Chapter Eight

When Your Eyes Are Closed, What Do You See?

What they were asked to do was briefly this: to close the eyes, allow the after-images completely to die away, and then persistently and attentively to will that the color-mass caused by the Eigenlicht should take some particular form, – a cross being the most experimented with.

– George Ladd, “Direct Control of the Retinal Field” (1894, p. 351, italics in original)

i.

I’d prefer to end this book with a sprouting tangle of questions than with the pessimism of the previous chapter. I’m not an utter skeptic; nor do I think we should abandon efforts to understand the stream of experience. Let’s plunge once more into the thicket, with a fresh topic.

ii.

The first scholar I’m aware of to seriously consider what we see when our eyes are closed was the eminent early 19th century physiologist – the first great introspective physiologist – Johann Purkinje (a.k.a. Jan Purkyne, 1787-1868), in his doctoral dissertation Contributions to the Knowledge of Vision in Its Subjective Aspect (1819/2001), a work groundbreaking in its attention to phenomenological detail.[1]

Purkinje begins his dissertation with a phenomenon he discovered in a childhood game:

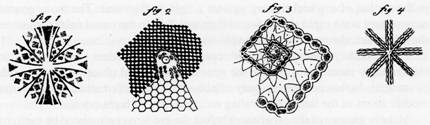

I stand in bright sunlight with closed eyes and face the sun. Then I move my outstretched, somewhat separated, fingers up and down in front of the eyes, so that they are alternately illuminated and shaded. In addition to the uniform yellow-red that one expects with closed eyes, there appear beautiful regular figures that are initially difficult to define but slowly become clearer. When we continue to move the fingers, the figure becomes more complex and fills the whole visual field (figs. 1-4 [fig. 8.1]).

Fig. 8.1, “light and shade figures”, from Purkinje 1819/2001, p. 69

This is what happens in general. Now to the single instances and to closer definition of the conditions. I will first consider the observations of the figures in my right eye, and will mention those for the left eye later.

In general, I differentiate primary and secondary forms in the whole figure. The primary patterns define the background while the secondary are superimposed on it. The primary forms are larger and smaller squares (fig. 2) alternately light and dark, which cover most of the field, resembling a chess board.

At the borders of the squares longer and shorter zigzag lines develop that appear here and there and then vanish. Outward from the center, which is marked by a dark point surrounded by a light area, I see a field of larger hexagons, with gray sides and white centers. To the lower left of the central spot I see overlapping half circles, the direction of which continuously changes. They resemble tree rings or roses with many petals.... [Purkinje’s descriptions continue for another page and a half.]

Further I must stress that the patterns I have described, especially the squares, have been seen by the majority of people with whom I have carried out the experiment, in so far as they can be communicated by verbal reports not accompanied by drawings....

The patterns in my left eye, which is weak sighted, can only be seen incompletely. The primary patterns appear as curvilinear networks rather than as regular squares. The secondary patterns, however, are the same, only they are placed at opposite sides (1819/2001, p. 69-71).

Several other authors attest to such phenomena: Helmholtz says that such figures emerge in conditions of a “rapid change of light and shadow” (1866/1909/1962, vol. 2, p. 257). J.R. Smythies (1957) and Steven Stwertka (1993) call them “stroboscopic patterns” and find that they can be induced by a strobe light flashing about 10 times per second. G.B. Ermentrout and J.D. Cowan (1979) provide a mathematical explanation of why such geometrical figures might appear in hallucinations. I’ve so far been unable to find such geometric organization in my own case – neither using Purkinje’s splayed fingers technique, nor with a stroboscope. In both cases, I seem to experience an unsteady, quickly flashing, light and dark, noisy background and small colored figures that come and go.

In this passage, Purkinje comments only briefly on non-stroboscopic experience while facing the sun with one’s eyes closed – that “one expects” a “uniform yellow red”. Elsewhere in his dissertation, and in a 1825 follow-up volume, Purkinje discusses various striking subjective visual phenomena, some occurring with eyes closed, others with eyes open. Among the eyes-closed experiences he discusses are: the “cross-spiderweb” figures he sees when he suddenly wakes up with the sun shining on his closed eyes (1825/1919, §VIII), the “wandering cloudy stripes” he sees with eyes closed in darkness (see section iv below), the various “pressure figures” induced by pressing on his eyes (1819/2001, §II-III), the “galvanic light figures” produced by running electric current through his face (1819/2001, §IV), the squares he sees when he restricts the blood flow to his head (1819/2001, §III), and the ellipse he sees when, after closing his eyes and attending to things non-visual for a while, he with a sudden jerk of the eyes attends to his darkened visual field (1825/1919, §V). But experience in ordinary daylight with his eyes closed seems never to have attracted Purkinje’s attention. Perhaps the casual remark in the passage above reflects his final opinion: It’s a simple yellow-red, hardly worth further discussion.

iii.

Like Purkinje, later authors almost entirely ignore the question of what we normally experience with our eyes closed in well-lit environments. I can find no serious treatments.[2] But can’t we, if we want, just go out, lie in the sun, and see? (How’s the weather?) Will we then be doing science?

Here’s what I’m inclined to report: a bright, relatively uniform field that fluctuates in color from warm hues like red and orange and brilliant scarlet, to white or dull gray, sometimes with a faint bluish tinge. The changes of hue are sometimes seemingly spontaneous, at other times precipitated by moving my eyes or tightening my lids. The field seems to churn throughout with a darker color, and I see flashes of brightness at the extreme periphery. The field seems broader than it is high, and either flat and a few inches before me or – alternatively and quite differently – entirely lacking any features of distance or depth or flatness.

