sFile: <tabanidaekey.htm> <Medical

Index> <General Index> Site Description <Navigate to Home>

|

MYIASIS-CAUSING

ARTHROPODS KEY (Contact) ----Please

CLICK on desired highlighted categories to

view: Use Ctrl/F to search for subjects:

[Also

See: Key to Myiasis-causing Flies]

Service

(2008) considered different types of myiasis caused by Diptera as accidental,

obligatory or facultative. The accidental type comes about by

eating contaminated food containing eggs or larvae, which can lead to

discomfort in humans and more serious effects in animals. The obligatory type of myiasis requires that fly maggots live in the

host for all or part of their life cycle.

Facultative myiasis

results when larvae that are generally free-living also infect living

hosts. Throughout the literature

different terms are used to describe myiasis that affects different parts of

the body. Service (2008) gave the

following examples: Cutaneous = dermal or subdermal

myiasis; Urogenital myiasis; Ophthalmic = ocular myiasis; Nasopharyngeal myiasis; and Intestinal = gastrointestinal or

enteric myiasis. Referring to

appearance, there is Creeping Myiasis;

Furuncular Myiasis = boil-like

lesions occur; and Traumatic Myiasis

= when wounds are infested with living larvae. Matheson

(1950) noted that different names have been applied to the myiasis caused by

insect species in the different orders.

The term myiasis is

used for the Diptera that are responsible for the majority of cases, whereas

for Coleoptera it is canthariasis

and for Lepidoptera it is scoleciasis. The latter two types are comparatively

rare in humans. There are accidental cases of

myiasis involving Coleoptera, many of which are also of doubtful

validity. Matheson (1950) discusses

the larvae of Dermestidae and Tenebrionidae where infection might occur

through the consumption of cold cereals.

Most of these refer to Tenebrio

molitor, the mealworm, which is an important host of tapeworm,

Hymenolepis diminuta. Other beetle species that have been

associated with myiasis are Attagenus piceus

, Onthophagus bifasciatus,

O. unifasciatus, Caccobius mutans (see Caccobius

sp.), and Ptinus tectus. The larvae of

Lepidoptera have been connected with myiasis in a few rare cases, although

there is some doubt about their accuracy.

Matheson (1950) presented one more reliable case of a child who

consumed raw cabbage and later vomited larvae of the cabbage butterfly, Pieris brassicae. Church (1936) recorded a case where larvae

of the Corn Borer, Pyrausta nubilalis,

had attacked the body tissues of a woman. MYIASIS -- By Diptera There are

many authenticated cases of myiasis being caused by Diptera (flies). The Posterior Spiracular Plates

and Cephalopharyngeal Skeletons

of some Diptera larvae are used for identification (See: Key to

Myiasis-causing Flies. The following are arranged by separate

Diptera families: Sarcophagidae -- flesh Flies Sarcophagidae

adults are very abundant everywhere around decaying vegetation, animal matter

and excrement. Most species lay live

larvae and not eggs. Among the many

varied habits some species are parasitic on warm-blooded animals, on

grasshoppers and snails. Many are

scavengers and others are attracted to wounds. Because identification of larvae can be difficult it is best to

rear encountered larvae to the adult stage for proper identification. Larvae of the

genus Wohlfahrtia is frequently

involved in myiasis. One species, Wohlfahrtia vigil

Walker being unique among the Sarcophagidae by attacking healthy skin rather

than wounds or body orifices. Wohlfahrtia opaca Coq. of America and W. magnifica

Schiner of Europe are other important species in the genus but they

characteristically attack open wounds. The

cosmopolitan Sarcophaga haemorrhoidalis

Fall and other infecting species, S.

fuscicauda Keilin and S.

sarraceniae Riley,

are occasionally found important in causing myiasis particularly in the

intestinal tract.. Calliphoridae --

blowflies, bottleflies Callitroga americana (Cushing & Patton) is the screwworm fly is important

all over the Americas. It is an

obligate parasite of humans and animals that deposits larvae in open

wounds. Mortality rates are very high

among animals that it attacks, and humans can also perish if not treated

promptly. Callitroga macellaria (Fabr.), or secondary screwworm resembles C. americana, and

it is also widely distributed in the Americas. They usually deposit eggs on carrion but will also oviposit in

the wool of sheep and on wounds, and possibly on humans although this is

doubtful as there is confusion with C.

americana. Chrysomya bezziana is related to screwworm fly, but it is most common in

