File: <scotogam.htm> <Migrations Index> <Bronze Age Index> <Archeology

Index> <Home>

[Note: All Basque words are in Italics and Bold-faced Green]

|

SCOTLAND’S OGAM INSCRIPTIONS * A review derived from the following: Nyland, Edo. 2001. Linguistic Archaeology: AnIntroduction. Trafford Publ., Victoria, B.C., Canada. ISBN 1-55212-668-4. 541 p. ----Please CLICK on desired underlined categories [to

search for Subject

Matter, depress Ctrl/F ]:

An ancient language form that

originated in the sub-Saharan West African area of our most ancient

civilizations has been studied by Nyland (2001). He found that many words used to describe names

of places and things in Scotland were closely related to the ancient

language, which Nyland called Saharan,

and which later was predated by the Igbo Language of West Africa. Fortuitously, the Basque Language is

a close relative to the original Saharan. Following is a discussion of this relationship: In his book

"The

Symbol Stones of Scotland" (1984), Dr. Anthony Jackson, anthropologist at the University of Edinburgh,

illustrated and transliterated more than thirty Ogam inscriptions found in

Scotland and found that the best of efforts by linguists and others had not

resulted in even one translation. There had been few problems transliterating

them, but no one had been able to do anything with the

"meaningless" series of letters obtained. In October of 1993, Jackson followed

this work with an unpublished monograph called "Pictish Symbol

Stones?" in which he updated his earlier research.

Probably referring to efforts of Henri Guiter, Jackson wrote, "There is a popular theory that they

are Basque but this does not work either" (p.118). Jackson also

commented: "It is

curious that this small number of Ogam inscriptions has caused more headaches

than all the other problems of the Picts put together. As one leading

archaeologist put it: it is not really the fault of the Picts but the

interpreters of the Picts that are to blame! (p. 117). This remark was

so true by Nyland (2001), but Jackson

decided to give up entirely on translating the puzzling writings. He wrote: "All research along

linguistic lines has ground to a halt, unsurprisingly" (p.135) and:

"It is clear that the Ogam inscriptions are numerically based and not

linguistic" (p.153). In other

words he thought they were numerical magic, possibly a form of numerology,

inscribed on the ancient standing stones to overcome the pre-Christian magic:

"thus we seem to have a battle between rival magics" (p. 154). Edo

Nyland agreed with his suggestion that magic is involved, because the

inscriptions are so complicated in design that it is hard to believe that

they were intended to be read by the common people or even by most of the

clergy; they belonged to a very different level of theology. In 1968 a Basque scholar from France,

Henri Guiter, thought he could see Basque words in the transliterated

inscriptions and tried to make sense of some of them. He published two papers

in French, which received mixed reviews such as from Oliver

Padel who could not find the first paper, but

"if one is to judge by the information supplied in the second, this is

no great loss". Another person who criticized Guiter was Douglas

Gifford, Dept. of Spanish of St. Andrew’s University in Scotland. In a 1969

radio talk, he said that Guiter had twisted the evidence, but also suggested

that the Basque connection was worth a further look. Nyland then took this

‘further look’ and decided to include Guiter’s work in this article because

his approach was so very different from anyone else’s. The reader will see

that his translations appear to make little sense. The people who composed

the inscriptions were a great deal more sophisticated linguistically and

mathematically than our modern scholars have ever given them credit for.

Guiter’s effort had also been published in Spanish in a booklet called

"Garaldea" by Federico Krutwig and the Spanish translations of Guiter’s effort are shown

here. Dr. Gifford’s

suggestion that Basque could well be the language of the Ogam inscriptions

was supported by genetic and linguistic evidence in Ireland and Scotland.