I coaxed two friends into reporting their visual experience while facing the sun for seven minutes with their eyes closed. Both described experiences similar to mine: bright fields fluctuating in color from red to orange or yellow or white. Both described the field as fairly uniform, though with some perturbations (one reported diagonal lines that came and went, the other reported squiggles and lightning-like branching figures). When I asked about the periphery, both described it as similar to the center, though possibly a bit darker. Incidentally, both friends’ pupils contracted over the course of the experiment, suggesting that appreciably more light penetrates the closed eyelid when facing the sun than enters the open eye in normal indoor environments.

I also loaned random beepers (of the sort used in Chapter 6) to five experimental subjects, asking them to report on their visual experience with their eyes closed in a variety of circumstances. More on that later.

You might think: Who cares what we visually experience when the sun shines through our eyelids? Well, here are two possibilities: Everyone reports pretty much the same thing, in which case there is probably no reason to doubt the reports, and simply by lying on our backs in the sun we’ve discovered something new, and at least a little bit cool, despite having almost two centuries of consciousness studies behind us. Or people disagree, and we have the same wonderful, horrid mess on our hands that erupts in every other chapter of this damn book.

iv.

Less apparently useless or maybe more intrinsically interesting – in any case much more discussed – is what we experience when the eye is virtually or entirely darkened, for example when one sits with eyes closed in an unlit room at night. Purkinje calls this the “dark field”.

Wandering Cloudy

Stripes

When I fixate the darkness of an eye, well protected from all external light, sooner or later weakly emerging fine, hazy patterns begin to move. At first they are unsteady and shapeless, later they assume more definite shapes. The common feature is that they generate broad, more or less curved bands, with interpolated black intervals. These either move as concentric circles toward the center of the visual field, and disappear there, or break down and fracture as variable curvatures, or as curved radii circle around it (figs. 17-19 [fig. 8.2]). Their movement is slow, so that I usually need 8 seconds until such a band completes the journey and disappears completely. Even at the beginning of the observation the darkness is never complete. There is always some weak, chaotic light. It is strange that in this darkness the sense of proportions fails completely. The darkness is finite, extended in width. It is possible to measure it from the center, but one cannot determine precisely the peripheral limit. The closer we come to the periphery, the more difficult and finally impossible it gets to establish a visible peripheral limit....

The figures described were seen with my right eye, because the left eye, which is somewhat weak, would not notice these delicate phenomena. In individuals in whom the two eyes are identical, probably the figures would unite just as the two fields of vision fuse into one (1819/2001, p. 79-80).

Fig. 8.2, “wandering cloudy stripes”, from Purkinje 1819/2001, p. 80

In his 1825 volume Purkinje adds:

In most cases after some minutes the... wandering cloudy stripes begin their game, often developing such vivacity that they give themselves colored appearances. Later a profusion of straight and crooked lines of different lengths appear, the straight frequently standing parallel and vertical, the crooked irregular and fragmentary. Sometimes a checkerboard appears or fragments of an eight-ray star.... The slightest involuntary movements bring out the always delicate emerging sensitivity of the various light phenomena of appearance, even more toward the outer part of the visual field than in the middle (1825/1919, p. 105-106, my trans.).

Johann Goethe (whom Purkinje credits in his 1825 book but not his 1819) somewhat anticipated Purkinje’s wandering cloudy stripes, writing:

If the eye is pressed only in a slight degree from the inner corner, darker or lighter circles appear. At night, even without pressure, we can sometimes perceive a succession of such circles emerging from, or spreading over, each other (1810/1840/1967, §96).

Let’s follow these wandering cloudy stripes down through the 19th century, as they change and disappear.

v.

The next discussion I can find of the dark field is by the 19th century’s next great introspective physiologist, Johannes Müller (1801-1858), some twelve years later:

If we direct our attention to what takes place in the eyes when closed, not merely do we see sometimes a certain degree of illumination of the field of vision, but also occasionally an appearance of light developed in greater intensity; sometimes, indeed, this luminous appearance spreads from the centre to the circumference, in the form of circular waves, disappearing at the periphery. At other times the appearance has more the form of luminous clouds, nebulæ or spots; and, on rare occasions, it has been repeated in me with a regular rhythm (1837/1843, p. 742).

Though in some ways strikingly similar to Purkinje’s description – and Müller mentions Purkinje four times on this page, but oddly not on this issue – Müller’s description is more limited, mentioning only circular waves and not the other forms Purkinje reports. He also describes them as moving in the opposite direction: not toward the center but rather outward toward the periphery.

Nineteen years after Müller’s discussion, Helmholtz appears to be of two minds, first characterizing the dark field quite differently:

When the eyes are closed, and the dark field is attentively examined, often at first after-images of external objects that were previously visible will still be perceived.... This effect if soon superseded by an irregular feebly illuminated field with numerous fluctuating spots of light, often similar in appearance to the small branches of the blood-vessels or to scattered stems of moss and leaves, which may be transformed into fantastic figures, as is reported by many observers (1856/1909/1962, vol. 2, p. 12).

