File: <Adam Arkfeld.htm> Citations Dedications General

Index Subject Index <Home>

|

PRE-COLUMBIAN

VIRGINIA ARCHEOLOGICAL SITE Adam Arkfeld adam.arkfeld@gmail.com Please CLICK on Underlined Categories for details and Photos to enlarge.

Depress Ctrl/F for subject search. Investigations of an

archaeological site along the Opequon

Creek in the Northern

Shenandoah Valley of Virginia since 2012 points to the presence of

ancient Scythian colonists.

Significant amounts of iron slag and refractories are present. (see Radiocarbon Report #1 &

#2). Also

recovered are cast iron artifacts (Fig. ?).

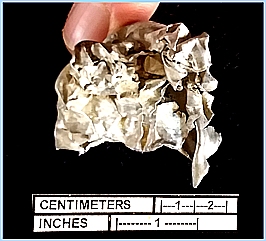

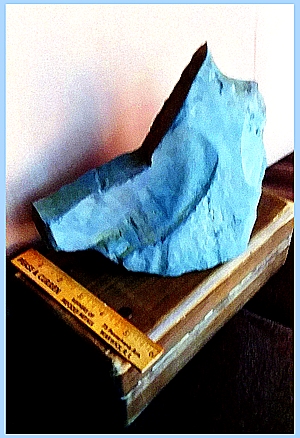

The metallurgy here was quite advanced. As unlikely as it seems, slags found suggest aluminum

production. One at first is very

skeptical, as it seems far too advanced for the time period. However, then there was the discovery of a

piece of aircraft aluminum that has been sculpted into a profile (Fig. ?

). (Enki perhaps). It was recovered at a depth in association

with stone artifacts. Another large

piece has been recovered since (Fig. ?).

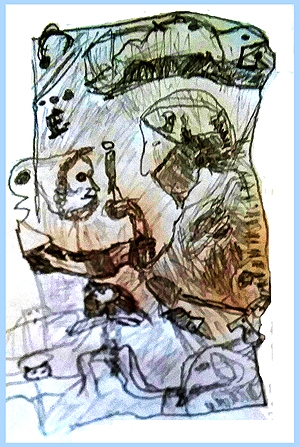

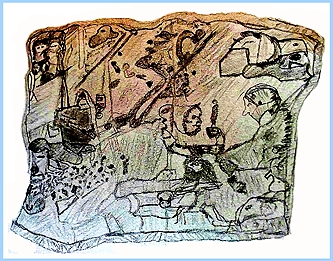

See vimana craft with tail rudder on upper right (Fig. ???). Impossibly small pilot at controls. Very mysterious. An

advanced blast furnace was operating in the area circa 150 AD. (Fig. 19) Remnants of the milldam and deep race

channels are readily observable (Fig. ?).

C14 results bracket the TL date ??.

Not only was evidence uncovered of advanced metallurgy but also fired brick

was manufactured in great quantities during the same period (Fig. ?). TL results

from the brick are in process of determination. Evidence indicates that a step mound was faced with glazed

brick pavers (Fig. ?). There are

virtually tons of 2000-year-old brick in

situ. (Fig. ?). The

furnace wall sample was dated 150 AD by the University of Washington. There is proof that smelting was occurring

here on an industrial scale using an anthracite fired blast furnace. Sections of the milldam are still existent.

Significant earth works created to channel the millrace are still apparent. Anthracite has been found in association

with the furnace. C14 testing of the slag confirms fossil fuel use. Two different samples tested by Beta Labs,

both produced infinite dates.

Anthracite is the only coal suitable for smelting. Geological maps show that east coast

anthracite beds accessible by water are limited. The most accessible mine from the Chesapeake is the Meadow

Branch Mine in West Virginia, and 20 miles west of the furnace site. The archeological site is the closest one

can get to the mine where a mill could be constructed and there is a

navigable water route to the Potomac River. The fuel was crucial to their metallurgy,

which would explain why this location was chosen. A two pound pig bar is

shown on the cover of Fig. 19.

Most recognize thie limestone

sculpture in Figure 7

as an Anubis bust. On learning that

it is from Virginia, an observer's vision becomes fuzzy and denial sets

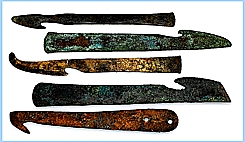

in. The iron-embalming knives (Fig.

9) cause a similar reaction. I

have fired clay and stone Horus hawks, Osiris, Thoth...pretty much the whole

pantheon. Many Baal figurines (Fig.

?) and his signature pornography (Fig. ?)

as well. There is no lack of

Scythian characters, tall pointed hats abound (Fig. ?). The stone mounds here are interlaced with

logs, consistent with Kurgan design. The Sumerians were probably the only

culture with knowledge to make an accurate planetary chart (Fig. 13). This example was recovered adjacent to a stream in an aqueous

environment. The etched circles on

the back of a Taurus (or bison) bull (Fig. 12) have been permeated with white calcite.