Geneticist Dr. Cavalli-Sforza from Stanford University had published a world

map in Scientific American (Nov. 1991), showing the distribution of the

Rh-negative people. The populations with the highest proportion of their

members with Rh-negative blood were found among the Berbers

in Morocco, the Basques in Euskadi, and the dark featured peoples of Northern

Ireland and Scotland, all with over 25% of the people with this blood

peculiarity. He commented "... the resulting pattern roughly coincides

with anthropological reconstructions of ancient migrations." Of these

four groups, only the Basques still spoke their pre-Christian language. It

was therefore reasonable to suggest that the entire migration had spoken this

language. This possibility was crying out for proof. Fortunately a very large

number of early inscriptions on stone, silver, brass, bone etc. were

available; over 600 in Ireland and some 40 in Scotland. None of these

inscriptions had ever been translated with certainty. Transliteration from

the Ogam script had not been a problem, but only an apparently meaningless

series of letters, mostly consonants, had been obtained. However, as

considerable time and effort must have gone into making these

inscriptions. Edo Nyland assumed that

some system of decoding had to exist. [= Vowel Consonant Vowel ] From the moment

that Edo Nyland tackled the problem, it appeared likely that most of the

vowels had been removed for some good reason, based on a certain pattern.

After a great deal of experimentation, it was found that the basic pattern

had to have been VCVCVCV etc. This letter-pattern looked strikingly like that

of thousands of Basque words such as: "ohitura" (custom).

But, Basque being an agglutinated language, this word in itself was composed

of three other roots, ohi-itu-ura: ohi (habit) itungaitz (disagreeable) urratu (to break), meaning: "Break that disagreeable habit", creating a

VCV-VCV-VCV pattern. In addition, the vowels on either side of the hyphens

were always the same, completing the formula: VCV1-V1CV2-V2CV3-V3CV

etc. Nyland called this the "vowel-interlocking" or "VCV Formula".

Trial and error proved that this was indeed the formula used in every Ogam

inscription examined to date, without exception. For more examples, see "The Saharan Language". Searching for

linguistic evidence of Basque in the family and geographical names of these

countries, in Scotland many family names immediately stood out, e.g: MacKenzie, kentze is the act of

depriving, of taking away, to steal from, probably referring to territory.

The MacKenzie tribe was therefore known by their neighbours as the people who

had conquered or taken something that didn’t belong to them.

it easy".

THE SYSTEM OF

ENCODING AN OGAM INSCRIPTION Procedures for encoding

and decoding Ogam inscriptions were presented by Nyland (2001). 1). In the sentence to be inscribed, use only

those Basque words that start with vowel-consonant- vowel (VCV).

VCV1- V1CV2-V2CV3-etc.

system of prime numbers. (See Jackson

1993, pages 117 - 152).

1) Restore

the original letters: V becomes B, C and Q become K.

placing dots where

vowels were removed. In case of double vowels, an H has usually been removed. Keep in

mind that every consonant represents a word.

therefore starts

with CV.

<Translating Ogam >, and select the words that form

the appropriate sentence. In this section,

all three interpretations by Guiter, Jackson and Nyland

are brought together for each of the inscriptions . Let the reader be the judge. The order in which the

inscriptions are presented is taken from Jackson’s 1993 publication "Pictish

Symbol Stones?” The transliteration used is also taken from Jackson

because his interpretation is superior to any other efforts. Translating Ogam

is certainly no exact science, it is only the best possible approximation. It

may well be that some of the inscriptions were designed to be magical, yet

when they were finally translated, most made good sense from the standpoint

of evangelizing a "heathen" country. Two of the larger

inscriptions, Brodie B and Golspie, in spite of several hours of work, have

so far resisted the decoding process. Some like Altyre and Cille Barra

describe natural disasters that do not refer to evangelism. Aboyne B and

Altyre are grave markers. Strictly adhering to the vowel interlocking between

the VCV roots is the key to decoding the inscriptions. Map

showing the location of the following inscriptions.