But then he adds that many people, including Goethe and Purkinje, report wandering cloudy stripes. Helmholtz continues:

The author’s experience is that [wandering cloudy stripes] generally look like two sets of circular waves gradually blending together towards their centre from both sides of the point of fixation. The position of this centre for each eye seems to correspond to the place of entrance of the optic nerve; and the movement is synchronous with the respiratory movements. One of Purkinje’s eyes being weaker than the other, he could not see those floating clouds except in his right eye. The background of the visual field on which these phenomena are projected is never entirely black; and alternate fluctuations of bright and dark are visible there, frequently occurring in rhythm with the movements of respiration... (p. 12-13).

In describing two sets of circular waves, Helmholtz departs from both Purkinje and Müller (though with a nod to Purkinje’s weak eye). Helmholtz calls such visual experiences without outside light the eigenlicht or the “intrinsic light” of the eye.

Nine years later, Hermann Aubert, adopting a phrase from Purkinje, calls our visual experience in darkness light chaos. Although no previous author claims that cloudy stripes are the only stable inhabitants of the dark field, in Aubert they jostle against multiple competitors. Aubert describes the light chaos as “a swarm of spots, lines, and splotches of light, difficult to describe, spread over the entire visual field” and specifies five forms: (1.) black, but not deepest black, with yellow spots and lines of light like “hovering threads of fiber”, (2.) colorless wandering cloudy stripes in Purkinje’s sense, moving in all directions, (3.) fogballs in the middle of the visual field, expanding and contracting without much other movement, brighter in the center and fading toward the edges without a distinct boundary, (4.) very bright lights at the far periphery, usually disappearing quickly, and (5.) zigzag lines, like bright lightning, blue or violet in color, moving slowly and disappearing within a few seconds (p. 333-334, my trans.). Aubert estimates the brightness of the black background as similar to that of a sheet of white paper illuminated by a single candle 130 meters away (p. 64).

Despite their impressive pedigree in Goethe, Purkinje, Müller, and to some extent Helmholtz – and who could ask for more expert witness in the early 19th century? – after Aubert, the wandering cloudy stripes seem to dissipate. The next serious discussion of them is in an 1897 journal article by Edward Scripture. Scripture rejects Helmholtz’s claim that people see one figure for each eye, and he describes the stripe as a “spreading violet circle”. After Scripture, I can find no psychologist who treats wandering foggy stripes as the characteristic inhabitants of the dark field.

vi.

Meanwhile, another tradition – or, really, set of conflicting traditions – was arising, which did not venture to predict any particular pattern in the visual field of the light-deprived eye.

Gustav Fechner offers the first serious treatment of eyes closed visual experience with no reference to Purkinje’s cloudy stripes. His label for the experience, augenschwarz, literally eye-black, emphasizes its darkness. He writes:

The blackness that is present when the eyes are closed is rather just the same impression of light as we get when viewing a black surface, one which can change through all gradations to the most intense visual sensation. Indeed, this intrinsic blackness of the eye changes occasionally through purely internal causes into bright light and contains, so to speak, a sprinkling of light phenomena.

By paying strict attention, one discovers in the blackness that is seen when the eyes are closed a kind of fine dust composed of light, which is present in different people and under different conditions of the eye in various states of abundance, and in certain diseases may increase to a lively phenomenon of light. In my own eyes there exists, since the time when I had a lengthy disease of the eye, a strong continuing flickering of light, which increases according to the stimulation of my eyes and is subject to great fluctuations (1860/1964, p. 138).

Fechner doesn’t cite Purkinje, Müller, or Helmholtz here. Though his brief discussion on p. 136-138 doesn’t preclude the possibility that wandering cloudy stripes may be among the “sprinkling of light phenomena”, they rate no mention. Throughout his Elements of Psychophysics, especially in the second volume, Fechner treats the augenschwarz as near the lowest bound of blackness; and he discusses the self-reports of several correspondents who describe their visual field with their eyes closed as either purely black or very nearly so (1864/1889, p. 478-483).

While Fechner evidently regards the regular experience of bright light in the augenschwarz as a sign of pathology, American psychologist George Ladd suggests that it is only amateurish introspection that leads to reports of the field as mostly dark:

I have found by inquiry that a large proportion of persons unaccustomed to observe themselves for purposes of scientific discovery are entirely unacquainted with the phenomena of the retinal eigenlicht. Ask them what they customarily see when their eyes are closed in a dark room and they will reply that they see nothing. Ask them to observe more carefully and describe what they see, and they will probably speak of a black mass or wall before their eyes, with a great multitude of yellow spots dancing about on its surface. Some few will finally come to a recognition of the experience with which I have long been familiar in my own case. By far the purest, most brilliant, and most beautiful colours I have ever seen, and the most astonishing artistic combinations of such colours, have appeared with closed eyes in a dark room. I have never been subject to waking visual hallucinations, but I verily believe there is no shape known to me by perception or by fancy, whether of things on the earth or above the earth or in the waters, that has not been schematically represented by the changing retina images under the influence of intra-organic stimulation (1892, p. 300; see also Galton 1883/1907[3]).

Still differently, Ewald Hering calls the phenomenon eigengrau, “intrinsic gray” (1905, 1920/1964; in 1878 he was still using Helmholtz’s eigenlicht). His choice of gray over Fechner’s black is deliberate: In the absence of contrast, especially after a long time, Hering suggests, we experience not so much darkness as neutral gray:

If we awake at

night when it is still completely dark, at first we distinguish no objects at

all, but see the whole visual field filled merely by those weak, more or less

unsteady, cloudy or spotty colors which one can call the intrinsic gray (intrinsic brightness or darkness) (1920/1964, p.

