceeded the proportion in other areas of philosophy among U.S. PGR-ranked

faculty, recent job placements, APA program participants, authorship in elite

journals, highly cited authors, and targets of extended journal article

discussion. Although the difference is not statistically significant for every

time sample in every measure, across the board it is a consistent story.

Hypothesis 3 was that at the highest levels of visibility or

prestige within mainstream Anglophone philosophy, gender disparity is even more

pronounced that at more moderate levels of visibility or prestige. Evidence

for this hypothesis was mixed. Contra

Hypothesis 3, the percentage of women faculty at PGR-ranked PhD departments was

similar to the percentage in the discipline as a whole, and the percentage

among the top-12 ranked programs was also similar. Also contra Hypothesis 3,

recently placed women did not tend to receive their degrees from lower-ranked

institutions than their male counterparts; nor were they disproportionately

likely to have less prestigious roles on the APA program. However, consistent

with Hypothesis 3, women were considerably less likely to have full professor rank

in PGR-ranked PhD departments than assistant or associate rank, were a

disproportionately small percentage of authors in elite journals (13%), were a

disproportionately small percentage of most-cited SEP authors (10%; 16% among

authors born 1946 or later), and perhaps were a disproportionately small

percentage of authors recently receiving extended discussion in journal

abstracts (14%).

Hypothesis 4 divides

into two sub-hypotheses: 4a, that women’s

involvement and visibility has increased over time, and 4b, that increase has been slow in the past few

decades. Hypothesis 4a received strong

support and Hypothesis 4b received

support. The PGR data perhaps support 4a if the presence of more women at

the assistant and associate professor level than at the full professor level is

interpreted as indicating youth rather than slower rates of promotion. (It

might well reflect both.) The APA data strongly support 4a but perhaps not 4b:

Women’s participation in APA programs has increased substantially in the past

few decades, at a pace that somewhat over our 10%-per-40-years criterion for

slowness. Elite journal authorship data support both 4a and 4b: Despite an

increase since the 1950s, rates of authorship appear to have flattened in the

low teens since the 1970s. Rates of extended discussion have likewise risen,

but slowly at best in ethics. Also supporting hypothesis 4a is the somewhat

younger mean birth year of women than men among authors most cited in the SEP.

Perhaps the clearest evidence for both 4a and 4b is the data from the Survey of

Earned Doctorates: The best-fitting quadratic curve shows a substantial

increase of the percentage of philosophy PhD’s awarded to women, from 17% in

the 1970s to 22% 1980s, but then flattening out around 27-28% from the 1990s to

the present.

We leave speculation

on causes and possible remedies to others. However we emphasize three features

of our findings that might be especially relevant to policy:

A. Journal editors

and conference organizers in ethics should not assume that a proportion of

women consistent with the proportion in philosophy as a whole (say, in the low

20%’s) is representative of the proportion of

available philosophers in ethics.

B. Although the

gender disparity in philosophy is large, it is even larger outside of ethics

than it is in ethics. Non-ethics fields might be in even more need of

intervention than would appear to be the case looking at the numbers in

philosophy as whole.

C. If it is true that

the 20th-century trend toward less gender disparity has slowed or stopped, then

current practices to encourage gender parity might not be enough to ensure

further progress toward that aim, and more assertive action might be required.[20]

References:

Alcoff, Linda

(2011). A call for

climate change. APA Newsletter on Feminism and Philosophy

11 (1): 7-9.

Australian Government, Department of Education and

Training (2015). Table

2.6 Number of Full-time and Fractional Full-time Staff by State, Higher

Education Institution, Current Duties and Gender, 2014. Selected Higher Education Statistics-2014

Staff Data, 2014 Staff Numbers

Beebee, Helen, and Jenny Saul (2011). Women in philosophy in the UK. British Philosophical Association: Society

for Women in Philosophy in the UK.

Bradley, Ben (2005). Ethics journals. Blog post at PEA Soup (Oct. 4) [reporting a survey results originally by Brian Weatherson]. URL:

http://peasoup.typepad.com/peasoup/2005/10/ethics_journals.html

Cameron, Elissa

Z., Angela M. White, and Meeghan E. Gray (2016). Solving the productivity and impact puzzle:

Do men outperform women or are metrics biased?

BioScience

advance: http://m.bioscience.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2016/01/05/biosci.biv173.full.pdf

Cohen, Philip N. (2011). Gender segregated sociology. Blogpost at Family Inequality (Jun. 10). URL:

https://familyinequality.wordpress.com/2011/06/10/gender-segregated-sociology/

Goddard, Eliza (2008). Improving

the participation of women in the philosophy profession. Australasian Association of Philosophy:

Committee of Senior Academics Addressing the Status of Women in the Philosophy

Profession. Available at:

http://www.aap.org.au/Resources/Documents/publications/IPWPP/IPWPP_ReportA_Staff.pdf

Grove, Jack (2013). Global gender index, 2013. Times

Higher Education. Feature article

May 2. URL:

https://www.timeshighereducation.com/features/global-gender-index-2013/2003517.article

Haslanger, Sally (2008). Changing the ideology and culture of

philosophy: Not by reason (alone). Hypatia 23:

210-223.