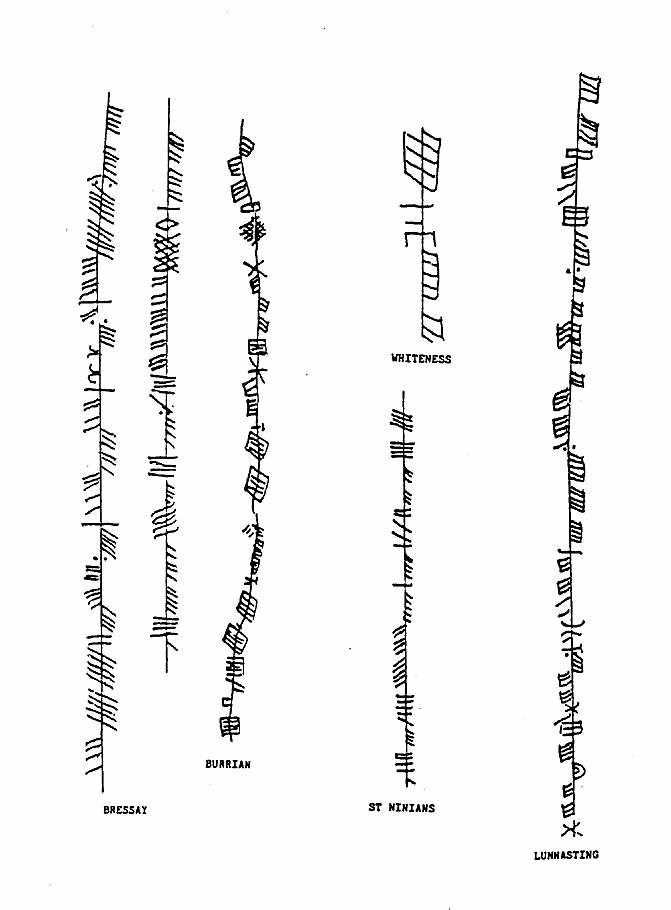

BRESSAY. A) CRROSCC- B) NAHHTVVDDADD -

C) DATTRR - Guiter: Basque reading: Berriz Enekoaren Kroska naiz Udak daragina.

Jackson: A) 28 7x4 75 5x5x3 Nyland:

B: NAHHTBBDDADDS

C: DATTRR

D: ANNBENNISES

The disciples, as well as the flock (Mark 14:50), in general

weakness were mocking during that moment of tribulation (Mark 15:17-20) E: MEOODDRROANN

BURRIAN. IDBMIRRHANNURRAC TEEVVCERROCCS Guiter:

Basque reading: Don kuorari ańu(ti)ra dan kerroke.

Nyland: IDBMIRRHANNURRAKTEEBBKERROKKS

WHITENESS. VNDAR Guiter: No reading. Nyland: BNDAR.

LUNNASTING. A) ETTECUHETTS - B) AHEHHTTANNN - C)

HCCVVEVV - D) NEHHTONN Guiter: Basque reading: Etxekoez aiekoan nahigabe ba nengoen.

Jackson: A 36 6x6 140 7x5x2

Nyland: A: ETTEKUHETTS et. eta etariko

one of our group

B: AHEHHTTANNN ahe aihe aiher

full of anger

C: HKKBBEBB .h.

aha

ahal

I wish

D: NEHHTONN. ne ne nebarrebak

brothers and sisters

The place name Lunnasting itself is

interesting:

ST. NINIANS. BESMEQQNANAMMOVVVEZ Guiter: Basque

reading: Eneko ba nago bez.

Jackson: 54 6x9 172 43x4 Nyland: BESMEKKNANAMMOBBEZ .be be bedeinkagarri blessed one

