File:

<acanthocephala.htm> <Index to Invertebrates> <Bibliography> <Glossary> Site Description

<Navigate to Home>

|

Invertebrate

Zoology Kingdom: Animalia, Phylum: Acanthocephala (Contact)

CLICK on underlined file names and included illustrations to

enlarge: The Phylum Acanthocephala derives its name from

"spiny-headed." All species

are parasites in the digestive tract of vertebrates with intermediate hosts

that are generally arthropods. The

anterior end of the animal has a probosis with spiny hooks. A representative genus is Macracanthorhynchus

with characteristics noted as follows: General

Body Features.-- A retractable

proboscis is present. There is a

genital pore at the posterior end, which in the female is very simple and in

the male is an inflatable fan-like affair or bursa

that is used for copulation. The

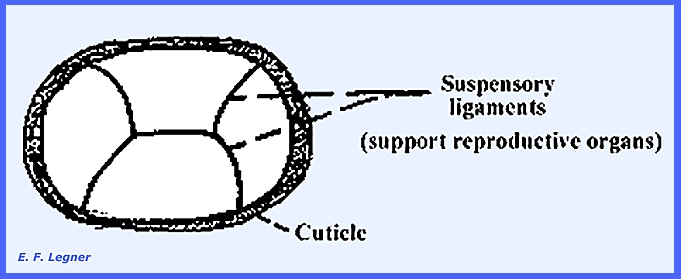

female is larger than the male. Body Wall.-- A heavy

cuticle is present. Underneath the

cuticle and secreting it lies the epidermis.

All cell membranes are lost between the cells, a condition that is

known as a syncytium. In the syncytium nuclei are scattered

through an undivided mass of cytoplasm.

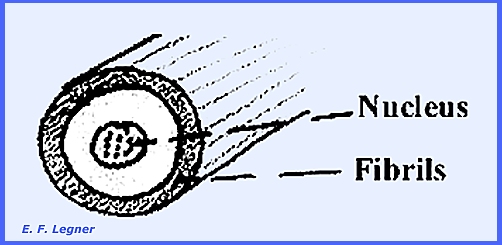

Both circular and longitudinal muscles are well developed and lie

under the epidermis. The muscle cells

consist of tapering hollow cylinders . Pseudocoelom.--

This structure differs from a true coelom in not being derived entirely from

the mesoderm. In a true coelom the

body cavity is lined on all sides by mesoderm. However, it serves the same purpose as a true coelom. It takes up practically all of the

interior of the animal. Inside the

pseudocoelom there is a fluid, which maintains turgor. Food

& Digestion.-- There is no mouth

or any sign of a digestive tract, and thus the animals are similar to the

Cestoda. Predigested food is absorbed

through the body wall. Respiration.--

The animals respire by diffusion and it is anaerobic for considerable

periods. Excretion.--

Flame cells, which are not scattered, accomplishes excretion. They are gathered into two large tufts

projecting out into the pseudocoelom and emptying out through the

reproductive tract (= urogenital system). Nervous System.--

A simple nervous system is present consisting of a single ganglion, which

lies on the outer wall of the proboscis sheath. Various nerves run out to different parts of the body

particularly to the muscles. This is

then much simplier than that of the Turbellaria. Reproduction.-- Extending

the whole length of the body and dividing up the pseudocoelom in sections are

suspensory ligaments. The male has two testes attached to a

suspensory ligament, and the vas eferens and vas deferens are present. There are a series of 6-8 cement

glands

on the sides of the vas

deferens, which lead back to the copulatory bursa that

serves an adhesive funtion during copulation. The female has a series of ovaries

attached to the suspensory ligaments.

Floating ovaries

are present, which are

little patches of ovary tissue that break off of the main ovary and bear the

maturing ova. The eggs when mature

detach from the ovaries and they too float in the fluid of the

pseudocoelom. Eggs are fertilized in

the pseudocoelom by the sperm that enter the cavity. Eggs with developing embryos bear 2-3

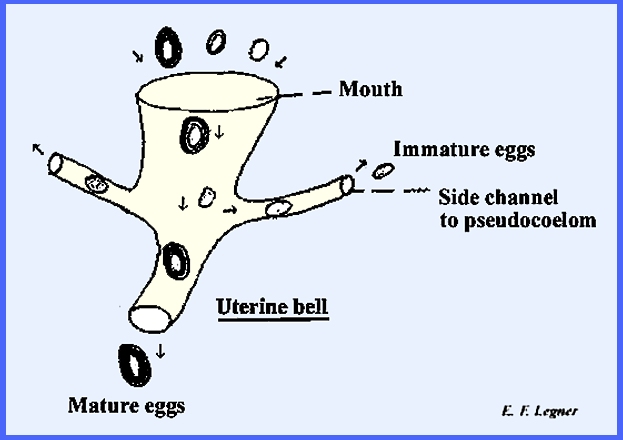

heavy shell layers. At the opening of

the female genital tract is a remarkable structure, the uterine

bell, which is a selective

apparatus. Fluid of the pseudocoelom is

sucked into the mouth of the apparatus.

A selection of mature eggs is made at the base and immature eggs are

passed back into the pseudocoelom.

The mature eggs are laid outside following selection that is made on

the basis of size and shape of the egg. Lemnisci.--

These are glandular structures, which occur at the anterior end of the

animal. They are part of the lacunar

system that runs all through

the epidermis. They may serve as

reservoirs for fluid, which moves around the lacunar system. Cell

Constancy.-- There is a definite

number of cells per each organ, thus the number of epidermal, muscular, nerve

cells, etc. is constant per species.

This results in a cessation of cell division in the late embryonic

period of development, except for the ovaries and testes. All further increase in size is due to the

enlargement of existing cells.

Various parts of the body consist of definite numbers of cells (except

the gonads). Along with this there is

a tremendous increase in the size of the nuclei. A syncytium frequently results. Life

History. -- Macracanthorhynchus is

a parasite of pigs. The eggs pass out

with the host's faeces. June beeetle

larvae consume the eggs and the embryo leaves the egg and bores through to

the body cavity of the beetle. The

hog must devour the beetle to complete the life cycle. Different species of parasite have

different intermediate hosts of aquatic insects and crustaceans, etc. Importance.--

There is relatively little economic importance although infection by Macracanthorhynchus may lower

the general health of pigs if present in large numbers. ------------------------------------ Please see

following plates for Example Structures of the Acanthocephala: Plate 29 = Phylum: Acanthocephala: Macracanthorhynchus

sp. male Plate 30 = Phylum: Acanthocephala: Macracanthorhynchus

sp. -- Cross-sections Plate 31 = Phylum: Acanthocephala, Macracanthorhynchus

sp. -- Dissected Female specimen ============== |