Healy, Kieran (2013). Lewis and the women.

Blog post June 19, updated Jun 26: http://kieranhealy.org/blog/archives/2013/06/19/lewis-and-the-women/

Hirshfield, Laura E. (2010).

“She won’t make me feel dumb”: Identity threat in a male-dominated

discipline. International Journal of Gender, Science,

and Technology 2 (1).

Available at: http://genderandset.open.ac.uk/index.php/genderandset/article/view/60

Larivière Vincent, Chaoqun Ni, Yves Gingras, Blaise Cronin, and

Cassidy R. Sugimoto (2013). Global gender disparities in science. Nature

504: 211-213.

Leiter, Brian (2009). Which

journals publish the best work in moral and political philosophy? Blog post at Leiter Reports

(Mar. 15). URL:

http://leiterreports.typepad.com/blog/2009/03/which-journals-publish-the-best-work-in-moral-and-political-philosophy.html Poll

results at: http://www.cs.cornell.edu/w8/~andru/cgi-perl/civs/results.pl?id=E_c5f31eca64119ba9

Leiter, Brian (2013). Top philosophy journals without regard to

area. Blog post at Leiter Reports (Jul. 6). URL:

http://leiterreports.typepad.com/blog/2013/07/top-philosophy-journals-without-regard-to-area.html

Leiter, Brian (2014). Departments ranked by SEP citations. Blog post at Leiter Reports (Aug. 14). URL:

http://leiterreports.typepad.com/blog/2014/08/departments-ranked-by-sep-citations.html

Leiter, Brian (2015a). Most important Anglophone philosophers,

1945-2000: The top 20. Blog post at Leiter Reports

(Jan. 29). URL:

http://leiterreports.typepad.com/blog/2015/01/most-important-anglophone-philosophers-1945-2000-the-top-20.html

Leiter, Brain (2015b). The top 20 “general”

philosophy journals, 2015. Blog post at Leiter Reports

(Sep. 28). URL:

http://leiterreports.typepad.com/blog/2015/09/the-top-20-general-philosophy-journals-2015.html

Morley, Louise, and Barbara Crossouard (2014).

Women in higher education leadership in South Asia: Rejection, refusal,

reluctance, revisioning. University of Sussex: Centre for Higher

Education & Equity Research.

Available at:

https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/morley_crossouard_final_report_22_dec2014.pdf

National Center for Education Statistics

(2015). Table 315.20. Available at:

http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d14/tables/dt14_315.20.asp

Norlock, Kathryn J. (2006/2011). Women

in the profession: A more formal report to the CSW. Updated 2011. Available at:

http://www.apaonlinecsw.org/data-on-women-in-philosophy

Paxton, Molly, Carrie Figdor, and Valerie

Tiberius (2012). Quantifying the gender

gap: An empirical study of the underrepresentation of women in philosophy. Hypatia 27:

949-957.

Pion, Georgine M., Martha T. Mednick, et al.

(1996). The shifting gender composition

of psychology: Trends and implications for the discipline. American

Psychologist 51: 509-528.

Schwitzgebel, Eric (2010). Discussion arcs. Blog post at The Splintered Mind (Apr. 27). URL:

http://schwitzsplinters.blogspot.com/2010/04/discussion-arcs.html

Schwitzgebel, Eric (2012). Women’s roles in APA

meetings. Blog

post at The Splintered Mind (Mar. 15).

URL:

http://schwitzsplinters.blogspot.com/2012/03/womens-roles-in-apa-meetings.html

Schwitzgebel, Eric (2014a). Citation of women and

minorities in the Stanford Encyclopedia

of Philosophy. Blog post at The Splintered

Mind (Aug. 7). URL:

http://schwitzsplinters.blogspot.com/2014/08/citation-of-women-and-ethnic-minorities.html

Schwitzgebel, Eric (2014b). The 267 most-cited authors

in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Blog post at The Splintered Mind: Underblog (Aug. 7).

URL:

http://schwitzsplintersunderblog.blogspot.com/2014/08/the-266-most-cited-contemporary-authors.html

Schwitzgebel, Eric (2015). Percentages of women on the

program at the Pacific APA. Blogpost at The Splintered Mind

(Mar. 31). URL:

http://schwitzsplinters.blogspot.com/2015/03/proportions-of-women-on-program-of.html