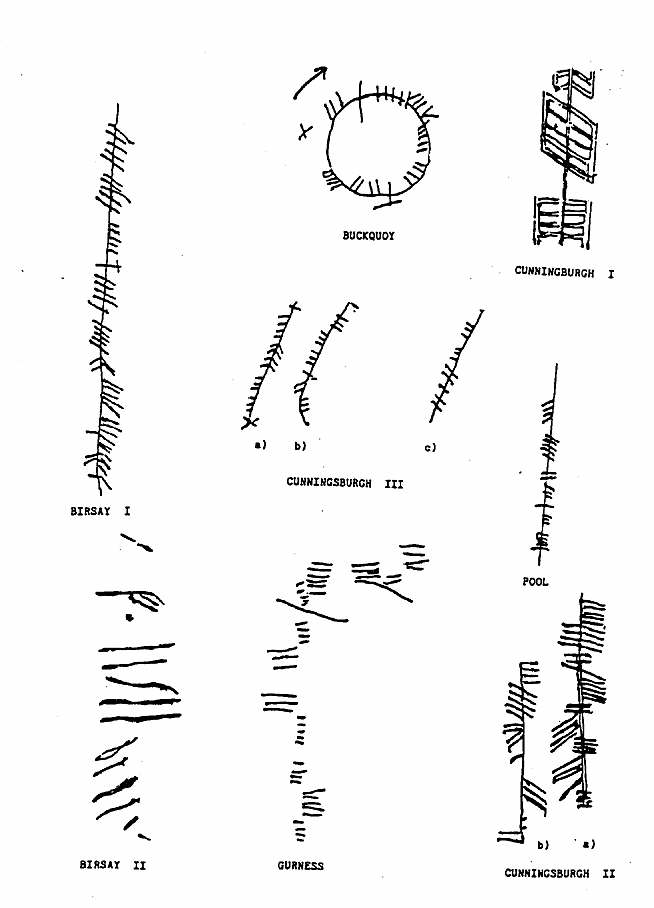

BIRSAY. 1) MBOLMVNORRALVRR - 2) BQIAB Guiter: Basque reading: None. Jackson: 43 prime 170 5x2x17 Nyland: Birsay 1) MBOLMVNORRALBRR m. ma maisu

teacher

despised cross. Birsay 2) BKIAB .b. be bedeinkagarri the blessed one

BUCKQUOY. ETMIQMSSALLC Guiter: Basque reading: None. Jackson: 36 6x6 135 5x3x3x3 Nyland: ETMIKMSSALLIK et. eti etika

ethics

CUNNINGSBURGH. 1) IRO - 2a) EHTECONMORS - 2b)

DOVHDDRS - 3a) ETTECA - 3b) VDATTVB 3c) RTT Guiter: Basque reading A few individual

words only. Jackson: (1): 12 3x440 5x2x4 Nyland: 1: IRO (on stone slab) iro iro irol

privy, outhouse

2a: EHTEKONMORS eh. ehu ehun

hundreds

2b: DOBHDDRS do do doatsutasun happiness

3a: ETTEKA et.

eti

etikoa

ethical

3b: BDATTBB .b.

abe

abegitasun

fondness of

3c: RTT This last

inscription has no identifiable vowel and therefore is not translatable with

the vowel-interlocking method. POOL. RVMVORC Guiter: Basque reading: None. Jackson: 23 prime 75 5x5x3 Nyland: Pool: RBMBORK .r. ara arraro

strange, odd

GURNESS. NEITTEMTOS M0CS Guiter: Basque reading: None. Jackson: 50 5x10 189 7x3x3x3 Nyland: NEITTEMTOSMOKS. .ne ene enekin with me

