File: <siphonapteramed.htm> <Medical

Index> <General Index> Site Description Glossary <Navigate

to Home>

|

Arthropoda:

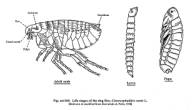

Insecta SIPHONAPTERA (Sucking

Lice) (Contact) Please CLICK on

Images to enlarge & underlined links for details: [Also

See: Siphonaptera Key ] GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS

There are

about 221 genera and over 2,205 species and subspecies of fleas in the

world. The order has five families

with species of medical importance: Hectopsyllidae, Dolichopsyllidae, Pulicidae,

Hystrichopsyllidae and

Ischnopsyllidae. Service (2005)

reported that about 94 percent of species attack mammals while the remaining

species are parasites of birds. Fleas

are also widely distributed all over the world, but the most important

vectors of plague (Yersinia pestis)

occur in the tropics and subtropics.

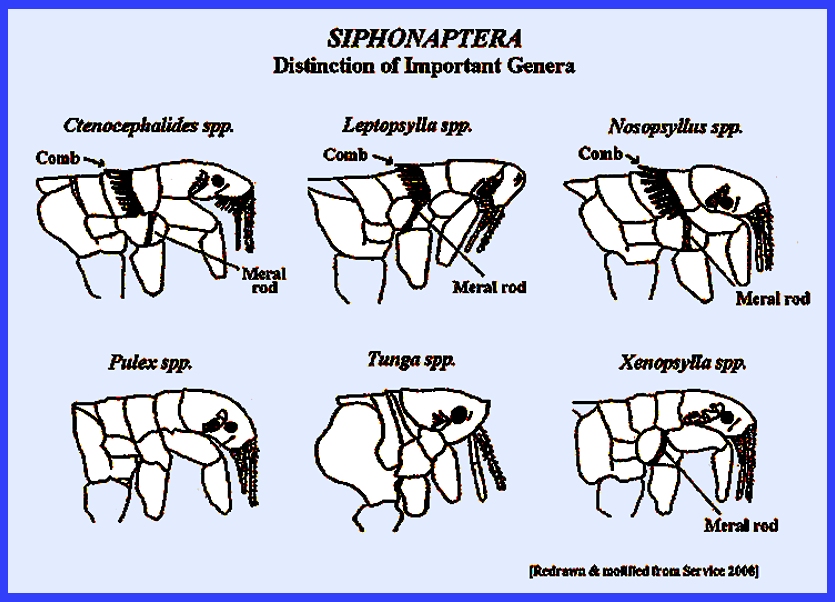

Medically the most important genera are Ctenocephalides. Leptopsylila.

Nosopsyllus. Pulex. Tunga smfXenopsylla. Their combs and meral

rod can identify them: Thirteen

species which are of medical importance include: Ctenocephalides canis

(Curtis) [dog flea], Ctenocephalides felis

(Bouche) [cat flea], Cediopsylla simplex (Baker) [rabbit flea], Ceratophyllus

gallinae (Schrank) [chicken or hen flea], Ctenophthalmus pseudargyrtes

Baker [Small mammal flea], Echidnophaga gallinacea (Westwood) [stick tight flea], Hoplopsyllus anomalus Baker [rodent flea], Leptopsylla segnis [European mouse flea], Nosopsyllus fasciatus (Bosc.) [rat flea], Oropsylla montana (Baker) [ground squirrel flea], Pulex irritans L. [flea of humans], Tunga penetrans L. [jigger flea] and Xenopsylla cheopis (Roth.) [Oriental rat flea]. The common names of fleas (e.g. "dog flea") are

misleading as humans may also be attacked by any of these species especially

when in close proximity of the preferred host. New discoveries of medically important species are being made

in South America; e.g., Ectinorus insignis

(Beaucournu et al 2013) and Ctenidiosomus

sp. (Lopez-Berrizbeitia et al. 2015).