74-75).

That the field should be gray and not black fits nicely with Hering’s emphasis on opponent processes in vision, according to which visual sensation involves competition between light and dark, red and green, blue and yellow, all arising in contrast to a neutral resting state, toward which one starts to gravitate with adaptation. On such a view it’s natural to suppose that with persistent non-stimulation, one would revert to a neutral sensation, not a dark one (see also G.E. Müller 1896, p. 30-33, 1897, p. 40-46). Why, then, might people misreport the experience? Hering suggests that the gray or weak colors we experience when the eye is not stimulated, like afterimages and peripherally seen objects, have less “weight” (gewicht), that is, “the impressiveness or expressiveness that a visual quality or color possesses” which causes us to notice and remember it (p. 115-116). This is not at all the same as their being dark, but perhaps the casual introspector would confuse the two. Or – though I recall no hints of this in Hering – perhaps it’s an instance of “stimulus error” (see Chapter 6 and Boring 1921) – the mistake of confusing the features of the outside world (that it’s dark, or that no appreciable light is entering the eyes) with the features of the sensory experience the outside world produces in us.

Other psychologists offer passing comments. Alfred Volkmann describes the field as absolute blackness but with a “light dust” that varies between people (1846, p. 311). Adolf Fick describes the field as “constantly changing, with all kinds of turbulence, in places colored, in places colorless marks, with shape and color steadily changing” (1879, p. 230, my translation). Edmund Sanford invites students to consider the “shifting clouds of [idio-retinal] light” in the darkened eye (1892, p. 485, brackets in original). G.F. Stout describes “the retina’s own light” as “medium gray” with “specks and clouds of color” (1899/1977, p. 151). Titchener describes “hazy or cloud-like patches of dull grey” (1901a, vol. 1, p. 510) and says “we see a grey, ... an ‘intrinsic’ brightness sensation” 1901b, p. 79). “Mr. H.D.” (with an 1896 Yale Ph.D.) says that his eigenlicht ordinarily has “the appearance of a dancing mass of vari-colored dust, red predominating” and that it’s normally circular, centered at the bridge of the nose, while “the radius extends to the corner of the eye and sweeps over the forehead to the other eye” (quoted in Ladd 1903, p. 145). Wundt describes “weak subjective light sensations” in the form of “light nebulas and light sparks” (1908, p. 660, my trans.). William Peddie describes the “self-light” as an “irregularly flecked shimmer” of yellowish-white (1922, p. 44, 84). Leonard Troland says that the visual field is “relatively homogeneous and lacking in stereoscopic character”, and “faint patterns of colors... idio-retinal whirlings and the like, may be present” (1922/2008, p. 16). Frank Allen says we experience a “misty dark gray light” (1924, p. 275). Burch writes that with “prolonged resting of the eye in an absolutely dark room, the self light slowly diminishes and finally disappears” (quoted in Allen 1924), while Boring remarks in contrast that “the black of complete darkness gets subjectively lighter as it continues (1942, p. 163). Karol Koninski says “the visual field appears as regular bluish-(ink-)black grains (the grains millet- to lentil-sized) on a yellow background (1934, p. 362, my trans.). Donald Purdy describes the “self light” as “a uniform dim expanse of gray” (1939, p. 531). Phenomenological reporting went out of style in psychology and thoughtful descriptions of the eigenlicht become harder to find after the 1930s (though see this note[4] for some later quotes, and this note[5] for a few words on “sensory deprivation” and “ganzfeld” experiments).

Could all these men just be having different experiences, which they are each accurately reporting? Maybe Hering genuinely experienced gray, Fechner black, Ladd fantastic colors, Purkinje a parade of cloudy stripes converging inward, and Scripture a crimson band spreading outwards. When deprived of stimuli and free to play, our brains might fall into different habits. And yet Ladd is convinced that people who manage to introspect carefully will come to agree with him. Surely this must have been his experience in conversation, at least with his students? Most researchers represent their experiences not as idiosyncratic but as typical. One would hope that they’d base such claims partly in reports gathered from others; and Fechner, at least, does so explicitly. It would be strange if all of Fechner’s acquaintances happened to see black and all of Hering’s gray. There’s also an odd historical arc to the reports of wandering cloudy stripes, which reminds me of the arcs of opinion about black and white dreams (Chapter 1) and the elliptical appearance of tilted coins (Chapter 2).

Maybe people experience more or less what they expect to experience? That could explain the historical arcs and the similarity among researchers’ students and acquaintances. Against this, though, at least some people say they are surprised at what they discover, for example Galton (see the quote in note 3), as well as many of the acquaintances and subjects I’ve interviewed.

vii.

We might turn to neuroscience. Neurons are always active, even in the absence of stimulation. For example, Tal Kenet et al. (2003), looking at cats, found that “spontaneous activity” (in the dark or looking at a gray screen) in area 18 (associated with selectivity for the orientation of visual stimuli) often closely resembled, with somewhat less organization, ordinary area 18 activity in response to visually presented gratings. But there is no straightforward inference from neural firing patterns to phenomenology, at least in the current state of neuroscience, and phenomenological studies are lacking: Despite the fact that subjects often lie in the dark in MRI machines, neuroscientists interested in vision understandably tend to focus on what occurs not in the darkness but rather when visual stimuli are presented.

