Jerks, Zombie Robots, and Other Philosophical Misadventures

Eric Schwitzgebel

in memory of my father,

psychologist, inventor,

parent, philosopher, and giver of strange objects

Preface

I enjoy writing short philosophical reflections for

broad audiences. Evidently, I enjoy this

a lot: Since 2006, I’ve written over a thousand such pieces, mostly published

on my blog The Splintered Mind, but

also in the Los Angeles Times, Aeon

Magazine, and elsewhere. This book

contains fifty-eight of my favorites, revised and updated.

The topics range widely, as I’ve tried to capture in

the title of the book. I discuss moral

psychology (“jerks”), speculative philosophy of consciousness (“zombie robots”),

the risks of controlling your emotions technologically, the ethics of the game

of dreidel, multiverse theory, the apparent foolishness of Immanuel Kant, and

much else. There is no unifying topic.

Maybe, however, there is a unifying theme. The human intellect has a ragged edge, where

it begins to turn against itself, casting doubt on itself or finding itself

lost among seemingly improbable conclusions.

We can reach this ragged edge quickly.

Sometimes, all it takes to remind us of our limits is an eight-hundred-word

blog post. Playing at this ragged edge,

where I no longer know quite what to think or how to think about it, is my idea

of fun.

Given the human propensity for rationalization and

self-deception, when I disapprove of others, how do I know that I’m not the one

who is being a jerk? Given that all our

intuitive, philosophical, and scientific knowledge of the mind has been built

on a narrow range of cases, how much confidence can we have in our conclusions

about strange new possibilities that are likely to open up in the near future

of Artificial Intelligence? Speculative

cosmology at once poses the (literally) biggest questions that we can ask about

the universe while opening up possibilities that undermine our confidence in

our ability to answer those same questions.

The history of philosophy is humbling when we see how badly wrong

previous thinkers have been, despite their intellectual skills and confidence.

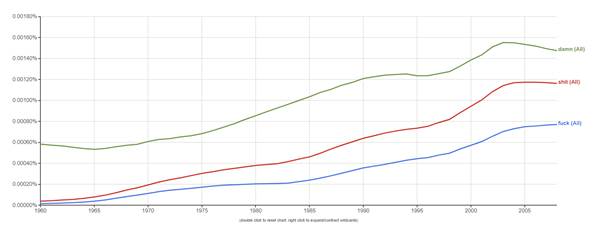

Not all of my posts fit this theme. It’s also fun to use the once-forbidden word

“fuck” over and over again in a chapter about profanity. And I wanted to share some reminiscences about

how my father saw the world – especially since in some ways I prefer his

optimistic and proactive vision to my own less hopeful skepticism. Other of my blog posts I just liked or wanted

to share for other reasons. A few are

short fictions.

It would be an unusual reader who liked every

chapter. I hope you’ll skip anything you

find boring. The chapters are all

free-standing. Please don’t just start

reading on page one and then try to slog along through everything sequentially

out of some misplaced sense of duty!

Trust your sense of fun (Chapter 47).

Read only the chapters that appeal to you, in any order you like.

Riverside, California, Earth (I hope)

October 25, 2018

Part One: Jerks and Excuses

1.

A Theory of Jerks

2.

Forgetting as an Unwitting Confession of Your Values

3.

The Happy Coincidence Defense and The-Most-You-Can-Do Sweet Spot

4. Cheeseburger

Ethics (or How Often Do Ethicists Call Their Mothers?)

5.

On Not Seeking Pleasure Much

6.

How Much Should You Care about How You Feel in Your Dreams?

7.

Imagining Yourself in Another’s Shoes vs. Extending Your Love

8. Is

It Perfectly Fine to Aim for Moral Mediocrity?

9.

A Theory of Hypocrisy

10.

On Not Distinguishing Too Finely Among Your Motivations

11.

The Mush of Normativity

12.

A Moral Dunning-Kruger Effect?

13.

The Moral Compass and the Liberal Ideal in Moral Education

Part Two: Cute AI and Zombie Robots

14.

Should Your Driverless Car Kill You So Others May Live?

15.

Cute AI and the ASIMO Problem

16.

My Daughter’s Rented Eyes

17.

Someday, Your Employer Will Technologically Control Your Moods

18.

Cheerfully Suicidal AI Slaves

19.

We Would Have Greater Moral Obligations to Conscious Robots Than to Otherwise

Similar Humans

20.

How Robots and Monsters Might Destroy Human Moral Systems

21.

Our Possible Imminent Divinity

22.

Skepticism, Godzilla, and the Artificial Computerized Many-Branching You

23.

How to Accidentally Become a Zombie Robot

Part Three: Regrets and Birthday Cake

24.

Dreidel: A Seemingly Foolish Game That Contains the Moral World in Miniature

25.

Does It Matter If the Passover Story Is Literally True?

26.

Memories of My Father

27.

Flying Free of the Deathbed, with Technological Help

28.

Thoughts on Conjugal Love

29.

Knowing What You Love

30.

The Epistemic Status of Deathbed Regrets

31.

Competing Perspectives on One’s Final, Dying Thought

32.

Profanity Inflation, Profanity Migration, and the Paradox of Prohibition (or I

Love You, “Fuck”)

33.

The Legend of the Leaning Behaviorist

34.

What Happens to Democracy When the Experts Can’t Be Both Factual and Balanced?

35.

On the Morality of Hypotenuse Walking

36.

Birthday Cake and a Chapel

Part Four: Cosmic Freaks

37.

Possible Psychology of a Matrioshka Brain

38.

A Two-Seater Homunculus

39.

Is the United States Literally Conscious?

40.

Might You Be a Cosmic Freak?

41.

Choosing to Be That Fellow Back Then: Voluntarism about Personal Identity

42.

How Everything You Do Might Have Huge Cosmic Significance

43.

Penelope’s Guide to Defeating Time, Space, and Causation

44.

Goldfish-Pool Immortality

45.

Are Garden Snails Conscious? Yes, No, or

*Gong*

Part Five: Kant vs. the Philosopher of Hair

46.

Truth, Dare, and Wonder

47.

Trusting Your Sense of Fun

48.

What’s in People’s Stream of Experience During Philosophy Talks?

49.

Why Metaphysics Is Always Bizarre

50.

The Philosopher of Hair

51.

Obfuscatory Philosophy as Intellectual Authoritarianism and Cowardice

52.

Kant on Killing Bastards, Masturbation, Organ Donation, Homosexuality, Tyrants,

Wives, and Servants

53.

Nazi Philosophers, World War I, and the Grand Wisdom Hypothesis

54.

Against Charity in the History of Philosophy

55.

Invisible Revisions

56.

On Being Good at Seeming Smart

57.

Blogging and Philosophical Cognition

58.

Will Future Generations Find Us Morally Loathsome?

Part One: Jerks and Excuses

1. A Theory of Jerks

Picture the world through the eyes of

the jerk. The line of people in the post

office is a mass of unimportant fools; it’s a felt injustice that you must wait

while they bumble with their requests.

The flight attendant is not a potentially interesting person with her

own cares and struggles but instead the most available face of a corporation

that stupidly insists you stow your laptop.

Custodians and secretaries are lazy complainers who rightly get the scut

work. The person who disagrees with you

at the staff meeting is an idiot to be shot down. Entering a subway is an exercise in nudging

past the dumb schmoes.

We need a theory of jerks. We need such a theory because, first, it can

help us achieve a calm, clinical understanding when confronting such a creature

in the wild. Imagine the

nature-documentary voice-over: “Here we see the jerk in his natural

environment. Notice how he subtly

adjusts his dominance display to the Italian-restaurant situation….” And second – well, I don’t want to say what

the second reason is quite yet.

As it happens, I do have such a

theory. But before we get into it, I

should clarify some terminology. The

word “jerk” can refer to two different types of person. The older use of “jerk” designates a chump or

ignorant fool, though not a morally odious one.