Africa, Asia and the Philippines. It

prefers to infest wounds of animals, but occasionally will attack humans

also. Other species of Chrysomya that occasionally attack

humans are C. marginalis

(Wied.) in Africa and C. albiceps

(Wied.), while in Europe, India and Africa, C.

chloropyga (Wied.) and C.

rufifacies (Macq.) are of some concern. Calliphora vomitoria (L.), C. vicina

R.-D. and C. livida Hall are common

bottle- or blowflies that cause myiasis by ovipositing in open wounds of

animals and occasionally humans. They

complete their life cycles from egg to adult in 2-4 weeks. In the genus Lucilia, which includes the green-bottle

flies, there are a number of species of medical importance because of their

involvement in myiasis. Included are C. americana (L.),

L. sericata Meig., L. illustris (Meig.),

L. cuprina (Wied.)

and L. silvarum (Meig.). Although myiasis has been attributed to

these flies under the species names noted, their identifications may be

inaccurate. Cordylobia anthropophaga (= Tumbu or Mango Fly) and Auchmeromyia

senegalensis (= Congo floor maggot) of Africa. Infestation occurs from contaminated

clothing that has not been washed or is placed on the ground to dry. The larvae of

Cordylobia anthropophaga

Grunberg, the tumbu fly of Africa, that begin their growth in decaying

organic matter, will penetrate the skin of animals and occasionally humans to

complete their development. Phormia regina (Meig.), the black blowfly, is a cosmopolitan species that

causes myiasis in animals and rarely in humans. Auchmeromyia luteola (Fab.), the Congo floor maggot, larvae attack humans by

feeding on their blood during the night.

They leave their hosts in daytime only to return again to feed at

night. Pollenia rudis (Fab.), the cluster fly, does not cause myiasis but annoys

people when adults enter dwellings.

In this case they are parasitic on earthworms. Musca domestica L., the common housefly, has caused intestinal myiasis in

humans. Infection can occur because

of this fly's close association with humans in their dwellings. Matheson (1950) details the many

situations where infection can occur, which are usually through a lack of

sanitation. Muscina stabulans (Fallen), the nonbiting stable fly, is sometimes abundant

around structures. Its habits are

similar to Musca domestica by

breeding in organic wastes, and it also has caused intestinal myiasis in

humans. Fanniidae (=Anthomyiidae) -- lesser

houseflies Species of

the genus Fannia often occur

together with Musca domestica

in the same habitats of decaying organic matter. Adults of Fannia canicularis (L.), the lesser

housefly, will occur in large numbers hovering in and outside of

structures. These flies are

particularly abundant where poultry dung provides an ideal breeding habitat. Fannia scalaris

Fab., the latrine fly, is smaller than F.

canicularis and with similar breeding habits. Matheson (1950) reports the existence of

numerous records where the larvae of these flies caused gastric and

intestinal myiasis in humans. Oestridae -- bot- & warble

flies This group of

flies is usually associated with domestic and wild animals, but there are

occasional cases of myiasis in humans.

Four subspecies are involved:

Oestrinae, Gastrophilinae, Hypodermatinae & Cuterebrinae. Two genera of particular medical importance

are Oestrus and Rhinoestrus. When humans come in close contact with sheep and other domestic

animals they may become infected (e.g., Oestrus

ovis L.). Adults of the

subfamily Cuterebrinae resemble

bees, and the larvae of all species are parasitic on mammals including

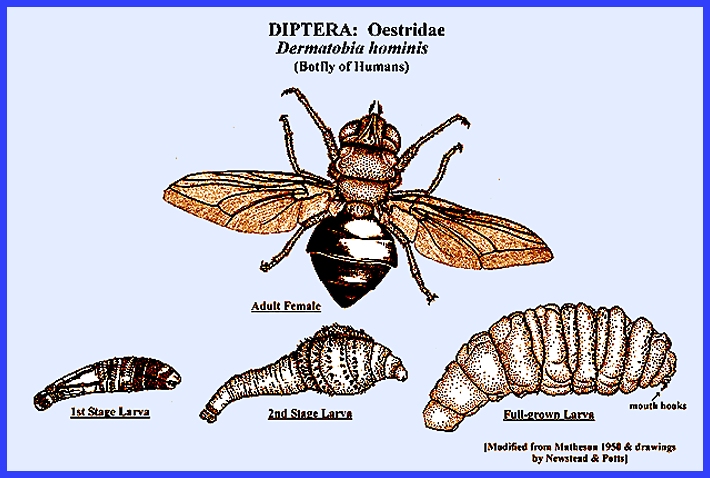

humans. Dermatobia

hominus.L, the human warble fly, is common especially in

forested regions of tropical America.