One exception is Yuval Nir et al. (2006), who asked subjects to describe any “visual-like perceptions that might occur” during two minutes of complete darkness with eyes closed inside an MRI machine. Five of the seven subjects reported no visual-like percepts whatsoever; one reported afterimages in the first few seconds, nothing otherwise; and the last reported “visual-like” dots. Although there’s something to be said for brevity and neutrality in one’s introspective instructions, I worry about that Nir and colleagues are too casual here. What does it mean for a subject to report “nothing”? Does that mean blackness, or no visual experience at all (like the lack of visual experience of things behind your head; see the “phenomenal blindness” thought experiment in Chapter 6), or nothing that seems important, or nothing that the subject would confuse with a sensation caused by an ordinary outward object? The experimenter who has theoretical conversations with her subjects invites the charge of imposing her own views and thus polluting the reports. Rightly so. But sometimes, as here, without such conversations, the reports are uninterpretable, creating a methodological Scylla and Charybdis. (And no, Odysseus did not steer between them. He chose Scylla and paid the price.) Anyhow, Nir et al. found considerable fluctuation in visual cortical activity among their subjects, despite the subjects’ minimal reports.

I see no reason neuroscientific studies couldn’t cast some light. However, as far as I’m aware nothing even close to methodologically adequate has yet been attempted.

viii.

I close my eyes right now and consider my visual experience. I feel little room for doubt. The field is mainly black, with hints or tintings of color. After contemplating it for ten seconds, I place my palms gently over my eyes. Ah wait, I think, now it’s black! I remove my palms and the field now seems like an intermediate gray – and that seems to me now to be the color it was before, originally, when I thought it was black. Was that first assessment, which seemed so easy, actually mistaken? Or am I losing track of how my experience has evolved over even these brief periods of time? Does my concept of blackness or darkness apply well only to the outside world, or to my experiences of the outside world, so that it’s always something of a distortion to apply it to my experience with my eyes closed? Why does even so apparently easy an introspection confound me?

Helmholtz writes:

Another general characteristic property of our sense-perceptions is, that we are not in the habit of observing our sensations accurately, except as they are useful in enabling us to recognize external objects. On the contrary, we are wont to disregard all those parts of the sensations that are of no importance so far as external objects are concerned [emphasis in original]. Thus in most cases some special assistance and training are needed in order to observe these latter subjective sensations. It might seem that nothing could be easier than to be conscious of one’s own sensations; and yet experience shows that for the discovery of subjective sensations some special talent is needed, such as Purkinje manifested in the highest degree; or else it is the result of accident or of theoretical speculation. For instance, the phenomena of the blind spot [where the optic nerve exits the eye] were discovered by Mariotte from theoretical considerations. Similarly, in the domain of hearing, I discovered the existence of those combination tones which I have called summation tones [see Chapter 5, §iv].... It is only when subjective phenomena are so prominent as to interfere with the perception of things, that they attract everybody’s attention.... Even the after-images of bright objects are not perceived by most persons at first except under particularly favorable external conditions.... No doubt, also, there are cases where one eye has gradually become blind, and yet the patient has continued to go about for an indefinite time without noticing it, until he happened one day to close the good eye without closing the other, and so noticed the blindness of that eye (1856/1909/1962, vol. 3, p. 6-7).

Immediately following this passage is Helmholtz’s assertion, quoted in Chapter 2, §vii, that people are typically astonished to discover that most of the objects in their visual field, most of the time, are seen double. Later on the same page, Helmholtz lists “the ‘luminous dust’ of the dark field” among the subjective phenomena so difficult to heed.

Here, as in my discussion of the subjective “flight of colors” after exposure to bright light (Chapter 5, §v), I find myself torn between on the one side a subjective feeling of confidence, a sense that I couldn’t really go too far wrong, a sense that I can doubt only inauthentically, as dogmatic skeptics are prone to do, and, on the other side, the concern that my, or our, subjective confidence may be poorly tuned in this domain, as suggested by Helmholtz and Ladd – men who have studied the phenomena more carefully than I, with (presumably) more subjects than I, and who insist that it is remarkably easy for untutored introspection to go astray.

ix.

One thing that everyone in this literature appears to agree on is that we normally have some visual experience or other when our eyes are closed – at least, they all seem naturally to invite that reading, and they don’t ward against it. Recall, however, the sparse view of consciousness from Chapter 6. On the sparse view, we don’t normally experience, even peripherally, the unattended hum of traffic in the background, the pressure of the shoes on our feet, or even the road before our eyes when we’re driving inattentively. If it seems to us that we constantly experience everything simultaneously, that’s only because the act of attending creates the experience in question. And if ever we should lack visual consciousness, it seems it should be when our eyes are closed – unless, of course, for some reason we happen to be thinking specifically about our eyes-closed visual experience. On this view, we don’t so much discover the eigenlicht when we think about it, but bring it into being.

Borrowing the methodology of Chapter 6, I loaned random beepers to five volunteers, who wore them for two hours at a stretch, keeping their eyes closed the whole time. When the beep sounded, they were to consider whether they had any sort of visual experience – blackness, colors, fantastic figures, whatever – in the last undisturbed moment before the beep, or whether they had no visual experience whatsoever, not even of blackness or grayness. If they did believe they had some experience, I asked them to describe it in as much detail as possible. I interviewed participants closely about their sampled experiences (or non-experiences); I encouraged open questioning of the methodology; I attempted to clarify as much as possible about what was being asked, while minimizing or hiding my own inclinations; and I aimed to elicit the participant’s best judgment about the matter at hand under the pressure of frank but gentle expression of sources of concern.