When Weird Al Yankovic sang, in 2006, “I sued Fruit of the Loom ’cause

when I wear their tightie-whities on my head I look like a jerk” or when, in

1959, Willard Temple wrote in the Los

Angeles Times “He could have married the campus queen…. Instead the poor jerk fell for a snub-nosed,

skinny little broad”, it’s clear it’s the chump they have in mind.[1]

The jerk-as-fool usage seems to have

begun among traveling performers as a derisive reference to the unsophisticated

people of a “jerkwater town”, that is, a town not rating a full-scale train

station, requiring the boilerman to pull on a chain to water his engine. The term expresses the traveling troupe’s

disdain.[2] Over time, however, “jerk” shifted from being

primarily a class-based insult to its second, now dominant, sense as a moral

condemnation. Such linguistic drift from

class-based contempt to moral deprecation is a common pattern across languages,

as observed by Friedrich Nietzsche in On

the Genealogy of Morality.[3] (In English, consider “rude”, “villain”, and

“ignoble”.) It is the immoral jerk who

concerns me here.

Why, you might be wondering, should a

philosopher make it his business to analyze colloquial terms of abuse? Doesn’t the Urban Dictionary cover that kind

of thing quite adequately? Shouldn’t I

confine myself to truth, or beauty, or knowledge, or why there is something

rather than nothing? I am, in fact,

interested in all those topics. And yet

I see a folk wisdom in the term “jerk” that points toward something morally

important. I want to extract that

morally important thing, isolating the core phenomenon implicit in our

usage. Precedents for this type of

philosophical work include Harry Frankfurt’s essay On Bullshit and, closer to my target, Aaron James’s book Assholes.[4] Our taste in vulgarity reveals our values.

I submit that the unifying core, the

essence of jerkitude in the moral sense, is this: The jerk culpably fails to appreciate the perspectives of others around

him, treating them as tools to be manipulated or fools to be dealt with rather

than as moral and epistemic peers.

This failure has both an intellectual dimension and an emotional

dimension, and it has these two dimensions on both sides of the

relationship. The jerk himself is both

intellectually and emotionally defective, and what he defectively fails to

appreciate is both the intellectual and emotional perspectives of the people

around him. He can’t appreciate how he

might be wrong and others right about some matter of fact; and what other

people want or value doesn’t register as of interest to him, except

derivatively upon his own interests. The

bumpkin ignorance captured in the earlier use of “jerk” has become a type of

moral ignorance.

Some related traits are already

well-known in psychology and philosophy – the “dark triad” of Machiavellianism,

narcissism, and psychopathy; low “Agreeableness” on the Big Five personality

test; and Aaron James’s conception of the asshole, already mentioned. But my conception of the jerk differs from

all of these. The asshole, James says,

is someone who allows himself to enjoy special advantages out of an entrenched

sense of entitlement.[5] That is one important dimension of jerkitude,

but not the whole story. The callous

psychopath, though cousin to the jerk, has an impulsivity and love of

risk-taking that needn’t belong to the jerk’s character.[6] Neither does the jerk have to be as

thoroughly self-involved as the narcissist or as self-consciously cynical as

the Machiavellian, though narcissism and Machiavellianism are common jerkish

attributes.[7] People low in Big-5 Agreeableness tend to be

unhelpful, mistrusting, and difficult to get along with – again, features

related to jerkitude, and perhaps even partly constitutive of it, but not exactly

jerkitude as I’ve defined it. Also, my definition

of jerkitude has a conceptual unity that is, I think, theoretically appealing

in the abstract and fruitful in helping to explain some of the peculiar

features of this type of animal, as we will see.

The opposite of the jerk is the sweetheart. The sweetheart sees others around him, even

strangers, as individually distinctive people with valuable perspectives, whose

desires and opinions, interests and goals, are worthy of attention and respect. The sweetheart yields his place in line to

the hurried shopper, stops to help the person who has dropped her papers, calls

an acquaintance with an embarrassed apology after having been unintentionally

rude. In a debate, the sweetheart sees

how he might be wrong and the other person right.

The moral and emotional failure of the

jerk is obvious. The intellectual

failure is obvious, too: No one is as right about everything as the jerk thinks

he is. He would learn by listening. And one of the things he might learn is the

true scope of his jerkitude – a fact about which, as I will explain shortly,

the all-out jerk is inevitably ignorant.

This brings me to the other great benefit of a theory of jerks: It might

help you figure out if you yourself are one.

#

Some clarifications and caveats.

First, no one is a perfect jerk or a

perfect sweetheart. Human behavior – of

course! – various hugely with context.

Different situations (department meetings, traveling in close quarters)

might bring out the jerk in some and the sweetie in others.

Second, the jerk is someone who culpably fails to appreciate the

perspectives of others around him. Young

children and people with severe cognitive disabilities aren’t capable of

appreciating others’ perspectives, so they can’t be blamed for their failure

and aren’t jerks. (“What a selfish

jerk!” you say about the baby next to you on the bus, who is hollering and

flinging her slobbery toy around. Of

course you mean it only as a joke.

Hopefully.) Also, not all

perspectives deserve equal treatment. Failure to appreciate the outlook of a

neo-Nazi, for example, is not a sign of jerkitude – though the true sweetheart

might bend over backwards to try.

Third, I’ve called the jerk “he”, since

the best stereotypical examples of jerks tend to be male, for some reason. But then it seems too gendered to call the

sweetheart “she”, so I’ve made the sweetheart a “he” too.

#

I’ve said that my theory might help us

assess whether we, ourselves, are jerks.

In fact, this turns out to be a strangely difficult question. The psychologist Simine Vazire has argued

that we tend to know our own personality traits rather well when the traits are

evaluatively neutral and straightforwardly observable, and badly when the

traits are highly value-laden and not straightforward to observe.[8] If you ask people how talkative they are, or

whether they are relatively high-strung or mellow, and then you ask their

friends to rate them along those same dimensions, the self-ratings and the peer

ratings usually correlate well – and both sets of ratings also tend to line up

with psychologists’ attempts to measure such traits objectively.

Why?

Presumably because it’s more or less fine to be talkative and more or

less fine to be quiet; okay to be a bouncing bunny and okay instead to keep it

low-key, and such traits are hard to miss in any case. But few of us want to be inflexible, stupid,

unfair, or low in creativity. And if you

don’t want to see yourself that way, it’s easy enough to dismiss the

signs. Such characteristics are, after

all, connected to outward behavior in somewhat complicated ways; we can always

cling to the idea that we’ve been misunderstood by those who charge us with

such defects. Thus, we overlook our

faults.

With Vazire’s model of self-knowledge in

mind, I conjecture a correlation of approximately zero between how one would

rate oneself in relative jerkitude and one’s actual true jerkitude. The term is morally loaded, and

rationalization is so tempting and easy!

Why did you just treat that cashier so harshly? Well, she deserved it – and anyway, I’ve been

having a rough day. Why did you just cut

into that line of cars at the last moment, not waiting your turn to exit? Well, that’s just good tactical driving – and

anyway, I’m in a hurry! Why did you seem

to relish failing that student for submitting his essay an hour late? Well, the rules were clearly stated; it’s

only fair to the students who worked hard to submit their essays on time – and

that was a grimace not a smile.

Since probably the most effective way to

learn about defects in one’s character is to listen to frank feedback from

people whose opinions you respect, the jerk faces special obstacles on the road

to self-knowledge, beyond even what Vazire’s theory would lead us to

expect. By definition, he fails to

respect the perspectives of others around him.

He’s much more likely to dismiss critics as fools – or as jerks themselves

– than to take the criticism to heart.