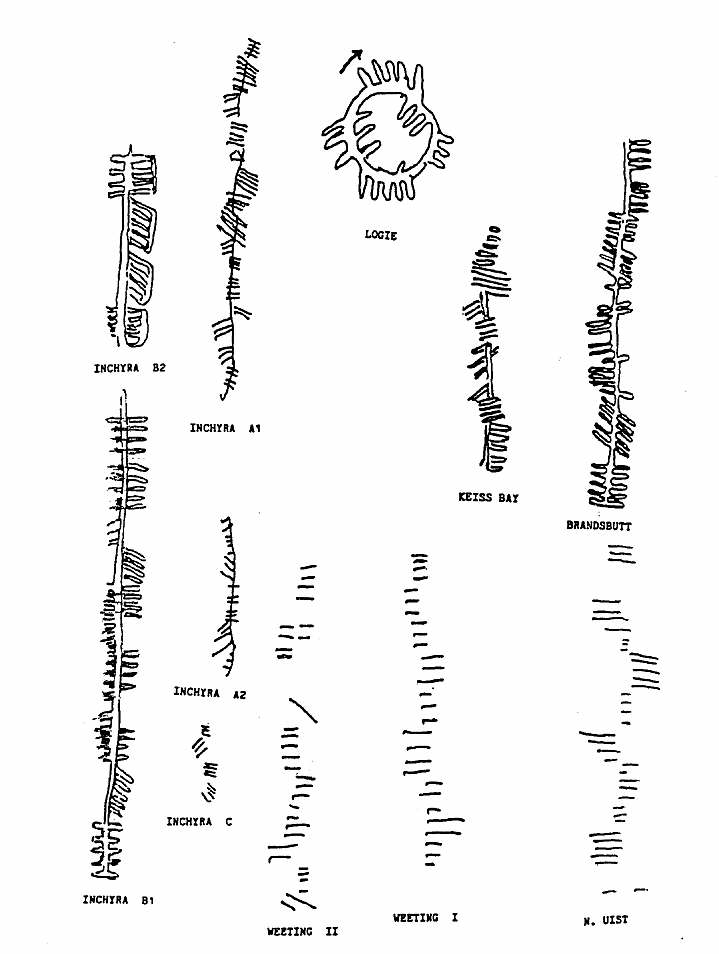

NORTH UIST. H QUNCENTC T Guiter: Basque

reading: Belaskuanuk..ta

Jackson: 37 prime 119 7x17 Nyland: HKUNKENTKT .h. ohi ohitu to get

used to

WEETING. 1) VLVEVVUTE - 2) GEDEVIM DOS Guiter: Basque reading: None. Jackson: 1) 28 7x4 84 7x3x2x2 Nyland: Weeting 1: Jackson: BLBEBBUTE,

Nyland: BLBEBBETE .b. aba abagadune occasion

Weeting 2: GEDEBIMDOS .ge age agerpen

revelation

BRANDSBUTT 8/45. IRATADDOARENS Guiter: Basque

reading: Iratakoaren.

Jackson: 40 5x8 123 3x41 Nyland: IRATADDOARENS (two possible

translations) ira ira irakatsi to preach a sermon

Nyland: IRATADDOARENS

INCHYRA - A1: OOTTLIETRENOIDDORS

Guiter: Basque

reading: Etorkoaren ...holoi...ina otsa utz

diet dinua?

Jackson: A1) 60 5x12 225 5x5x5x3 Nyland: A1: OOTTLIETRENOIDDORS o.o oho ohoregabe dishonored

A2: UHTUOAGED uh. uhe uherdura

confusion

B1: INEHHETESTIE. ine ine inertzia passive,

downtrodden

B2: INNE – in.

ine

inertzia

passive, downtrodden

C: SETU .se ase asetu

to be filled with

KEISS 41/7: NEHTETRI Guiter: Basque

reading: Nauke tagona.

Jackson: 30 5x6 95 5x19 Nyland: NEHTETRI ne

ne negarreztatu grieving

LOGIE

8/5: CALTQU

Guiter: Basque

reading: Kalkakoa

Jackson: 18 6x3 70 5x2x7 Nyland: KALTKU .ka

aka akabu

death

ABOYNE A: NEHHTVROBBACC – ENNEVV ABOYNE B: MAQQOTALLUORR Guiter: Basque

reading: Lemako da lurrpe. Dator doaken enea.

Jackson: A) 59 prime 149 prime Nyland: A) NEHHTBROBBAKK – ENNEBB .ne ene enetan

always

en. ene enetan

always

B: MAKKOTALLUORR. .ma ama ama

mother

BRODIE A 31/5: VONECCO BRODIE B 31/5: RAMINNGCHQODTOSLMBS BRODIE C 31/5: EDDARRNONR TTI Guiter: Basque reading: Idarreko noa doa mokorra erala behar aikaz bedi.Du sutu ocean iasoa lurreko karrak. Ba lo elhurra-be dago, haike,

aikako ibaia du.

Jackson: A) 24 8x3 58 29x2 Nyland: A: BONEKKO. .bo abo aboskatu to

express

B: RAMINNGKHKODTOSLMBS. This fairly long

inscription is a complicated puzzle, which has not yet yielded its secret,

probably because of the difficulties with reading the eroded inscription. C: EDDARRNONR TTI ed. eda edan

to drink

GOLSPIE 17/31: ALLHHALLORREDDMEOO – NUUVALHNRERR Guiter: Basque

reading: Aldalurrekoak hartza lotu zuan.

Jackson: 88 8x11 320 5x8x8 Nyland: This large

inscription looks authentic and should have given up its secrets, but I

didn’t succeed yet in decoding it. LATHERON 40E/41: DUVNODNNATMAOONAHATO Guiter: Basque

reading: Doana da Eneko t’ekaitsua

Jackson: 56 8x7 208 13x4x4 Nyland: DUBNODNNATMAOONAHATO .du edu eduki

to have

SCOONIE -/31: EDDARRNOSN Guiter: Basque

reading: udara zan onsa.