I made as clear as I could the difference between no visual experience and the experience of black or gray. One technique I used to convey the idea was this: First I asked participants if it seemed to them that they experienced blackness or grayness or anything else visual in the region behind their heads and beyond the farthest boundary of their peripheral vision, or whether it seemed instead empty or blank – not black, but rather entirely devoid of visual experience. All expressed the view that beyond the periphery it was visually blank, not black. I then asked them to imagine the blankness encroaching, the periphery narrowing, until no visual experience whatsoever remained but only blankness. The question then is: Is that what it’s like when your eyes are closed and you’re caught up in thinking about something else, or is it more like seeing black, or gray, or colors, or figures?

I also distinguished sensory visual experience from visual imagery experience. Visually imagine a setting sun in a cloudy sky. If you can do this, you presumably had a visual imagery experience that was somewhat different in kind – or at least in vividness (Hume 1740/1978; Perky 1910) – from your sensory visual experience ongoing now. People don’t seem usually to have trouble distinguishing imagery experience from sensory experience when their eyes are open, but when their eyes are closed, people sometimes seem to lose hold of the distinction. I invited participants to consider whether that distinction made sense to them, and if so to report whether any visual experience they had seemed more sensory or more imagistic. All participants accepted the distinction and confidently classified each of their visual experiences in one or the other category. In some cases, they reported both sensory and imagery experience. Always, in such cases, the two were experienced as distinct from each other – for example, a sensory experience of a uniform, bright orange field and simultaneously a visual image of the Google guys dressed in black.

Table 8.1 displays the results, by subject, collected over three (or for subject 1, four) separate beep and interview days. My sense of the subject’s “bias” was based on what the subject said in the preliminary interview. Only S2 ever reported thinking about the experiment or about his ongoing visual experience in the moment immediately before the beep. Unfortunately, he reported this in 6 of his 10 samples. All other participants were quickly swept up in radio programs, telephone conversations, and the like. As is evident from the table, the variation between respondents was extreme: One subject (S2) reported sensory visual experience in every single sample, while another (S4) never reported visual experience of any sort.

TABLE 8.1: Reported visual sensory and visual imagery experience in randomly sampled moments, with eyes closed

|

subject |

bias |

sensory only |

imagery only |

both |

neither |

|

S1 |

thin |

1 (7%) |

8 (57%) |

3 (21%) |

2 (14%) |

|

S2 |

rich |

9 (90%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (10%) |

0 (0%) |

|

S3 |

thin |

9 (75%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

3 (25%) |

|

S4 |

thin |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

9 (100%) |

|

S5 |

rich? |

8 (80%) |

1 (10%) |

1 (10%) |

0 (0%) |

|

total |

|

27 (49%) |

9 (16%) |

5 (9%) |

14 (25%) |

Four of my beeper subjects had their eyes closed in near darkness. One (S1) reported no sensory visual experience at all, not even of blackness, in six separate samples. Another (S2) reported, in two samples, an “undulating blackness” with small flashes of color. Another (S3) reported turbulent blackness on one occasion, like water before a boil, but no visual experience at all on a second occasion. A fourth (S5) reported grayish, angular wisps of foggy light against a black background in one sample and no sensory visual experience (but a vivid visual image) in another.

S2 collected four samples outside, facing the sun. In each sample, he described complex latticeworks, like a “squashed Bucky-ball”; in two he also reported a glowing light in the center (though not quite in the direction of the sun and too large to be a direct perception or afterimage of the sun). When I showed him Purkinje’s “light and dark figures” (see §ii, fig. 8.1), he said that his experience was similar. S5 collected two samples facing the sun. He reported neither S5’s latticework nor my own relatively uniform field fluctuating from red or yellow to white or gray (§iii). In one sample, he described the field as a dark orange oval becoming bright white near the center, with a horizontal orange band dividing it across the middle, and bright, iridescent spots throughout, fading in and out. In the other sample he reported a bright yellowish-white field riddled with whitish-blue vertical stripes and spots, accented with flecks of orange.

We might take the reports at face value, as indicating substantial variability in people’s experiences with their eyes closed. Or we might doubt the truth of the reports. The same issues arise as I noted Chapter 6, §x; no need to repeat them here. Also, the experimental situation – in which participants’ eyes were closed for long stretches, despite their being awake and active – differs, perhaps importantly, from the more typical situation of closing one’s eyes to fall asleep or closing them wakefully but only briefly. In the beeper experiment detailed in Chapter 6, two subjects did by chance have their eyes closed at the moment of the beep. One was closing her eyes in frustration; the other had fallen asleep. Neither reported any visual experience.

x.

Can you see through your eyelids?

If I’m in an illuminated room and I wave my hand before my face, I seem to experience motion of some sort – fluctuations in the visual field timed to match the motions of my hand. If I move my hand slowly from left to right and back again, taking about a half a second per sweep, I can seemingly track the position of my hand, though I can’t make out any hand shape. But maybe since I know where my hand is, I only seem to see it – maybe I’ve tricked myself, as does the spelunker who waves her hand in front of her face and reports seeing it despite utter darkness. (The spelunker will never see her friend’s hand.)