Still, it’s entirely possible for a

picture-perfect jerk to acknowledge, in a superficial

way, that he is a jerk. “So what, yeah,

I’m a jerk,” he might say. Provided that

this admission carries no real sting of self-disapprobation, the jerk’s moral

self-ignorance remains. Part of what it

is to fail to appreciate the perspectives of others is to fail to see what’s

inappropriate in your jerkishly dismissive attitude toward their ideas and

concerns.

Ironically, it is the sweetheart who

worries that he has just behaved inappropriately, that he might have acted too

jerkishly, and who feels driven to make amends.

Such distress is impossible if you don’t take others’ perspectives

seriously into account. Indeed, the

distress itself constitutes a deviation (in this one respect at least) from

pure jerkitude: Worrying about whether it might be so helps to make it less

so. Then again, if you take comfort in

that fact and cease worrying, you have undermined the very basis of your

comfort.

#

Jerks normally distribute their

jerkitude mostly down the social

hierarchy, and to anonymous strangers.

Waitresses, students, clerks, strangers on the road – these are the

unfortunate people who bear the brunt of it.

With a modicum of self-control, the jerk, though he implicitly or

explicitly regards himself as more important than most of the people around

him, recognizes that the perspectives of others above him in the hierarchy also

deserve some consideration. Often,

indeed, he feels sincere respect for his higher-ups. Maybe deferential impulses are too deeply

written in our natures to disappear entirely.

Maybe the jerk retains a vestigial concern specifically for those he

would benefit, directly or indirectly, from winning over. He is at least concerned enough about their

opinion of him to display tactical respect while in their field of view. However it comes about, the classic jerk

kisses up and kicks down. For this

reason, the company CEO rarely knows who the jerks are, though it’s no great

mystery among the secretaries.

Because the jerk tends to disregard the

perspectives of those below him in the hierarchy, he often has little idea how

he appears to them. This can lead to ironies

and hypocrisy. He might rage against the

smallest typo in a student’s or secretary’s document, while producing a torrent

of typos himself; it just wouldn’t occur to him to apply the same standards to

himself. He might insist on promptness,

while always running late. He might

freely reprimand other people, expecting them to take it with good grace, while

any complaints directed against him earn his undying enmity. Such failures of parity typify the jerk’s

moral short-sightedness, flowing naturally from his disregard of others’

perspectives. These hypocrisies are

immediately obvious if one genuinely imagines oneself in a subordinate’s shoes

for anything other than selfish and self-rationalizing ends, but this is

exactly what the jerk habitually fails to do.

Embarrassment, too, becomes practically

impossible for the jerk, at least in front of his underlings. Embarrassment requires us to imagine being

viewed negatively by people whose perspectives we care about. As the circle of people the jerk is willing

to regard as true peers and superiors shrinks, so does his capacity for shame –

and with it a crucial entry point for moral self-knowledge.

As one climbs the social hierarchy it is

also easier to become a jerk. Here’s a characteristically jerkish thought:

“I’m important and I’m surrounded by idiots!”

Both halves of this proposition serve to conceal the jerk’s jerkitude

from himself. Thinking yourself

important is a pleasantly self-gratifying excuse for disregarding the interests

and desires of others. Thinking that the

people around you are idiots seems like a good reason to dismiss their

intellectual perspectives. As you ascend

the social hierarchy, you will find it easier to discover evidence of your

relative importance (your big salary, your first-class seat) and of the

relative stupidity of others (who have failed to ascend as high as you). Also, flatterers will tend to squeeze out

frank, authentic critics.

This isn’t the only possible explanation

for the prevalence of powerful jerks.

Maybe natural, intuitive jerks are also more likely to rise in

government, business, and academia than non-jerks. The truest sweethearts often suffer from an

inability to advance their own projects over the projects of others. But I suspect the causal path runs at least

as much the other direction. Success

might or might not favor the existing jerks, but I’m pretty sure it nurtures

new ones.

#

The moralistic

jerk is an animal worth special remark.

Charles Dickens was a master painter of the type: his teachers, his

preachers, his petty bureaucrats and self-satisfied businessmen, Scrooge

condemning the poor as lazy, Mr. Bumble shocked that Oliver Twist dares to ask

for more food, each dismissive of the opinions and desires of their social

inferiors, each inflated with a proud self-image and ignorant of how they are

rightly seen by those around them, and each rationalizing this picture with a

web of moralizing “shoulds”.

Scrooge and Bumble are cartoons, and we

can be pretty sure we aren’t as bad as them.

Yet I see in myself and all those who are not pure sweethearts a

tendency to rationalize my privilege with moralistic sham justifications. Here’s my reason for dishonestly trying to

wheedle my daughter into the best school; my reason why the session chair

should call on me rather than on the grad student who got her hand up earlier;

my reason why it’s fine that I have 400 library books in my office….

Philosophers appear to have a special

talent in concocting such dubious justifications: With enough work, we can

concoct a moral rationalization for anything!

Such skill at rationalization might partly explain why ethicist

philosophers seem to behave no morally better, on average, than do comparison

groups of non-ethicists, as my collaborators and I have found in a long series

of empirical studies on issues ranging from returning library books, to

courteous behavior at professional conferences, to rates of charitable giving,

to membership in the Nazi party in 1930s Germany (see Chapters 4 and 53). The moralistic jerk’s rationalizations

justify his disregard of others, and his disregard of others prevents him from

accepting an outside corrective on his rationalizations, in a self-insulating

cycle. Here’s why it’s fine for him, he

says, to neglect his obligations to his underlings and inflate his expense

claims, you idiot critics. Coat the

whole thing, if you like, in a patina of business-speak or academic jargon.

The moralizing jerk is apt to go badly

wrong in his moral opinions. Partly this

is because his morality tends to be self-serving, and partly it’s because his

disrespect for others’ perspectives puts him at a general epistemic

disadvantage. But there’s more to it than

that. In failing to appreciate others’

perspectives, the jerk almost inevitably fails to appreciate the full range of

human goods – the value of dancing, say, or of sports, nature, pets, local

cultural rituals, and indeed anything that he doesn’t personally care for. Think of the aggressively rumpled scholar who

can’t bear the thought that someone would waste her time getting a manicure. Or think of the manicured socialite who can’t

see the value of dedicating one’s life to dusty Latin manuscripts. Whatever he’s into, the moralizing jerk

exudes a continuous aura of disdain for everything else.

Furthermore, mercy is near the heart of practical, lived morality. Virtually everything that everyone does falls

short of perfection: one’s turn of phrase is less than perfect, one arrives a

bit late, one’s clothes are tacky, one’s gesture irritable, one’s choice

somewhat selfish, one’s coffee less than frugal, one’s melody trite. Practical mercy involves letting these

imperfections pass forgiven or, better yet, entirely unnoticed. In contrast, the jerk appreciates neither

others’ difficulties in attaining all the perfections that he attributes to

himself, nor the possibility that some portion of what he regards as flawed is

in fact blameless. Hard moralizing

principle therefore comes naturally to him.

(Sympathetic mercy is natural to the sweetheart.) And on the rare occasions where the jerk is

merciful, his indulgence is usually ill-tuned: the flaws he forgives are

exactly the ones he sees in himself or has ulterior reasons to let slide. Consider another brilliant literary cartoon

jerk: Severus Snape, the infuriating potions teacher in J.K. Rowling’s novels,

always eager to drop the hammer on Harry Potter or anyone else who happens to

annoy him, constantly bristling with indignation, but wildly off the mark –

contrasted with the mercy and broad vision of Dumbledore.

Despite the jerk’s almost inevitable

flaws in moral vision, the moralizing jerk can sometimes happen to be right

about some specific important issue (as Snape proved to be) – especially if he

adopts a big social cause. He needn’t

care only about money and prestige.