Jackson: 35 5x7 106 53x2 Nyland: EDDARRNOSN ed. ede eder egin to give

pleasure

ALTYRE: AMMAQQHTALLMVBVMAA-HHRRASSUDDS Guiter: Basque reading: None. Jackson: 66 11x6 281 prime Nyland: AMMAKKHTALLMBBBMAAHHRRASSUDDS am. ama ama

mother

ABERNETHY: QMI. Guiter: Basque reading: None. Jackson: 11 prime 37 prime Nyland: KMI .k. ika

ikara fears

This is the first translation that appeared. KMI is very short,

doesn’t leave much to work with, and cannot be translated with certainty. AUQUHOLLIE: VUUNON - TEDOV – BB Guiter: Basque

reading: Hila du ileko obiak.

Jackson: 37 prime 138 6x23 Nyland: VUUNON. The

transliteration of this inscription is a problem. Only part makes

sense, the VCV "uno" does not exist and "BB" has no

vowel. (TEDOV) should read: TSOLV .te ate atedanbada knock on the

door

NEWTON: Jackson: A:

IDDARQNNNVORRENNIEUA B: IOSRE

Guiter: Basque

reading: Idarkoari hor Eneko dio zagor.

Jackson: A) 77 7x11 210 7x3x10 Nyland: A: IEARKNNNBDRRENNIEUA i.e ihe ihesleku find

shelter

NEWTON B: IOSRZ i.o iho ihortziri thunder

DUNADD A: AESD - T - V

- LVA – TV DUNADD B: L---VIRRAMDNA Guiter: Basque reading: None. Jackson: A) 29 prime 96 4x4x6 Nyland: A: AESD - T - B - TB. This inscription is too fractured to do

anything with it. B: L — BIRRAMDNAI L ? lagun?

friends?

CILLE BARRA STONE TIRTHURKIRTHUS;INRRISKURSSIARISTA:A This stone was

removed in 1865 from the Cille Barra cemetary (Isle of Barra) and taken to

the Museum of Antiquities in Edinburgh. It was always thought to be a

gravestone, which it obviously is not. The transliteration was copied from a

local tourist pamphlet. The twin islands Barra-Vatersay are the most

southerly populated islands in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. The inscription

is not found in Jackson’s or Guiter’s writings. TIRTHURKIRTHUS .ti uti utikan! get away

from here!

INRRISKURSSIARISTA:A in. ino inor

everyone Everyone is dismayed,

petrified and overwhelmed to be eye-witness to this shocking flood from the

beginning; to dry up we escaped to this leaky shelter. It must be

pointed out that these are not Pictish Ogams; instead, they are Irish Ogams in Pictland

because they were written by early Irish evangelists who came to Scotland to

convert the Pictish "heathens" to the Irish form of Christianity.