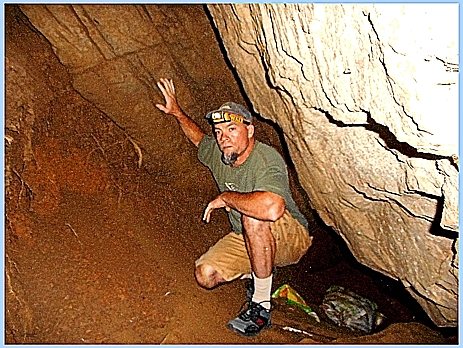

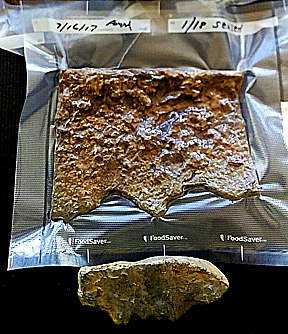

This mattock was recovered within

10 feet of the cast iron profile.

Both of these artifacts were submerged and preserved in mud and sand.

The water has a high mineral concentration.

I have sealed both because exposure began deteriorating them rapidly.

The wood remaining in the socket of the mattock is petrified. I have little doubt of the antiquity of

the iron mask as the profile matches many others in my collection that are

made of stone. The mattock is made of the same metal and shows identical

patination/oxidation. It can be

surmised that both items are from the same time period. Assuming that organic material is still

present, the wood remaining in the socket makes that mattock an ideal iron

artifact to test and date. the Opequon Creek = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

= = = = = = = = = Wilson, Charles A. and A. A.

Field. 2017. The Arkfeld site Iron Smelting Virginia 150 AD.: Discoveries

Along the Opequon Creek. Ancient American.

2017. Archeology of The

Americas Before Columbus. Vol. 21

(114). Anthony,

David W. (July 26, 2010). The Horse,

the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes

Shaped the Modern World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 1-4008-3110-5.

Retrieved January 18, 2015. Baumer,

Christoph (December 12, 2012). The

History of Central Asia: The Age of the Steppe Warriors. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 1-78076-060-4.

Retrieved January 18, 2015. Beckwith, Christopher I. (March 16, 2009). Empires of

the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the

Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 1-4008-2994-1.

Retrieved December 30, 2014. Bertman, S.

(2014). Handbook to Life in Ancient

Mesopotamia. Oxford Univ. Press. Boardman, John; Edwards,

I. E. S. (1991). The

Cambridge Ancient History. Volume 3. Part 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22717-8.

Retrieved March 2, 2015. Bonfante,

Larissa (2011). "The Scythians: Between Mobility, Tomb Architecture, and

Early Urban Structures". The Barbarians of Ancient Europe: Realities and Interactions. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19404-4. Davis-Kimball,

Jeannine (1995). "The Scythians in southeastern Europe". Nomads of the Eurasian Steppes in the early Iron Age (PDF). Zinat press. ISBN 1-885979-00-2. Day,

John V. (2001). Indo-European

origins: the anthropological evidence. Institute for the Study of Man. ISBN 0-941694-75-5.

Retrieved March 2, 2015. Drews,

Robert (2004). Early Riders: The Beginnings of Mounted Warfare in Asia and

Europe. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-07107-6. Durant, W.

1954. (1954). Our Oriental Heritage. Simon & Schuster Publ. 1052 pp. Ivantchik,

Askold (2018). "SCYTHIANS". Encyclopaedia

Iranica. Kramer, S. N. (1971). The Sumerians. Univ. of

Chicago Press. 372 pp. Kramer, S. N.

(1988). History Begins at

Sumer. Univ. of Pennsylvania

Press. 416 pp. Kriwaczek, P. (2014). Babylon. Thomas Dunne

Books. Leick, G.

(2010). The A to Z of

Mesopotamia. Scarecrow Press. Podany, A. H.

(2013). The Ancient Near

East. Oxford Univ. Press. 168 pp. Sinor,

Denis (1990). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia. Cambridge. ISBN 978-0-521-24304-9. Sulimirski,

T (1985). "Chapter 4: The Scyths". In Gershevitch, Ilya. The

Cambridge History of Iran. 2.

Azargoshnasp.net. pp. 149–99 Szemerényi, Oswald (1980). Four old Iranian ethnic names: Scythian – Skudra – Sogdian –

Saka (PDF). Veröffentlichungen der iranischen Kommission Band 9.

Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften;

azargoshnap.net. Waldman,

Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia

of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 1-4381-2918-1.

Retrieved January 16, 2015. West, Barbara A. (January

1, 2009). Encyclopedia

of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 1-4381-1913-5.

Retrieved January 18, 2015. |