Indeed, sometimes an abstract and general concern for moral or political

principles serves as a substitute for concern about the people in his immediate

field of view, possibly leading to substantial self-sacrifice. He might loathe and mistreat everyone around

him, yet die for the cause. And in

social battles, the sweetheart will always have some disadvantages: The

sweetheart’s talent for seeing things from the opponent’s perspective deprives

him of bold self-certainty, and he is less willing to trample others for his ends. Social movements sometimes do well when led

by a moralizing jerk.

#

How can you know your own moral

character? You can try a label on for

size: “lazy”, “jerk”, “unreliable” – is that really me? As the work of Vazire and other personality

psychologists suggests, this might not be a very illuminating approach. More effective, I suspect, is to shift from

first-person reflection (what am I

like?) to second-person description (tell me, what am I like?). Instead of

introspection, try listening. Ideally,

you will have a few people in your life who know you intimately, have

integrity, and are concerned about your character. They can frankly and lovingly hold your flaws

to the light and insist that you look at them.

Give them the space to do this and prepare to be disappointed in

yourself.

Done well enough, this second-person

approach could work fairly well for traits such as laziness and unreliability,

especially if their scope is restricted – laziness-about-X,

unreliability-about-Y. But as I suggested

above, jerkitude is probably not so tractable, since if one is far enough gone,

one can’t listen in the right way. Your

critics are fools, at least on this particular topic (their critique of you). They can’t appreciate your perspective, you

think – though really it’s that you can’t appreciate theirs.

To discover one’s degree of jerkitude,

the best approach might be neither (first-person) direct reflection upon

yourself nor (second-person) conversation with intimate critics, but rather

something more third-person: looking in general at other people. Everywhere you turn, are you surrounded by

fools, by boring nonentities, by faceless masses and foes and suckers and,

indeed, jerks? Are you the only

competent, reasonable person to be found?

In other words, how familiar was the vision of the world I described at

the beginning of this essay?

If your self-rationalizing defenses are

low enough to feel a little pang of shame at the familiarity of that vision of

the world, then you probably aren’t pure diamond-grade jerk. But who is?

We’re all somewhere in the middle.

That’s what makes the jerk’s vision of the world so instantly

recognizable. It’s our own vision. But, thankfully, only sometimes.

2. Forgetting as an Unwitting Confession of Your Values

Every September 11, my social media

feeds are full of reminders to “never forget” the Twin Tower terrorist

attacks. Similarly, the Jewish community

insists that we keep vivid the memory of the Holocaust. It says something about a person’s values,

what they strive to remember – a debt, a harm, a treasured moment, a loved one

now gone, an error or lesson.

What we remember says, perhaps, more

about us than we would want.

Forgetfulness can be an unwitting confession of your values. The Nazi Adolf Eichmann, in Hannah Arendt’s

famous portrayal of him, had little memory of his decisions about shipping

thousands of Jews to their deaths, but he remembered in detail small social

triumphs with his Nazi superiors. The

transports he forgot – but how vividly he remembers the notable occasion when

he was permitted to lounge beside a fireplace with Reinhard Heydrich, watching the

Nazi leader smoke and drink![9] Eichmann’s failures and successes of memory

are more eloquent and accurate testimony of his values than any of his outward

avowals.

I remember obscure little arguments in

philosophy articles if they are relevant to an essay I’m working on, but I

can’t seem to recall the names of the parents of my children’s friends. Some of us remember insults and others forget

them. Some remember the exotic foods

they ate on vacation, others the buildings they saw, others the wildlife, and

still others hardly anything specific at all.

From the leavings of memory and

forgetting we could create a map, I think, of a person’s values. Features of the world that you don’t see –

the subtle sadness in a colleague’s face? – and features that you briefly see

but don’t react to or retain, are in some sense not part of the world shaped

for you by your interests and values.

Other people with different values will remember a very different series

of events.

To carve David, simply remove everything

from the stone that is not David.[10] Remove from your life everything you forget;

what is left is you.

3. The Happy

Coincidence Defense and The-Most-You-Can-Do Sweet Spot

Here are four things I care intensely

about: being a good father, being a good philosopher, being a good teacher, and

being a morally good person. It would be

lovely if there were never any tradeoffs among these four aims.

It is highly unpleasant to acknowledge

such tradeoffs – sufficiently unpleasant that most of us try to rationalize

them away. It’s distinctly uncomfortable

to me, for example, to acknowledge that I would probably be a better father if

I traveled less for work. (I am writing

now from a hotel room in England.)

Similarly uncomfortable is the thought that the money I will spend this

summer on a family trip to Iceland could probably save a few people from death

due to poverty-related causes, if given to the right charity.[11]

Below are two of my favorite techniques

for rationalizing such unpleasant thoughts away. Maybe you’ll find these techniques useful

too!

#

The Happy

Coincidence Defense

Consider travel for work. I don’t really need to travel around the

world giving talks and meeting people.

No one will fire me if I don’t do it, and some of my colleagues do it much

less. On the face of it, I seem to be

prioritizing my research career at the cost of being a somewhat less good

father, teacher, and global moral citizen (given the pollution of air travel

and the luxurious use of resources).

The Happy Coincidence Defense says, no,

in fact I am not sacrificing these other goals at all. Although I am away from my children, I am a

better father for it. I am a role model

of career success for them, and I can tell them stories about my travels. I have enriched my life, and I can mingle

that richness into theirs. I am a more

globally aware, wiser father! Similarly,

though I might cancel a class or two and de-prioritize lecture preparation,

since research travel improves me as a philosopher it improves my teaching in

the long run. And my philosophical work,

isn’t that an important contribution to society? Maybe it’s important enough to justify the

expense, pollution, and waste: I do more good for the world jetting around to

talk philosophy than I could do by leading a more modest lifestyle at home,

working within my own community.

After enough reflection, it can come to

seem that I’m not making any tradeoffs at all among these four things I care

intensely about. Instead I am maximizing

them all. This trip to England is the

best thing I can do, all things considered, as a philosopher and as a father and as a teacher and as a

citizen of the moral community. Yay!

Now that might be true. If so, it

would be a happy coincidence. Sometimes

there really are such happy coincidences.

We should aim to structure our lives and societies to enhance the

likelihood of such coincidences. But

still, I think you’ll agree that the pattern of reasoning is suspicious. Life is full of tradeoffs and hard choices. I’m probably just rationalizing, trying to

convince myself that something I want to be true really is true.

#

The-Most-You-Can-Do

Sweet Spot

Sometimes trying too hard at something

makes you do worse. Trying too hard to

be a good father might make you overbearing and invasive. Overpreparing a lecture can spoil your

spontaneity. And sometimes, maybe, moral

idealists push themselves so hard in support of their ideals that they collapse

along the way. For example, someone

moved by the arguments for vegetarianism who immediately attempts the very

strictest veganism might be more likely to revert to cheeseburger eating after

a few months than someone who sets their sights a bit lower.

The-Most-You-Can-Do Sweet Spot reasoning

runs like this: Whatever you’re doing right now is the most you can

realistically, sustainably do. Were I,

for example, to try any harder to be a good father, I would end up being a

worse father. Were I to spend any more

time reading and writing philosophy than I already do, I would only exhaust

myself, or I’d lose my freshness of ideas.

If I gave any more to charity, or sacrificed any more for the well-being

of others in my community, then I would… I would… I don’t know, collapse from

charity fatigue? Bristle with so much

resentment that it undercuts my good intentions?

As with Happy Coincidence reasoning,

The-Most-You-Can-Do Sweet Spot reasoning can sometimes be right. Sometimes you really are doing the most you

can do about something you care intensely about, so that if you tried to do any

more it would backfire. Sometimes you

don’t need to compromise: If you tried any harder or devoted any more time, it

really would mess things up. But it

would be amazing if this were reliably the case. I probably could be a better father, if I

spent more time with my children. I

probably could be a better teacher, if I gave more energy to my students. I probably could be a morally better person,

if I just helped others a little bit more.