I cover my eyes with a book and wave my hand behind the book. Do I experience the motion? Not nearly as vividly, if at all. If a friend waves her hand before my face, I can sometimes track it, especially if the lighting is arranged so that the shadow of her hand crosses my eyes; but definitely not if there’s an intervening book. Friends, acquaintances, and loitering undergraduates, I’ve found, differ substantially in their reports and apparent skill at this task.

If I half cover my face with the book, the impression of movement returns vividly again – but oddly not just in the half of the visual field that, when I reopen my eyes, I would describe as unoccluded by the book. Rather the sense of motion seems to spread across the most of the field. This seems to be true whenever the angle of occlusion matches the angle of motion (e.g, book covering the lower half of visual field and my hand moving right and left; the book covering the left field and my hand moving up and down).

xi.

Purkinje distinguishes what he experiences in his right eye from what he experiences in his left. When I close my own eyes, I can easily distinguish between the right and the left halves of the darkness – yes, it still seems to me like mostly darkness – but I don’t find any impulse to ascribe different fields to my two eyes: The field seems to me (in the language of Helmholtz 1856/1909/1962 and Julesz 1971) cyclopean. This, despite the fact that, like Purkinje, one of my eyes is very much weaker than the other.

If I open my left eye, what happens to the darkness? My first temptation is to say that it disappears entirely. What a little more reflection, though, it starts to seem to me that there is a small margin of darkness, still – at least when I attend to it – on the far right of the visual field – but as though seen from the perspective of the left eye – as though the right side of my visual field is behind my nose. There is, I’m inclined to say, no visual experience, no visual perspective, phenomenologically associated with my right eye at all, not even darkness. But not everyone reports the same. One participant in the eyes-closed beeper study (S1) said (based on his introspection there in my office, not as part of a beeper-sampled experience) that it seemed to him, with one eye closed, as though his closed eye was seeing blackness and his open eye was seeing an ordinary visual scene. Do we experience these things differently, or is one of us mistaken?

Most people, if they press the corner of an eye, will report a figure, called a phosphene, in the opposite corner, often (it seems to me) a dark circle with a bright aura (see, again, Purkinje 1819/2001 and Helmholtz 1866/1909/1962). Sometimes I find it helps to make the phosphenic phenomenology more salient (or to bring it into existence?) if I wiggle my finger a bit. Now I close my eyes and press the outside corner of my left eye and note the phosphene. (There is also a colored smudge directly at the location of the pressure, which I don’t think I generally see when I press on my open eyes with the same force; but that’s not the phosphene I have in mind.) I find myself torn between saying that this phosphene appears about 2/3 of the way toward the right border of a cyclopean dark field and saying that it appears at the far edge of a field specifically associated with my left eye. Furthermore, it seems that to observe the phosphenes of my right eye, it helps if I to shift my energies to that eye, as it were, and observe the field that eye presents. So maybe the field is not as cyclopean as I first thought?

With one eye open, I can move my finger to push my phosphene behind my nose and deep into my face, noting where it finally disappears. If I then open the opposite eye, the point of disappearance marks the peripheral border of that eye’s vision.

xii.

Recall that Purkinje describes the visual field of his darkened right eye as “finite, extended in width. It is possible to measure it from the center, but one cannot determine precisely the peripheral limit. The closer we come to the periphery, the more difficult and finally impossible it gets to establish a visible peripheral limit” (1819/2001, p. 79-80). When I close my eyes, whether in darkness or light, this description seems apt to me: With eyes open, there’s a fairly straightforward (though indistinct) border to my visual field, but not with eyes closed. The darkness feels somehow more enveloping – though it also feels more to be in my forward than in my rear perspective. Does it actually extend over a greater degree of visual arc? Well, I’m not sure I’m ready to say that. When I’ve asked others, informally, the reports are diverse – some claiming a distinct border (see also H.D. quoted in §vi above), some denying such a border; some saying their field has the same angular extent as their eyes-open visual field, others saying it’s smaller; but none (among those I’ve spoken with so far) saying it seems to surround them a full 360 degrees.

Purkinje emphasizes the horizontal dimension, but the same question arises vertically. Eyes open, I’d say the visual field seems less tall than wide. Many of my observers, both formally and informally, have reported that the same is true of their eyes-closed visual field. Sometimes I’m inclined agree; H.D., however, describes the field as circular.

xiii.

Many descriptions of the eyes-closed visual field implicitly treat it as flat. This reminds me, of course, of the issues raised in Chapter 2. Purkinje’s checkerboard shapes, for example (§2, fig. 8.1), are drawn as though seen square-on, not receding into the distance at some angle. Likewise he does not portray his stripes as moving forward and back or twisting in three dimensions: They are spreading circles or arches or S’s, as though on a two-dimensional field. Although a number of authors (as well as most of my S1-S5) describe a “background” (often black or gray or in the sun more brightly colored) against which other figures move, this doesn’t necessarily imply any real depth to the field. None of my subjects ever reported its seeming as though one object in their eyes-closed field in some substantial sense looked farther away than another, though I explicitly asked each subject (except S4, who reported no experience) a few times with different samples whether the field had depth or distance.

My subjects all denied that it made sense of describe the objects in the field as at any particular distance from them – an inch or a foot or a mile. But I myself confess a temptation to describe my afterimages and eigenlicht as about two inches in front of my subjective center – or right about at the backs of my eyes. Odd! Is that where my subjective center is, two inches behind my eyes? I’m not sure I’d have been ready to say that, until just now. Maybe only for vision?