to one other order, the Diptera, by certain aspects of

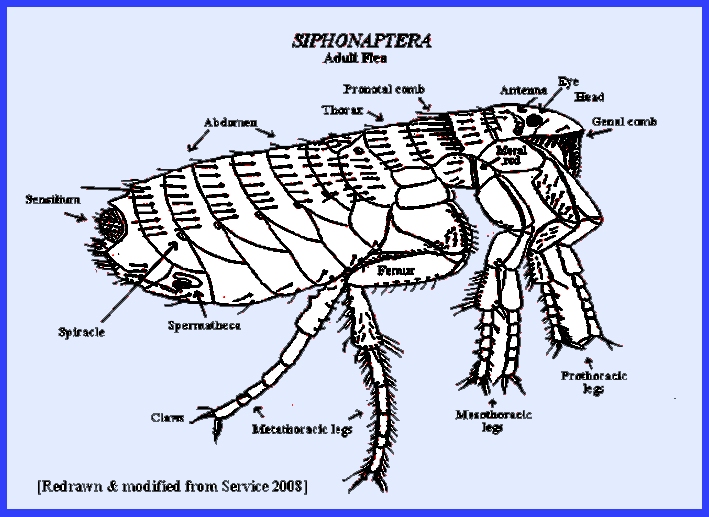

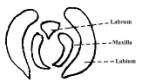

their metamorphosis and somewhat by their mouthparts. The

mouthparts are made up of a pair of long serrated mandibles, a pair of short

triangular maxillae with palps, and a reduced labium with palps. There is a

short hypopharynx and a larger labrum-epipharynx similar to that of the

Diptera. The labial palps, held together, serve to support the other parts, a

function which is performed by the labium in the Diptera. In piercing the

host, the mandibles are most important and blood is drawn up a channel formed

by the two mandibles and the labrum-epipharynx (Borradaile & Potts, 1958). The thoracic

segments are free and wings are absent. Although the eggs are laid on the

host they soon fall off and are afterwards found in little-disturbed parts of

the host's habitat. Therefore, in

houses they reside in dusty carpets and unswept corners of rooms. In a few days the larvae hatch and feed on

organic debris. The legless and

eyeless larvae possess a well-developed head and a 13-segmented body. At the end of the third larval instar a

cocoon is spun and the flea changes into an exarate pupa from which the adult

emerges. The whole life cycle takes

about a month in the case of Pulex

irritans..

Pulex irritans is the

common flea of European houses, but by far the most important economically is

the oriental rat flea, Xenopsylla cheopis,

which transmits Bacillus

pestis, the bacillus of plague, from the rat to humans. This bacillus lives in the gut of the flea

and the faeces deposited on the skin of the host are rubbed into the wound by

the scratching which follows the irritation from the bite. Ceratophyllus fasciatus, the European

rat flea, also transmits the plague organism as can also Pulex irritans, but since the latter

does not live successfully on rats, it is a less dangerous vector (Borradaile

& Potts, 1958). Detailed Habits & Morphology All members

of the Siphonaptera feed exclusively on warm-blooded animals. Their mouthparts lack mandibles and a

siphon is formed of structures of the labrum, labium and maxillae. The labium is an elongated and fleshy covering mechanism. The maxillae are interlocking and a

maxillary sheath is present but not obvious.

A labrum is also present. Fleas are apterous but their extinct

ancestors are known to have possessed wings, which was deduced from pleural

plates on the thorax. Hair-like

structures called geocomb and corolla comb, are present on the

head. The antennae have three segments

and lie in a groove on the head (see ent159). The larvae are eruciform (wormlike)

with a distinct head capsule. They do

not possess legs but leg-like setae instead.

Larvae are not parasitic.

There is an exarate pupa formed in a cocoon (see ent160). Their general

pest status of humans and domestic animals and their ability to vector

diseases makes them of great economic importance. Role as Parasites. -- Fleas are well adapted to the parasitic

habit by being laterally compressed.