If I typically think that wherever I happen to be, that’s already the

Sweet Spot, I am probably rationalizing.

#

By giving these ordinary phenomena cute

names, I hope to make them more salient and laughable. I hope to increase the chance that the next

time you or I rationalize in this way, some little voice pops up to say, in

gentle mockery, “Ah, lovely! What a

Happy Coincidence that is. You’re in the

Most-You-Can-Do Sweet Spot!” And then,

maybe, we can drop the excuse and aim for better.

4. Cheeseburger Ethics (or How

Often Do Ethicists Call Their Mothers?)

None of the classic questions of philosophy is beyond

a seven-year-old’s understanding. If God

exists, why do bad things happen? How do

you know there’s still a world on the other side of that closed door? Are we just made out of material stuff that

will turn into mud when we die? If you

could get away with robbing people just for fun, would it be reasonable to do

it? The questions are natural. It’s the answers that are hard.

In 2007, I’d just begun a series of empirical studies

on the moral behavior of professional ethicists. My son Davy, then seven years old, was in his

booster seat in the back of my car.

“What do you think, Davy?” I asked.

“People who think a lot about what’s fair and about being nice – do they

behave any better than other people? Are

they more likely to be fair? Are they

more likely to be nice?”

Davy didn’t respond right away. I caught his eye in the rearview mirror.

“The kids who always talk about being fair and

sharing,” I recall him saying, “mostly just want you to be fair to them and

share with them.”

#

When I meet an ethicist for the first time – by

“ethicist”, I mean a professor of philosophy who specializes in teaching and

researching ethics – it’s my habit to ask whether they think that ethicists

behave any differently from other types of professor. Most say no.

I’ll probe further.

Why not? Shouldn’t regularly

thinking about ethics have some sort of influence on one’s behavior? Doesn’t it seem that it would?

To my surprise, few professional ethicists seem to

have given the question much thought.

They’ll toss out responses that strike me as flip or as easily rebutted,

and then they’ll have little to add when asked to clarify. They’ll say that academic ethics is all about

abstract problems and bizarre puzzle cases, with no bearing on day-to-day life

– a claim easily shown to be false by a few examples: Aristotle on virtue, Kant

on lying, Singer on charitable donation.

They’ll say, “What, do you expect epistemologists to have more

knowledge? Do you expect doctors to be

less likely to smoke?” I’ll reply that

the empirical evidence does suggest that doctors are less likely to smoke than

non-doctors of similar social and economic background.[12] Maybe epistemologists don’t have more

knowledge, but I’d hope that specialists in feminism were less biased against

women – and if they weren’t, that would be interesting to know. I’ll suggest that the relationship between

professional specialization and personal life might play out differently for

different professions.

It seems odd to me that philosophers have so little to

say about this matter. We criticize

Martin Heidegger for his Nazism, and we wonder how deeply connected his Nazism

was to his other philosophical views.[13] But we don’t feel the need to turn the mirror

on ourselves.

The same issues arise with clergy. In 2010, I was presenting some of my work at

the Confucius Institute for Scotland.

Afterward, I was approached by not one but two bishops. I asked them whether they thought that

clergy, on average, behaved better, the same, or worse than laypeople.

“About the same,” said one.

“Worse!” said the other.

No clergyperson has ever expressed to me the view that

clergy behave on average better than laypeople, despite all their immersion in

religious teaching and ethical conversation.

Maybe in part this is modesty on behalf of their profession. But in most of their voices, I also hear

something that sounds like genuine disappointment, some remnant of the young

adult who had headed off to seminary hoping it would be otherwise.

#

In a series of empirical studies starting in 2007 –

mostly in collaboration with the philosopher Joshua Rust – I have empirically

explored the moral behavior of ethics professors. As far as I know, Josh and I are the only

people ever to have done so in a systematic way.[14]

Here are the measures we’ve looked at: voting in public

elections, calling one’s mother, eating the meat of mammals, donating to

charity, littering, disruptive chatting and door-slamming during philosophy

presentations, responding to student emails, attending conferences without

paying registration fees, organ donation, blood donation, theft of library

books, overall moral evaluation by one’s departmental peers, honesty in

responding to survey questions, and joining the Nazi party in 1930s Germany.

Obviously, some of these measures are more significant

than others. They range from

trivialities (littering) to substantial life decisions (joining the Nazis), and

from contributions to strangers (blood donation) to personal interactions

(calling Mom). Some of our measures rely

on self-report (we didn’t ask ethicists’ mothers how long it had really been) but in many cases we had

direct observational evidence.

Ethicists do not appear to behave better. Never once have we found ethicists as a whole

behaving better than our comparison groups of other professors, by any of our

main planned measures. But neither,

overall, do they seem to behave worse.

(There are some mixed results for secondary measures and some cases

where it matters who is the comparison group.)

For the most part, ethicists behave no differently from other sorts of

professors – logicians, biologists, historians, foreign-language instructors.

Nonetheless, ethicists do embrace more stringent moral

norms on some issues, especially vegetarianism and charitable donation. Our results on vegetarianism were especially

striking. In a survey of professors from

five U.S. states, we found that 60% of ethicist respondents rated “regularly

eating the meat of mammals, such as beef or pork” somewhere on the “morally

bad” side of a nine-point scale ranging from “very morally bad” to “very

morally good”. In contrast, only 19% of

professors in departments other than philosophy rated it as bad. That’s a pretty big difference of

opinion! Non-ethicist philosophers were

intermediate, at 45%. But when asked

later in the survey whether they had eaten the meat of a mammal at their

previous evening meal, we found no statistically significant difference in the

groups’ responses – 38% of professors reported having done so, including 37% of

ethicists.[15]

Similarly for charitable donation. In the same survey, we asked respondents what

percentage of income, if any, the typical professor should donate to charity,

and then later we asked what percentage of income they personally had given in

the previous calendar year. Ethicists

espoused the most stringent norms: their average recommendation was 7%,

compared with 5% for the other two groups.

However, ethicists did not report having given a greater percentage of

income to charity than the non-philosophers (4% for both groups). Nor did adding a charitable incentive to half

of our surveys (a promise of a $10 donation to their selected charity from a

list) increase ethicists’ likelihood of completing the survey. Interestingly, the non-ethicist philosophers,

though they reported having given the least to charity (3%), were the only

group that responded to our survey at detectably higher rates when given the

charitable incentive.[16]

#

Should we expect ethicists to behave especially

morally well as a result of their training – or at least more in accord with

the moral norms that they themselves espouse?

Maybe we can defend a “no”. Consider this thought experiment:

An ethics professor teaches Peter Singer’s arguments

for vegetarianism to her undergraduates.[17] She says she finds those arguments sound and

that in her view it is morally wrong to eat meat. Class ends, and she goes to the cafeteria for

a cheeseburger. A student approaches her

and expresses surprise at her eating meat.

(If you don’t like vegetarianism as an issue, consider marital fidelity,

charitable donation, fiscal honesty, or courage in defense of the weak.)

“Why are you surprised?” asks our ethicist. “Yes, it is morally wrong for me to enjoy

this delicious cheeseburger. However, I

don’t aspire to be a saint. I aspire

only to be about as morally good as others around me. Look around this cafeteria. Almost everyone is eating meat. Why should I sacrifice this pleasure, wrong

though it is, while others do not?

Indeed, it would be unfair to hold me to higher standards just because

I’m an ethicist. I am paid to teach,

research, and write, like every other professor. I am paid to apply my scholarly talents to

evaluating intellectual arguments about the good and the bad, the right and the

wrong. If you want me also to live as a

role model, you ought to pay me extra!