Females of this species infest other arthropods such as mosquitoes,

flies and ticks, with their eggs.

Humans become infected when coming into contact with the carriers. The warble fly eggs hatch when the carrier

contacts the host, and the larvae burrow into the skin, which is facilitated

by wounds caused by the carrier. One Cuterebra sp. has also been found to

attack humans. Hypoderma bovis L. & Hypoderma

lineatum (Villers) are the more common cosmopolitan warble

flies attacking cattle. However,

parasitism of humans is not uncommon, and infection is noticeable when the

larvae produce a swelling underneath the skin. Both Matheson (1950) and Service (2008) present detailed cases

of human infection and frequent encounters with Hypoderma

bovis. Botflies in

the subspecies Gastrophilinae resemble honeybees. Gasterophilus intestinalis,

G. haemorrhoidalis and G. nasalis are often found to attack humans. There are

many species in this Diptera family, all of which resemble bees. Tubifera

tenax (L.), the drone fly, is found hovering around rotting

organic matter upon which eggs are deposited. The larvae are distinctive because of a tail-like breathing

tube, giving them the name "rat-tailed maggots." There have been numerous cases of intestinal

myiasis recorded from humans with this species. Matheson (1950) stated that infection with these larvae would

probably have come from drinking fouled water containing young larvae or eggs

or ingesting rotting fruit. Other

less common species of Tubifera

that are suspected to have caused myiasis are T. argustorum and T.

dimidiatus. There are

also reported cases of intestinal myiasis caused by Syrphus species even though the group is

predacious on other insects.

Infection with this group is believed to result from ingesting

contaminated vegetables. On rare

occasions other Diptera species have been reported in cases of myiasis. Most often found are Psychoda albipennis and P. bipunctata Curt. (Psychodidae), Megaselia scalaris

(Phoridae), Piophila casei (Piophilidae), Rhyphus fenestralis Scop.

(Anisopodidae), Hermetia illucens L.

(Stratiomyidae). [See Matheson 1950 for more details]. In the 20th

Century the larvae of blowflies had been used in the treatment of

osteomyelitis by devouring dead and dying tissues and simultaneously

destroying any invading bacteria.

Thoroughly cleaned wounds hastened the healing process and the

larvae's saliva apparently possessed bactericidal properties. When myiasis

involves living larvae occurring in sores, wounds and dermal or sub dermal

tissues, their removal under aseptic conditions can be quite simple. However, when the larvae are deeper in the

tissues or when they have affected the mucous membranes, frontal sinuses or

eyes, removal can be complicated so that surgery may be required. In extreme cases the larvae may cause

major damage that cannot be undone. An accurate

diagnosis of the causative agents may be useful in the treatment of myiasis,

but infection should be precluded by a thorough knowledge of the environment

to avoid contaminated foods and the vector carriers of eggs or larvae

involving other arthropods such as mosquitoes and ticks. The use of insect repellants and proper

clothing can protect against contact.

Also there may be seasonal activity of vectors that can be avoided. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Key References: <medvet.ref.htm> <Hexapoda> Abram, L. J. & A. I. Froimson. 1987.

Myiasis (maggot infection) as a complication of fracture management: a

case report and rev.of literature. Orthopedics 10: 625-27. Aldrich, J. M. 1916.

Sarcophaga and allies in

North America. Thomas Say Found. Ent.

Soc. Amer. Andre, Emile. 1925. Sur un cas de

myiase cutanee chez l'homme.

Parasitology 17: 173-75. Arbit, E., R. E. Varon & S. S.

Brem. 1986. Myiatic scalp and skull infection with

Diptera Sarcophaga: a case

report. Neurosurgery

18: 361-62 Austen, E. E. 1912. British flies which cause myiasis in man. Rept. Local Govt. Bd. Pub. Hlth & Med.

66: 5-15 Baer, W. S. 1931.

The treatment of chronic osteomyelitis with the maggot (larva of

blow-fly). J. Bone & Joint Surg.

13: 438-475. Beckendorf, R., S. A. Klotz, N. Hinkle

& W. Bartholomew. 2002. Nasal myiasis in an intensive care unit

linked to hospital-wide mouse infestation.

Archives Internal Medicine 162:

638-640. Brand, A. F. 19031.

Gastro-intestinal myiasis.

1931. A report of a case. Arch.

Internal. Med. 47: 149-154. Catts, E. P. 1982.

Biology of New World bot flies:

Cuterebridae. Ann. Rev. Ent.