They also have a very hard exoskeleton, their legs are developed for

leaping and the hairs on their body are directed backward. Service

(2008) pointed out that the role fleas have in transmitting plague involves

certain important characteristics as follows: Saliva, with

anticoagulants, is passed to the host during feeding, and the blood enters

the pharynx, esophagus and proventriculus, where there are a lot of spines

that are pointed to the rear. These

spines may prevent blood regurgitation of t blood into the esophagus. The proventriculus is important in the

mechanism of plague transmission." Then the blood passes into a large

stomach for digestion. The posterior intestines form a small widened rectum

with rectal glands that remove water so that the faeces are dry. Both male and female fleas suck blood and

can serve as vectors of plague. ----------------------------------------------- Diseases Transmitted by Siphonaptera Bubonic Plague. -- The vector of Pasteurilla pestis is the rat flea. This bacillus wiped out one quarter of the

population of London, England. The

fleas search out other hosts as soon as the rat dies. Transfer is accomplished by (1) defecation

on the body and the inoculum is scratched into the wounds, and (2) the flea

cannot digest the bacillus, so it regurgitates into the wound made by its

mouthparts. Cat-Scratch Disease. -- Bartonella henselae

occurs in cat fleas and can infect humans through a cat's claws if

contaminated. Chigger Infection. -- The

fertilized female flea burrows under the skin and becomes extremely

distended. A serious tropical form is

known as Tunga penetrans. Murine Typhus. -- This

typhus is caused by Rickettsia typhi.

It is transmitted when infected faeces come into contact with

abrasions or mucous membranes. Faeces

retain infectivity of months or years.

The disease primarily affects rodents, especially rats. It is spread by species of Xenopsylla, Nosopsyllus

and Leptopsylla. Different species of Rickettsia may also cause typhus in

humans. Sylvanic Plague. -- The vectors are fleas that live on rodent hosts. This is actually mild type of bubonic

plague, which is found in Western North America. However, humans may also die from infection. Tapeworms. -- The

tapeworm, Dipylidium

caninum, affecting dogs and cats, can also be transmitted by fleas

to humans. Transmission from animals

can occur through handling. Tularaemia. --

Sometimes Francisella

tularensis may be transmitted to humans by fleas even though ticks

are the principal vectors. CONTROL OF SIPHONAPTERA The problem

of controlling fleas involves several distinct measures as advised by

Matheson (1950): (1) control on

domestic pets and in the home; (2) control of fleas on poultry and domestic

animals and in their living areas; (3) control of fleas on rats and other

wild rodents that are sources of plague; (4) prevention of the spread of

plague by restricting the movement of flea carriers. In buildings cleanliness is very

important. Unclean carpets, crevices,

kitchens, bathrooms, closets, cellars, etc. are all places where fleas may

breed. The commercial treatment with

insecticides may be required to reduce flea numbers, or even the fumigation

of an entire building could be necessary. (See Hinkle et al. in References for new

control approaches). = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = Key References: <medvet.ref.htm> <Hexapoda> Azad, A. F. 1990.

Epidemiology of murine typhus.

Ann. Rev. Ent. 35: 553-69. Azad, A. F. & C. B.

Beard. 1998. Rickettsial pathogens and their arthropod

vectors. Emerging Infectious Diseases

4: 179-86. Beaucournu, J.-C.

2013. A new flea, Ectinorus insignis n. sp. (Siphonaptera,

Rhopalopsyllidae, Parapsyllinae), with notes on the subgenus Ectinorus

in Chile and comments on unciform sclerotization in the superfamily

Malacopsylloidea. Parasite 20(35). Bishopp, F. C. 1931.

Fleas and their control. U.S.

Dept. Agr., Farmers' Bull. 897. Bossard, R L; Hinkle, N

C; Rust, M K. 1998. Review of insecticide resistance in cat

fleas (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). J. Medical Entomol.

35(4): 415-422. Eisle, M. , J. Heukelbach &

van Marck, E. et al. 2003. Investigations on the biology, edpidemiology, pathology and

control of Tunga penetrans in Brazil: I. Natural history in man.

Parasitology Res. 49: 557-65. Ewing, H. E. 1924.

Notes on the taxonomy and natural relationships of fleas, with

descriptions of four new species.

Parasitology 16: 341-254. Ewing, H. E. & I.

Fox. 1943. The fleas of North America.

U.S. Dept. Agr. Misc. Pub. 500. Fox, Irving. 1940.

Fleas of the eastern United States.

Ames, Iowa Press Gage, K. L. & Y.

Kosoy. 2005. Natural history of plague: perspectives

from more than a century of research.

Ann. Rev. Ent. 50: 505-28. Gratz, N. G. 1999.