“Furthermore,” she continues, “if we demand that ethicists

live according to the norms they espouse, that will put major distortive

pressures on the field. An ethicist who

feels obligated to live as she teaches will be motivated to avoid highly

self-sacrificial conclusions, such as that the wealthy should give most of

their money to charity or that we should eat only a restricted subset of

foods. Disconnecting professional

ethicists’ academic inquiries from their personal choices allows them to

consider the arguments in a more even-handed way. If no one expects us to act in accord with

our scholarly opinions, we are more likely to arrive at the moral truth.”

“In that case,” replies the student, “is it morally

okay for me to order a cheeseburger too?”

“No! Weren’t

you listening? It would be wrong. It’s wrong for me, also, as I just

admitted. I recommend the avocado and

sprouts. I hope that Singer’s and my

arguments help create a culture permanently free of the harms to animals and

the environment that are caused by meat-eating.”

“This reminds me of Thomas Jefferson’s attitude toward

slave ownership,” I imagine the student replying. Maybe the student is Black.

“Perhaps so.

Jefferson was a great man. He had

the courage to recognize that his own lifestyle was morally odious. He acknowledged his mediocrity and resisted

the temptation to paper things over with shoddy arguments. Here, have a fry.”

Let’s call this view cheeseburger ethics.

#

Any of us could easily become much morally better than

we are, if we chose to. For those of us

who are affluent by global standards, one path is straightforward: Spend less

on luxuries and give the savings to a good cause. Even if you aren’t affluent by global

standards, unless you are on the precipice of ruin, you could give more of your

time to helping others. It’s not

difficult to see multiple ways, every day, in which one could be kinder to

those who would especially benefit from kindness.

And yet, most of us choose mediocrity instead. It’s not that we try but fail, or that we

have good excuses. We – most of us –

actually aim at mediocrity. The

cheeseburger ethicist is perhaps only unusually honest with herself about

this. We aspire to be about as morally

good as our peers. If others cheat and

get away with it, we want to do the same.

We don’t want to suffer for goodness while others laughingly gather the

benefits of vice. If the morally good

life is uncomfortable and unpleasant, if it involves repeated painful

sacrifices that aren’t compensated in some way, sacrifices that others aren’t

also making, then we don’t want it.

Recent empirical work in moral psychology and

experimental economics, especially by Robert B. Cialdini and Cristina

Bicchieri, seems to confirm this general tendency.[18] People are more likely to comply with norms

that they see others following, less likely to comply with norms when they see

others violating them. Also, empirical

research on “moral self-licensing” suggests that people who act well on one

occasion often use that as an excuse to act less well subsequently.[19] We gaze around us, then aim for so-so.

What, then, is moral reflection good for? Here’s one thought. Maybe it gives us the power to calibrate more

precisely toward our chosen level of mediocrity. I sit on the couch, resting while my wife

cleans up from dinner. I know that it

would be morally better to help than to continue relaxing. But how bad, exactly, would it be for me not

to help? Pretty bad? Only a little bad? Not at all bad, but also not as good as I’d

like to be if I weren’t feeling so lazy?

These are the questions that occupy my mind. In most cases, we already know what is

good. No special effort or skill is

needed to figure that out. Much more

interesting and practical is the question of how far short of the ideal we are

comfortable being.

Suppose it’s generally true that we aim for goodness

only by peer-relative, rather than absolute, standards. What, then, should we expect to be the effect

of discovering, say, that it is morally bad to eat meat, as the majority of

U.S. ethicists seem to think? If you’re

trying to be only about as good as others, and no better, then you can keep

enjoying the cheeseburgers. Your

behavior might not change much at all.

What would change is this: You’d acquire a lower opinion of (almost)

everyone’s behavior, your own included.

You might hope that others will change. You might advocate general social change –

but you’ll have no desire to go first.

Like Jefferson maybe.

#

I was enjoying dinner in an expensive restaurant with

an eminent ethicist, at the end of an ethics conference. I tried these ideas out on him.

“B+,” he said.

“That’s what I’m aiming for.”

I thought, but I didn’t say, B+ sounds good. Maybe that’s

what I’m aiming for too. B+ on the great

moral curve of White middle-class college-educated North Americans. Let others get the As.

Then I thought, most of us who are aiming for B+ will

probably fall well short. You know,

because we fool ourselves. Here I am

away from my children again, at a well-funded conference in a beautiful

$200-a-night hotel, mainly, I suspect, so that I can nurture and enjoy my

rising prestige as a philosopher. What

kind of person am I? What kind of

father? B+?

(Oh, it’s excusable! – I hear myself saying. I’m a model of career success for the kids,

and of independence. And morality isn’t

so demanding. And my philosophical work

is a contribution to the general social good.

And I give, um, well, a little to charity, so that makes up for it. And I’d be too disheartened if I couldn’t do

this kind of thing, which would make me worse as a father and as a teacher of

ethics. Plus, I owe it to myself. And….

Wow, how neatly what I want to do fits with what’s ethically best, once

I think about it! [See Chapter 3 on

Happy Coincidence Reasoning.])

A couple of years later, I emailed that famous

ethicist about the B+ remark, to see if I could quote him on it by name. He didn’t recall having said it, and he

denied that was his view. He is aiming

for moral excellence after all. It must

have been the chardonnay speaking.

#

Most of the ancient philosophers and great moral

visionaries of the religious wisdom traditions, East and West, would find the

cheeseburger ethicist strange. Most of

them assumed that the main purpose of studying ethics was self-improvement. Most of them also accepted that philosophers

were to be judged by their actions as much as by their words. A great philosopher was, or should be, a role

model: a breathing example of a life well-lived. Socrates taught as much by drinking the

hemlock as by any of his dialogues, Confucius by his personal correctness,

Siddhartha Guatama by his renunciation of wealth, Jesus by washing his

disciples’ feet. Socrates does not say:

Ethically, the right thing for me to do would be to drink this hemlock, but I

will flee instead! (Maybe he could have

said that, but then he would have been a different sort of model.)

I’d be suspicious of a 21st-century philosopher who

offered up her- or himself as a model of wise living. This is no longer what it is to be a

philosopher – and those who regard themselves as especially wise are in any

case usually mistaken. Still, I think,

the ancient philosophers got something right that the cheeseburger ethicist

gets wrong.

Maybe it’s this: I have available to me the best

attempts of earlier generations to express their ethical understanding of the

world. I even seem to have some

advantages over ancient philosophers, in that there are now many more centuries

of written texts and several distinct cultures with long traditions that I can

compare. And I am paid, quite handsomely

by global standards, to devote a large portion of my time to thinking through

this material. What should I do with

this amazing opportunity? Use it to get

some publications and earn praise from my peers, plus a higher salary? Sure.

Use it – as my seven-year-old son observed – as a tool to badger others

into treating me better? Okay, I guess

so, sometimes. Use it to try to shape

other people’s behavior in a way that will make the world a generally better

place? Simply enjoy its power and beauty

for its own sake? Yes, those things too.

But also, it seems a waste not to try to use it to

make myself ethically better than I currently am. Part of what I find unnerving about the

cheeseburger ethicist is that she seems so comfortable with her mediocrity, so

uninterested in deploying her philosophical tools toward self-improvement. Presumably, if approached in the right way,

the great traditions of moral philosophy have the potential to help us become

morally better people. In cheeseburger

ethics, that potential is cast aside.

The cheeseburger ethicist risks intellectual failure

as well. Real engagement with a

philosophical doctrine probably requires taking some steps toward living

it. The person who takes, or at least

tries to take, personal steps toward Kantian scrupulous honesty, or Mozian

impartiality, or Buddhist detachment, or Christian compassion, gains a kind of

practical insight into those doctrines that is not easily achieved through

intellectual reflection alone. A

full-bodied understanding of ethics requires some relevant life experience.