All of the Irish and Scottish Ogam inscriptions that Edo Nyland has translated,

and he has done almost one hundred, are written in the Basque language,

without exception. Many, if not most, geographical and family names of

Ireland and Scotland can also be translated with the Basque dictionary using

the technique demonstrated above. Considering the evidence, it appears

certain that prior to the coming of Roman Catholicism in about 650 A.D., the

Basque language, or an earlier form of it, was spoken as the popular language

of the islands. This language was generally referred to by continental

evangelists as the "Iron

Language", also called Pictish in Scotland

and Cruithin in Ireland. It seems to indicate that the

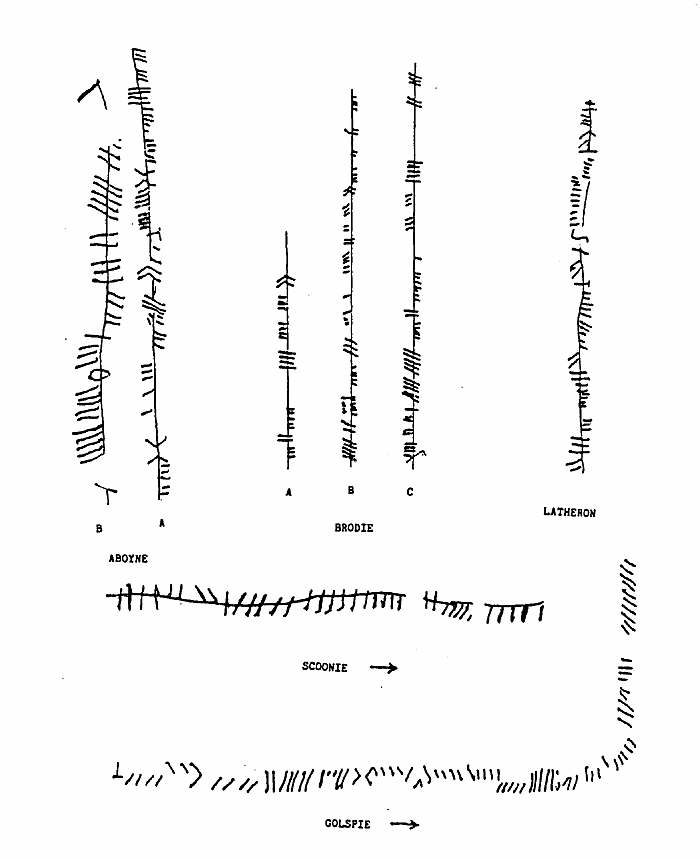

Basque language hasn’t changed much over the past 1,500 years. Figure 1 Reprinted by permission from Anthony Jackson, ‘Pictish Symbol

Stones ?’ 1993

Figure 2 Reprinted by permission from Anthony Jackson, ‘Pictish Symbol

Stones ?’ 1993

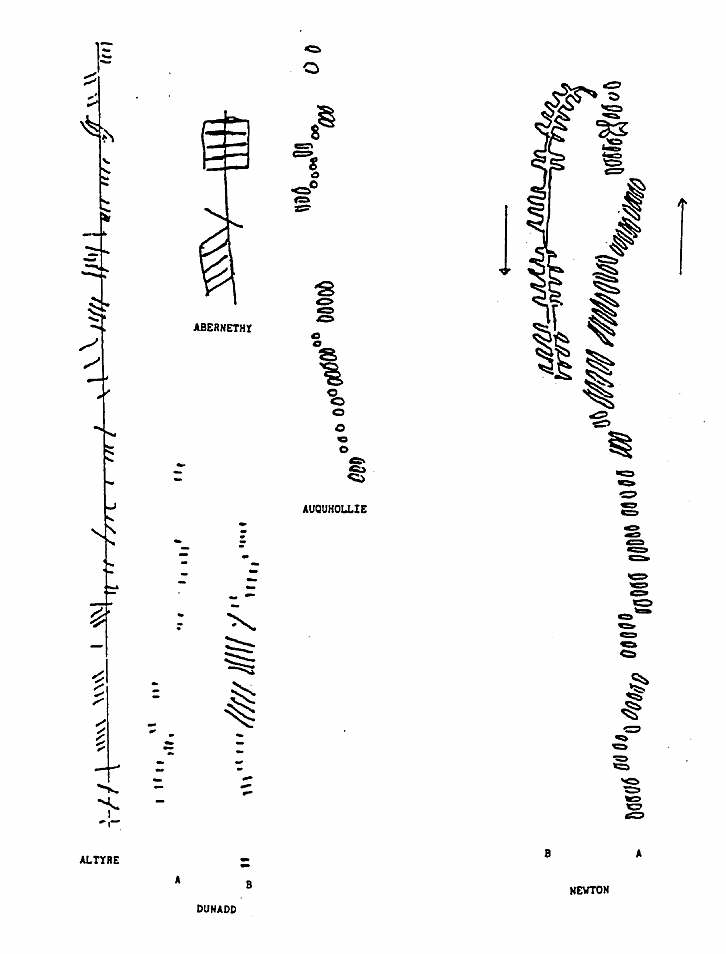

Figure 3. Reprinted by permission from Anthony Jackson, ‘Pictish Symbol

Stones ?’ 1993

Figure 4 Reprinted by permission from Anthony Jackson, ‘Pictish Symbol

Stones ?’ 1993

Figure 5. Reprinted by permission from Anthony Jackson, ‘Pictish Symbol

Stones ?’ 1993

|