27: 313-38. Colwell, D. D., M. J. R. Hall & P. J. Scholl

(eds.) 2006. The Oestrid Flies:

Biology, Host-Parasite Relationships, Impact & Management. CABI, Wallingford. Dixon, O. J. 1924.

An unusual case of rhinal myiasis with recovery. J. Amer. Med. Assoc. 83: 1332-1333. Dove, W. E. 1937.

Myiasis of man. J. Econ. Ent. 30: 29-39. Gabaj, M. M., A. M. Gusbi & M. A. Q. Awan. 1989. First human infestations in Africa with larvae of the American

screwworm, Cochliomyia hominivorax Coq.

Ann. Trop. Med. & Parasitol. 83:

553-54. Graham, O. H. (ed.) 1985. Symposium on eradication of the

screwworm from the United States & Mexico. Misc. Publ. Ent. Soc. Amer. 62: 1-68. Greenberg, B. &

J. C. Kunich. 2002. Entomology and the Law: Flies as Forensic

Indicators. Cambridge Univ. Press. Hall, M. J. R. & R.

Wall. 1995. Myiasis of humans and domestic animals. Adv. Parasitol. 35: 257-334. Hinman, F. H. & E.

C. Faust. 1932. The ingestion of the larvae of Tenebrio molitor L. (meal worm) by

man. J. Parasit. 19: 119-20. Hope, F. W. 1840.

On insects and their larvae in the human body. Trans. Ent. Soc. London 2: 256-271. Kersten, R., N. M.

Shoukrey & K. F. Tabbara.

1986. Orbital myiasis. Ophthalmology 93: 1228-1232. Krafsur, E. S., C. J.

Whitten & J. E. Novy. 1987. Screwworm eradication in North and Central

America. Parasitology Today 3: 131-137. Lane, R. P., C. R. Lovell, W. A. D. Griffiths &

T. S. Sonnex. 1987. Human cutaneous myiasis: a review and

report of three cases due to Dermatobia

hominis. Clinical &

Exptal. Dermatol. 12: 40-45. Legner, E. F. 1995.

Biological control of Diptera of medical and veterinary

importance. J. Vector Ecology 20(1):

59-120. Legner, E. F.. 2000.

Biological control of aquatic Diptera. p. 847_870.

Contributions to a Manual of Palaearctic Diptera, Vol. 1, Sci. Herald, Budapest. 978 p. Liggett, H. 1931.

Parasitic invasion of the nose.

J. Amer. Med. Assoc. 96:

1571-72. Lindner, E., 1930. 1a. Phryneidae (Anisopodidae, Rhyphidae). In: E. Lindner, Die Fliegen der palaearktischen Region,

vol. 2, pt. 1. Stuttgart, 10 pp. Matheson, R.

1950. Medical Entomology. Comstock Publ. Co, Inc. 610 p. Meillon, B. de. 1937. A note

on two beetles of medical interest in Natal.

S. Afr. Med. J. p. 479. Meleny, H. E. & P. D. Harwood. Human intestinal myiasis due to the larvae

of the soldier fly, Hermetia illucens

Linne. Amer. J. Trop. Med. 15: 45-49. Nunzi, E., F.

Rongioletti & A. Rebora.

1986. Removal of Dermatobia hominis larvae. Archives of Dermatol. 122:

140. Palmer, E. D. 1946. Intestinal

canthariasis due to Tenebrio molitor. J. Parasitol. 32: 54-55. Service, M. 2008. Medical

Entomology For Students. Cambridge

Univ. Press. 289 p Sharpe, D. S. 1947.

An unusual case of intestinal myiasis. British Med. J. 1: 54. Sherman, R. A., M. J. R. Hall & S. Thomas. 2000.

Medicinal maggots: an ancient remedy for some contemporary

afflictions. Ann. Rev. Ent. 45: 55-61. Shoaib, K. A. A., P. J. McCall, R. Goyal, S.

Loganathan & W. D. Richmond.

2000. First urological presentation

of new world screw worm (Cochliomyia

hominovorax) myiasis in the

United Kingdom: a case report.

British J. Urology-International 86:

16-17. Smith, K. G. V. 1986.

A Manual of Forensic Entomology.

British Mus. Nat. Hist. & Cornell Univ. Press pp.

93-137. Spradbery, J. P. 1991.

A Manual for the Diagnosis of Screw-Worm Fly. CSIRO, Div. of Entomology. Zumpt, F. 1965.

Myiasis in Man and Animals in the Old World: a Textbook for

Physicians, Veterinarians and Zoologists.

Butterworth Publ., London. |