What’s more, abstract doctrines lack specific content

if they aren’t tacked down in a range of concrete examples. Consider the doctrine “treat everyone as

equals who are worthy of respect”. What

counts as adhering to this norm, and what constitutes a violation of it? Only when we understand how norms play out

across examples do we really understand them.[20] Living our norms, or trying to live them,

forces a maximally concrete confrontation with examples. Does your ethical vision really require that

you free the slaves on which your lifestyle crucially depends? Does it require giving away your salary and

never again enjoying an expensive dessert?

Does it require drinking hemlock if your fellow citizens unjustly demand

that you do so?

Few professional ethicists really are cheeseburger

ethicists, I think, when they stop to consider it. They – or rather we, I suppose, as I find

myself becoming more and more an ethicist, do want our ethical reflections to

improve us morally, a little bit. But

here’s the catch: We aim only to become a

little morally better. We cut

ourselves slack when we look at others around us. We grade ourselves on a curve and tell

ourselves, if pressed, that we’re aiming for B+ rather than A. And at the same time, we excel at

rationalization and excuse-making – maybe more so, the more ethical theories we

have ready to hand. So we end, on

average, about where we began, behaving more or less the same as others of our

social group.

Should we aim for “A+”, then? Being frank with myself, I don’t want the

self-sacrifice I’m pretty sure would be required. Should I aim at least a little higher than

B+? Should I resolutely aim to be

morally far better than my peers – A or maybe A-minus – even if not quite a

saint? I worry that needing to see

myself as unusually morally excellent is more likely to increase self-deception

and rationalization than to actually improve me.

Should I redouble my efforts to be kinder and more

generous, coupling them with reminders of humility about my likelihood of

success? Yes, I will – today! But I already feel my resentment building,

and I haven’t even done anything yet.

Maybe I can escape that resentment by adjusting my sense of “mediocrity”

upward. I might try to recalibrate by

surrounding myself with like-minded peers in virtue. But avoiding the company of those I deem

morally inferior seems more characteristic of the moralizing jerk than of the

genuinely morally good person.

I can’t quite see my way forward. But now I worry that this, too, is

excuse-making. Nothing will ensure

success, so (phew!) I can comfortably stay in the same old mediocre place I’m

accustomed to. This defeatism also fits

nicely with one natural way to read Josh Rust’s and my data: Since ethicists

don’t behave better or worse than others, philosophical reflection must be

behaviorally inert, taking us only where we were already headed, its power

mainly that of providing different words by which to decorate our pre-determined

choices.[21] So I’m not to be blamed if all my ethical

philosophizing hasn’t improved me.

I reject that view.

Instead I favor this less comfortable idea: Philosophical reflection

does have the power to move us, but it is not a tame thing. It takes us where we don’t intend or expect,

sometimes one way, as often the other, sometimes amplifying our vices and

illusions, sometimes yielding real insight and inspiring substantial moral

change. These tendencies cross-cut and

cancel in complex ways that are difficult to detect empirically. If we could tell in advance which direction

our reflection would carry us and how, we’d be implementing a pre-set

educational technique rather than challenging ourselves philosophically.

Genuine philosophical thinking critiques its prior

strictures, including even the assumption that we ought to be morally

good. It damages almost as often as it

aids, is free, wild, and unpredictable, always breaks its harness. It will take you somewhere, up, down,

sideways – you can’t know in advance.

But you are responsible for trying to go in the right direction with it,

and also for your failure when you don’t get there.

5. On Not Seeking Pleasure Much

Back in the 1990s, when I was a graduate student, my

girlfriend Kim asked me what, of all things, I most enjoyed doing. Skiing, I answered. I was thinking of those moments breathing the

cold, clean air, relishing the mountain view, then carving a steep, lonely

slope. I’d done quite a lot of that with

my mom when I was a teenager. But how

long had it been since I’d gone skiing?

Maybe three years? Grad school

kept me busy and I now had other priorities for my winter breaks. Kim suggested that if it had been three years

since I’d done what I most enjoyed doing, then maybe I wasn’t living wisely.

Well, what, I asked, did she most enjoy? Getting massages, she said. Now, the two of us had a deal at the time: If

one gave the other a massage, the recipient would owe a massage in return the

next day. We exchanged massages

occasionally, but not often, maybe once every few weeks. I pointed out that she, too, might not be

perfectly rational: She could easily get much more of what she most enjoyed

simply by giving me more massages.

Surely the displeasure of massaging my back couldn’t outweigh the

pleasure of the thing she most enjoyed in the world? Or was pleasure for her such a tepid thing

that even the greatest pleasure she knew was hardly worth getting?

Suppose it’s true that avoiding displeasure is much

more motivating than gaining pleasure, so that even our top pleasures (skiing,

massages) aren’t motivationally powerful enough to overcome only moderate

displeasures (organizing a ski trip, giving a massage).[22] Is this rational? Is displeasure more bad than pleasure is

good? Is it much better to have a steady

neutral than a mix of highs and lows? If

so, that might explain why some people are attracted to the Stoics’ and

Buddhists’ emphasis on avoiding suffering, even at the cost of losing

opportunities for pleasure.[23]

Or is it irrational not to weigh pleasure and

displeasure evenly? In dealing with

money, people will typically, and seemingly irrationally, do much more to avoid

a loss than to secure an equivalent gain.[24] Maybe it’s like that? Maybe sacrificing two units of pleasure to

avoid one unit of displeasure is like irrationally forgoing a gain of $2 to

avoid a loss of $1?

It used to be a truism in Western, especially British,

philosophy that people sought pleasure and avoided pain. A few old-school psychological hedonists,

like Jeremy Bentham, went so far as to say that was all that motivated us.[25] I’d guess quite differently: Although pain is

moderately motivating, pleasure motivates us very little. What motivates us more are outward goals,

especially socially approved goals – raising a family, building a career,

winning the approval of peers – and we will suffer immensely for these

things. Pleasure might bubble up as we

progress toward these goals, but that’s a bonus and side-effect, not the

motivating purpose, and summed across the whole, the displeasure might vastly

outweigh the pleasure. Evidence suggests

that even raising a child is probably for most people a hedonic net negative,

adding stress, sleep deprivation, and unpleasant chores, as well as crowding

out the pleasures that childless adults regularly enjoy.[26]

Have you ever watched a teenager play a challenging

video game? Frustration, failure,

frustration, failure, slapping the console, grimacing, swearing, more

frustration, more failure – then finally, woo-hoo! The sum over time has got to be negative; yet

they’re back again to play the next game.

For most of us, biological drives and addictions, personal or socially

approved goals, concern for loved ones, habits and obligations – all appear to

be better motivators than gaining pleasure, which we mostly seem to save for

the little bit of free time left over.

If maximizing pleasure is central to living well and

improving the world, we’re going about it entirely the wrong way. Do you really want to maximize pleasure? I doubt it.

Me, I’d rather write some good philosophy and raise my kids.

6. How Much Should You Care about How You Feel in Your Dreams?

Prudential hedonists say that how well your life

is going for you, your personal well-being, is wholly constituted by facts

about how much pleasure or enjoyment you experience and how much pain,

displeasure, or suffering you experience.

(This is different from motivational

hedonism, discussed in Chapter 5, which concerns what moves us to act.) Prudential hedonism is probably a minority

view among professional philosophers: Most would say that personal well-being

is also partly constituted by facts about your flourishing or the attainment of

things that matter to you – good health, creative achievement, loving

relationships – even if that flourishing or attainment isn’t fully reflected in

positive emotional experiences.[27] Nevertheless, prudential hedonism might seem

to be an important part of the story:

Improving the ratio of pleasure to displeasure in life might be central to

living wisely and structuring a good society.

Often a dream is the most pleasant or unpleasant thing

that occurs all day. Discovering that

you can fly – whee! How much do you do

in waking life that is as fun as that? Conversely,

how many things in waking life are as unpleasant as a nightmare? Most of your day you ride on an even keel,

with some ups and downs; but at night your dreams bristle with thrills and

anguish.