Control of plague transmission:

Plague Manual: Epidemiology, Distribution, Surveillance & Control. WHO, Geneva. pp. 97-134 Hechemy, K. E. & A. F. Azad. 2001. Endemic

typhus, and epidemic typhus. IN: The Encyclopedia of Arthropod-Transmitted

Infections of Man and Domesticated Animals. CABI, pp. 165-69 & 170-74. Heukelbach, J., A. M. L. Costa, T. Wilcke & N.

Mencke. 2004. The animal reservoir of Tunga penetrans in severely affected

communities of north-east Brazil. Med. & Vet. Ent.

18: 329-35. Heukelbach, J., A. Franck & H.

Feldmeier. 2004. High attack rate of Tunga penetrans (L. 1758) infestations

in an impoverished Brazilian community. Trans. Roy

Soc. Trop. Med. & Hyg. 98: 43-44. Hinkle, N. C., P. G.

Koehler, W. H. Kern & R. S. Patterson.

1991. Hematophagous

strategies of the cat flea (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). Florida Ent. 73: 377-85. Hinkle, N. C., P. G. Koehler & R.

S. Patterson.1995. Residual effectiveness

of insect growth regulators applied to carpet for control of cat flea (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae) larvae. J. Econ. Ent. 88: 903-6. Hinkle, N C; Koehler, P G; Patterson,

R S. 1998. Host grooming efficiency

for regulation of cat flea (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae) populations. J. Med. Ent. 35(3: 266-69. Hinkle, N.C., M.K. Rust and D.A.

Reierson. 1997. Biorational approaches to flea

(Siphonaptera: Pulicidae) suppression: present and future. J. Agric. Entomol. 14(3): 309-321. Hubbard, C. A. 1947.

Fleas of western North America.

Ames, Iowa Press. Lopez-Berrizbeitia,

M. F. et al. 2015. A new flea of the genus Ctenidiosomus (Siphonaptera, Pygiopsyllidae) from Salta

Province, Argentina. Zoo Keys

512: 109-20. Matheson, R. 1950. Medical Entomology. Comstock Publ. Co, Inc. 610 p. Pugh, R. E.

1987. Effects on the

development of Dipylidium caninum

and on the host reaction to this parasite in the adult flea (Ctenocephalides felis felis).

Parasitol. Res. 73: 171-77. Rothschild, N. C. 1910.

A synopsis of the fleas found on Mus

norvegicus, Mus rattus

and Mus musculus. Bull. Ent. Res. 1: 89-98. Rust, M. K. 2005.

Advances in the control of Ctenocephalides

felis (cat flea) on cats and dogs. Trends in Parasitol. 1:

232-36. Rust, M. K. & M. W.

Dryden. 1977. The biology, ecology and management of the

cat flea. Ann. Rev. Ent. 42: 451-73. Rust, M.K., I. Denholm, M.W. Dryden,

P. Payne, B.L. Blagburn, D.E. Jacobs, N. Mencke, I. Schroeder, M. Vaughn, H.

Mehlhorn, N.C. Hinkle, and M. J. Med. Entomol. 42(4): 631-636. Rust, M.K., I. Denholm, M.W. Dryden, P. Payne, B.L.

Blagburn, D.E. Jacobs, N. Mencke, I. Schroeder, M. Vaughn, H. Mehlhorn, N.C.

Hinkle, and M.

Williamson. 2005. Determining a diagnostic dose for

imidacloprid susceptibility testing of field-collected isolates of cat fleas (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). Journal of Medical Entomology 42(4):

631-636. Schriefer, M. E., J. B. Sacci, J. P. Taylor, J. A.

Higgins & A. F. Azad. 1994. Murine typhus: updated roles of multiple

organ components and a second

typhus like rickettsia. J.

Med. Ent. 31: 681-85. Service, M. 2008.

Medical Entomology For Students.

Cambridge Univ. Press. 289 p Scott, S. & C. J.

Duncan. 2001. Biology of Plagues: Evidence from Historical Populations. Cmbridge Univ. Press, England. Traub, R. & H. Starcke (eds.) 1980. Fleas. Proc. Intern.

Conf. on Fleas, Ashton Wold, Peterborough, UK, 21-25 Jun 1977. Rotterdam: Balkema. |