In the passage quoted in §vi, Koninski says “the visual field appears as regular bluish-(ink-)black grains (the grains millet- to lentil-sized) on a yellow background” (1934, p. 362). Seen as millet- to lentil-sized from how far away? If half an inch, the grains must each occupy a large swath of the visual field – more of the field, probably, than Koninski intends to communicate; if very far away, lentil-sized grains would not be individually distinguishable. So there seems to be an implied intermediate distance – probably more than my two inches. Or could the figures have size without implied distance – angular size only, perhaps?

C.E. Ferree writes:

When one sits with lightly closed lids, which must be kept from quivering, before a bright, diffuse light, such as that of a partly clouded sky, and looks deep into the field of vision thus presented, beyond the background as usually observed, one sees about the point of regard, after the field of vision has steadied, slowly moving swirls (1908, p. 114-115).

Deep into the field? E.R. Jaensch writes:

We turn now to the localization of mental images with closed eyes. Beforehand we left the observers with closed eyes to observe and describe their eigengrau. This term was first clearly explained to the observers. Most described the eigengrau as a more or less gray or black “surface” (“fläche”), others as a gray or black “space” (“raum”). One of the subjects described her eigengrau as if she had the impression of “whirling dust”, another indicated it as an “infinity”, in which color and brightness were not at all explicable. Afterward, we invited them to allow a mental image to any type to form and close their eyes. We then asked in what relationship the mental image stood to the eigengrau. The results were that with closed eyes the mental image was for some observers clearer, for others less clear, and for some it disappeared. All, however, who could see the mental image with closed eyes put it in a spatial relationship with the eigengrau. Most saw the image drawn in the eigengrau, others saw it ringed around by the eigengrau so that a more or less dark gray shone through it (1923, p. 52, my trans.).[6]

I wonder – but Jaensch does not tell us – if those who saw the eigengrau as a surface were the ones who saw their imagery as drawn in it, while those who saw it as a space said that the gray of the eigengrau shown through it, though I guess this wouldn’t have to be the case.

xiv.

This last passage raises question of the spatial relationship of sensory visual experience and visual imagery – a relationship not much explored. Jean-Paul Sartre argues that the two cannot co-occur (1940/1972, p. 138). Jaensch seems to imply that they must either appear in different parts of the visual field or compete in the same part. Accounts of visual imagery as transpiring in the same parts of the visual cortex as ordinary sensory vision (Kosslyn et al. 2001) also invite (but perhaps do not compel) us to think of the two as competitive. Hurlburt’s beeper subjects, in contrast, sometimes report experiencing, simultaneously and without interference, both visual imagery and sensory visual experience (1990, esp. p. 48-51).

Three of my five beeper subjects reported at least one sample containing both visual sensory experience and visual imagery simultaneously (see Table 8.1). S1 reported three such occurrences. Contra, Jaensch and Sartre, and more in accord with Hurlburt, he said his sensory visual experience neither interacted with nor seemed to be in any spatial relationship of any sort with his visual imagery. S2 likewise said that his imagery, one the one occasion he reported it as co-occurring with sensory visual experience, was “not in the same co-ordinate space” as his sensory visual experience. S5, in his one report of this type, in contrast with S1 and S2, and in accord with Jaensch, said that the imagery and the sensory experience were “in the same field of space” though “not of a piece”.

Of course, for reasons I’ve expressed in Chapters 3, 6, and 7, we might legitimately be concerned about the accuracy of such reports.

xv.

Most people don’t seem to believe they can control their sensory experience directly, through acts of will (though of course we can control it indirectly, for example by averting our eyes). One can’t form a sensory visual experience of a cross-shape, for example, simply by willing it to be so. Some scholars even make passivity the mark by which sensory experience can be distinguished from imagery (Berkeley 1710/1965; Sartre 1940/1972; Wittgenstein 1967; McGinn 2004). This lack of responsiveness to the will is perhaps one reason to regard the eigenlicht as sensory rather than imagistic.

In 1894, however, Ladd asserted that he and his students could form eigenlicht experiences by direct willing. (The beginning of this passage is the epigraph of this chapter.)

What they were asked to do was briefly this: to close the eyes, allow the after-images completely to die away, and then persistently and attentively to will that the color-mass caused by the Eigenlicht should take some particular form, – a cross being the most experimented with.... Of the sixteen persons experimenting with themselves, four only reported no success; nine had a partial success which seemed to increase with practice and which they considered undoubtedly dependent direction upon volition; and with the remaining three the success was marked and really phenomenal. It should be said, however, that of the four who reported “no success,” only one appears to have tried the experiment at all persistently (p. 351-352; see also Tatibana 1938, p. 129).

If Ladd is correct, then either the eigenlicht is not sensory in the strictest sense or ordinary people can directly will certain types of visual sensory experience.

I can find no recorded attempts to replicate Ladd’s experiment. Here’s my wager: Responses will be variable, laboratory dependent, and difficult to assess. But so also, it seems, is almost everything about our eyes-closed visual experience, and indeed consciousness in general. Shall we give up then, and study something else?

xvi.

Why did the study of the mind begin, historically, with the study of consciousness? And why, despite that early start, have we made so little progress? These two questions can be answered together if we’re victims of an epistemic illusion – if, though the stream of experience seems easily available and like low-hanging fruit for first science, in fact we’re much better designed to learn about the outside world.