Here’s a great opportunity, then, to advance the

hedonistic project! Whatever you can do

to improve the ratio of pleasant to unpleasant dreams should have a big impact

on the ratio of pleasure to displeasure in your life.

This fact explains the emphasis prudential hedonists

and utilitarian ethicists have placed on improving one’s dream life. It also explains the gargantuan profits of

all those dream-improvement mega-corporations.

Not. Of course

not! When I ask people how concerned

they are about the overall hedonic balance of their dreams, their response is

almost always a shrug. But if the

overall sum of felt pleasure and displeasure is important, shouldn’t we take at

least somewhat seriously the quality of our dream lives?

Dreams are usually forgotten, but I’m not sure how

much that matters. Most people forget

most of their childhood, and within a week they forget almost everything that

happened on a given day. That doesn’t make

the hedonic quality of those events irrelevant.

Your two-year-old might entirely forget the birthday party a year later,

but you still want her to enjoy it, right?

And anyway, we can work to remember our dreams if we want. Simply attempting to remember one’s dreams

upon waking, by jotting some notes into a dream diary, dramatically increases

dream recall.[28] So if recall were important, you could work toward

improving the hedonic quality of your dreams (maybe by learning lucid dreaming?[29]) and also work to improve

your dream memory. The total impact on

the amount of remembered pleasure in your life could be enormous!

I can’t decide whether the fact that I haven’t acted

on this sensible advice illustrates my irrationality or instead illustrates

that I care even less about pleasure and displeasure than I said in Chapter 5.[30]

7. Imagining Yourself in Another’s Shoes vs. Extending Your Love

There’s something I don’t like about the “Golden

Rule”, the admonition to do unto others as you would have others do unto you.

Consider this passage from the ancient Chinese philosopher

Mengzi (Mencius):

That which people are

capable of without learning is their genuine capability. That which they know without pondering is

their genuine knowledge. Among babes in

arms there are none that do not know to love their parents. When they grow older, there are none that do

not know to revere their elder brothers.

Treating one’s parents as parents is benevolence. Revering one’s elders is righteousness. There is nothing else to do but extend these

to the world.[31]

One thing I like about the

passage is that it assumes love and reverence for one’s family as a given,

rather than as a special achievement. It

portrays moral development simply as a matter of extending that natural love

and reverence more widely.

In another famous passage, Mengzi notes the kindness

that the vicious tyrant King Xuan exhibits in saving a frightened ox from

slaughter, and he urges the king to extend similar kindness to the people of

his kingdom.[32] Such extension, Mengzi says, is a matter of

“weighing” things correctly – a matter of treating similar things similarly and

not overvaluing what merely happens to be nearby. If you have pity for an innocent ox being led

to slaughter, you ought to have similar pity for the innocent people dying in

your streets and on your battlefields, despite their invisibility beyond your

beautiful palace walls.

The Golden Rule works differently – and so too the

common advice to imagine yourself in someone else’s shoes. Golden Rule / others’ shoes advice assumes

self-interest as the starting point, and implicitly treats overcoming egoistic

selfishness as the main cognitive and moral challenge.

This contrasts sharply with Mengzian extension, which

starts from the assumption that you are already concerned about nearby others,

and takes the challenge to be extending that concern beyond a narrow circle.

Maybe we can model Golden Rule / others’ shoes

thinking like this:

(1.) If I were in the

situation of Person X, I would want to be treated according to Principle P.

(2.) Golden Rule: Do unto

others as you would have others do unto you.

(3.) Thus, I will treat

Person X according to Principle P.

And maybe we can model

Mengzian extension like this:

(1.) I care about Person Y

and want to treat them according to Principle P.

(2.) Person X, though

perhaps more distant, is relevantly similar.

(3.) Thus, I will treat

Person X according to Principle P.

There will be other more

careful and detailed formulations, but this sketch captures the central

difference between these two approaches to moral cognition. Mengzian extension models general moral

concern on the natural concern we already have for people close to us, while

the Golden Rule models general moral concern on concern for oneself.

I like Mengzian extension better for three reasons.

First, Mengzian extension is more psychologically

plausible as a model of moral development.

People do, naturally, have concern and compassion for others around

them. Explicit exhortations aren’t

needed to produce this. This natural

concern and compassion is likely to be the main seed from which mature moral

cognition grows. Our moral reactions to

vivid, nearby cases become the bases for more general principles and

policies. If you need to reason or

analogize your way into concern even for close family members, you’re already

in deep moral trouble.

Second, Mengzian extension is less ambitious – in a

good way. The Golden Rule imagines a

leap from self-interest to generalized good treatment of others. This may be excellent and helpful advice,

perhaps especially for people who are already concerned about others and

thinking about how to implement that concern.

But Mengzian extension has the advantage of starting the cognitive

project much nearer the target, requiring less of a leap. Self to other is a huge moral and ontological

divide. Family to neighbor, neighbor to

fellow citizen – that’s much less of a divide.

Third, Mengzian extension can be turned back on

yourself, if you are one of those people who has trouble standing up for your

own interests – if you are, perhaps, too much of a sweetheart (in the sense of

Chapter 1). You would want to stand up

for your loved ones and help them flourish.

Apply Mengzian extension, and offer the same kindness to yourself. If you’d want your father to be able to take

a vacation, realize that you probably deserve a vacation too. If you wouldn’t want your sister to be

insulted by her spouse in public, realize that you too shouldn’t have to suffer

that indignity.[33]

Although Mengzi and the 18th-century French

philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau both endorse mottoes standardly translated as

“human nature is good” and have views that are similar in important ways,[34] this is one difference

between them. In both Emile and Discourse on Inequality, Rousseau emphasizes self-concern as the

root of moral development, making pity and compassion for others secondary and

derivative. He endorses the foundational

importance of the Golden Rule, concluding that “Love of men derived from love

of self is the principle of human justice”.[35]

This difference between Mengzi and Rousseau is not a

general difference between East and West.

Confucius, for example, endorses something like the Golden Rule: “Do not

impose on others what you yourself do not desire”.[36] Mozi and Xunzi, also writing in the period,

imagine people acting mostly or entirely selfishly, until society artificially

imposes its regulations, and so they see

the enforcement of rules rather than Mengzian extension as the foundation of

moral development.[37] Moral extension is thus specifically Mengzian

rather than generally Chinese.

Care about me not because you can imagine what you

would selfishly want if you were me.

Care about me because you see how I am not really so different from

others you already love.

8. Is It Perfectly Fine to Aim for Moral Mediocrity?

As I suggested in Chapter 4, as well as in other work,[38] most people aim to be

morally mediocre. They aim to be about

as morally good as their peers, not especially better, not especially

worse. They don’t want to be the one

honest person in a classroom of unpunished cheaters; they don’t want to be the

only one of five housemates who reliably cleans up her messes and returns what

she borrows; they don’t want to turn off the air conditioner and let the lawn

die to conserve energy and water if their neighbors aren’t doing the same. But neither do most people want to be the

worst sinner around – the most obnoxious of the housemates, the lone cheater in

a class of honorable students, the most wasteful homeowner on the block.

Suppose I’m right about that. What is the ethics of aiming for moral

mediocrity? It kind of sounds bad, the

way I put it – aiming for mediocrity.

But maybe it’s not so bad, really?

Maybe there’s nothing wrong with aiming for the moral middle. “Cs get degrees!” Why not just go for a low pass – just enough

to squeak over the line, if we’re grading on a curve, while simultaneously

enjoying the benefits of moderate, commonplace levels of deception,

irresponsibility, screwing people over, and destroying the world’s resources

for your favorite frivolous luxuries?

Maybe that’s good enough, really, and we should save our negative

judgments for what’s more uncommonly rotten.[39]

There are two ways you could argue that it’s not bad